|

This post is a departure from our usual blog format of short pieces about research and practice in our group: it's a personal reflection (from Winnifred Louis) on Donald Taylor as a person, and his scholarship and influence.

I was a masters student with Don starting in 1994, when I wrote a thesis on reactions to gender discrimination at McGill University. I then went on to complete my PhD with him from 1996, looking at reactions to English-French conflict in Quebec. He generously involved me in projects and papers on attitudes to immigrants in South Africa and heritage language retention in Quebec, and we worked together on a paper on responses to 9/11, and then on responses to terrorism. After I graduated, he cheered me on and welcomed my students’ visits. He passed away from cancer last month, in November 2021. I can’t possibly express how much I love the guy and what he meant to me, but here is a short list of some of the key things that come to mind. Autonomous students. Like all Don’s students I worked on projects close to my heart and my interests, I didn’t build an empire for him. He used to laugh at people who would take credit for their students’ work and say, “good supervision is when you set it up for students to steal *your* ideas!”. Students would come in rambling and riffing, and he’d point them to the relevant literatures and send them off to forage, then when they came back, distill their chaotic learnings into hypotheses and a sound research design, and loop them to repeat, as they developed “their” project. Don loved the diverse research that this approach brought to him. And when the PhD students finished, he set them up to develop new collaborations, so they could establish themselves as independent scholars, instead of milking their PhD, not matter how successful it was. “If I couldn’t totally change my research focus every seven years I wouldn’t be here,” he said. Incredible hulk. Don was a guy who was broad-shouldered and beefy, a football and hockey player at the varsity level. His fashion sense was erratic - in our first meetings, I was alarmed by his 70s style, with shirt open to mid chest, and gold chains nestling in his chest hair. I thought this must mean he was terribly sexist – and some of his unsavory comments didn’t help allay that fear, talking about how the girls chased the players on varsity teams, or how he and a friend in grad school had planned to start a university so they could fool around with the undergrad girls. He used to wear an Australian Akubra cowboy hat and oilskins - he liked the look - and signed an email to me in 2020 with a smiling emoji wearing a cowboy hat. Even in our last ftf meeting, when he was in his late 70s, he turned up in his Akubra, and told me with glee how he’d been captured by the cult of cross-fit, referring to himself as a gym-jockey. But what I quickly learned was that for all this flamboyance - he loved attention, he loved sports, he loved physical challenges – Don was very far from the stereotypes of toxic masculinity, insensitive or domineering. Instead, he was a gentle and often a humble person. The more shy and powerless the other person, the more Don was respectful and kind, quick to self-deprecate or joke, hunching down and tilting his head, attentively listening and learning. Support for square pegs. The transition from football scholarship to academic research saw Don scrape over class barriers that were very much alive in the 1950s and 1960s. Maybe that was why he was always ready to support square pegs to work their way into the system. Anyone who battled their way through was liable to find him ready to hold the door open into his lab – female students, or people from minority ethnic groups, at times when that was still unusual at McGill. Refugees from Iran and Rwanda. Myself as a lesbian, at a time when I didn’t know anyone at all, in all of academic psychology, who was openly gay. Quirky characters with narrow focus, and people raging against the system. He savoured the diversity and the joyfulness of people whooshing out the doors of his lab with skills and drive. “You’ve got to launch them!,” he said to me on mentoring grad students. “You don’t just churn them out, you launch them!” Passion for teaching. At the same time Don loved and respected undergraduate teaching. Famously he never missed a class in his 40+ years of undergrad teaching, even the day after a hockey game where he had 20 stitches to his face. “You will influence many more people through your teaching than through your research,” he used to say to me and others. He would teach huge classes of 700, but always remembered to see the students as individual people. He would discard the scheduled lecture content to respond to climactic events, like 9/11. He would talk to students and he would listen to them. I used to fear public speaking tremendously myself, to the point of blushing, trembling, and cracking voice, complete overwhelm. “You feel fear as a teacher when you are thinking about yourself,” he said to me kindly. “Try to think about your students instead - how much you want them to learn what you’re saying. Think about the content, and how much you love the content, and why you care!” Good advice - he was an excellent public speaker. “You’ve got to live for the anecdote!,” he used to say. Don was also a story-teller who would mercilessly blow the time limits of his talks, and of his classes, in order to digress to stories that made people laugh, think and act differently. But he was also someone who, in his everyday life and his career, would turn to go down less travelled paths, stop to hear from unexpected people, and choose something strange and different whenever the choice was offered. “Live for the anecdote!,” he would say. Don’t get stuck in a rut. Don’t pass by the opportunity that won’t come again. Live with panache! Make a difference! Don’s career was impressive in many respects, but perhaps most unusual in showing his long-term commitment to sweeping social change around the world. For five years as a PhD student, I flew up annually on seven-seater planes to Kangiqsujuaq, a tiny village in Arctic Quebec, 100s of kilometers above the treeline. I was part of a 30 year rotating team of students and RAs who learned about the North and contributed to research co-designed with Indigenous Inuit communities on language, identity, and social attitudes. Another time, with Don, I contributed to a special issue in memory of William Robinson, a language scholar who was retiring, and who lamented that at the close of his career he was disappointed that he had not overthrown the class system in the UK. Don and I laughed – but Don applauded that he had never lowered his sights. “They just don’t get it!,” Don used to say irritably, skimming the latest incremental, trivial study, or self-focused theoretical micro-dispute. The world was full of huge problems, with real people struggling - *these* problems needed attention and theorising. The big problems, the big picture – his students were always pushed to consider how our research fit into these categories. Moving beyond the WEIRD context before it was labelled as such, Don introduced me and dozens of other students and collaborators to challenges facing disadvantaged communities, and encouraged us to study them – by going there, by being there, by listening, by working with them, by following their agendas. He supported scholars from the disadvantaged communities and in the global south, and amplified their voices and their theorising. Pragmatism and sober-minded clarity. He was woke before there was wokeness, but at the same time, he would never have presumed that others would feel the same way, or waste time being surprised if others rejected those values. Don was always really clear about the academia that we worked in as not valuing social change or positive benefits to communities, and even being hostile to them. Maybe that’s not true now in some cases – I hope so. But I still teach my students what Don taught me in the 1990s. He said, you need two lines of research: a mainstream one using mainstream methods published in mainstream journals – this will get you your job, tenure and promotion. It will get you grants. The other work, your applied work, you have to be ready to have dismissed. It has to be for the benefit of communities, so it may be slower, or grind to a halt, or blow apart due to politics. Maybe there will be no academic outcomes for years, or at all. Publication may be relegated to journals and conferences that powerful gatekeepers don’t care about at all, or even see as harmful. (In my own career, a former Head of School, which is like a department chair, once remarked, “If you’re going to publish in the Journal of Applied Social Psychology, why publish at all?”) So you have to do both mainstream and applied work, to secure your future, Don would say. You have to publish. But it’s not *just* about job security. Applied work will make you a better theoretician, Don said – more alive to complexity, more aware of received wisdom that’s not actually true. Go outside the box. Look back from the outside. And also: theorising and experiments will strengthen your contribution to application – they will help to untangle causality. And they will credential you to go out to communities and speak to policy makers. Money matters. In the same pragmatic vein, Don was always keenly aware that money matters. He learned from Wally Lambert, a social psychologist at McGill famous for his research and his own memorable stories of cheap-skatedness, to never stay at conference hotels, as being too expensive and a ripoff to the taxpayer. Over the course of his career, Don used to reflect with smugness, he’d directed thousands of dollars from his grants towards research participants and RAs, by staying in shared rooms at hostels when he travelled, or with friends, instead of living it up in luxury. He loved the vibe as well – or at least, male graduate students and RAs that’d shared with him brought back stories of Don sitting around in his boxers playing the guitar, and late nights talking theory and drinking beer. More nefariously, in his later career Don used to sneak into conferences to give his research talks without paying to register for them – something that puzzled and exasperated the conference organising teams, often made up of his former students and friends. “These are ridiculously expensive,” he said at one point when I asked him about it - I guess he decided other student and research expenses were more worthy. It’s a choice he felt was legitimate for him to make, which tells you a lot about him. Bend the rules and make them work for you. Don understood the importance of institutions, and cultivated relationships with policy-makers for immigration, language, and race relations carefully all his career. He also kept a vigilant eye on university politics. But he despised bureaucracy and institutional politicking. So he was always ready to bend the rules. He helped set up courses at McGill for Inuttitut education that effectively became offered in intensives, creating a path that allowed Inuit students to credential themselves as teachers with less difficulty. “What kind of names are these?,” the Dean asked him in bewilderment at one point, peering at the -iaq and -miq graduands – unexpected lists of names ending in q and k. Don used to laugh happily to us as he recalled getting the system to work for the students this way. Look for ways to make what you want to do fit a label the system can live with. Look the authorities in the eye and smile blandly. Hold the door open to let others through. Human at work. All of these things influenced me, and they help me now, and my students too, but the thing that speaks most loudly to my heart now is that long before the term was fashionable, Don was ‘human at work’ – he was authentic and real, and not just defined by his job. He spoke to us about his family, and he asked about mine. He came to my wedding. He played music, and sports, and coached kids’ sports, and took time off for holidays with his wife and kids – and he encouraged us to do the same: take time off for other things. Be real. Have friends and family. “It’s different now,” we used to say to him – we grad students of the 1990s – “it’s too competitive, you’ve got to work all the time and stack up publications, you can’t get by and take weekends off”. “I worry that’s true,” he used to say. But work expands to fill the time you give it. Have the best career you can, within the boundaries you set. Don had a great career. He won national awards for teaching, for research, and for service. He was also deeply loved, as much as anyone else I know or more so. At a symposium we had in honour of Don at the Canadian Psychological Association conference in 2016, people came from all over the world to celebrate his influence and research. I came myself from Australia. He was utterly astonished – he was completely flabbergasted that so many people would go to so much effort to celebrate him and his work. I will close this tribute, as I closed the talk on the day, with these words: Thank you Don! For tremendous support personally & professionally for more than 20 years …For an inspiring vision of a great life filled with joyful curiosity, research, family, sports, music, and activism …For moral indignation always translated with determination and humour into action and alliances, …For boundless scepticism about authorities and bureaucracy, but tremendous faith in teaching, science, and possibilities, … And for highlighting the value of living for the anecdote ! *** Other tributes to Don for those who knew him or are curious: In his own words

Others’ words

12 Comments

This blog post aims to summarise the 12 tips provided for early career scholars on having policy impact on our policy page. That page distils the genius of three impactful social psychologists and includes links to lengthy interviews with them on a range of topics. The featured researchers are: community and clinical psychologist Eleanor Wertheim (LaTrobe university), environmental psychologist Kelly Fielding (University of Queensland), and cross-cultural psychologist James Liu (Massey University). The short version is: 1. Join Networks and Teams A central point that all three scholars made is not to imagine you can do it alone - teams are more impactful. Try to find people with like-minded passions, and try to find people with an established track record as mentors, Eleanor Wertheim advises. In general, international collaborations are more impactful. James Liu adds: seek to be part of a team or system – e.g., look for internships – you can't be out there alone. In an ideal world you might even consider policy networking before you choose your PhD advisor. Have they a record of making a difference, of disseminating research? Don't just look for publications. But even if your PhD research ends up as part of a narrower discovery-oriented vision, you can also start to look around for additional role models and mentors during your PhD and as an Early Career Researcher. Opportunities come up to join networks and teams on professional e-lists and as you start to make yourself known at conferences and through publications. A critical point is that if you see an invitation to a meeting, as Kelly Fielding advises, turn up! Go to the meetings, sit down, be friendly, be open, and be excited - show enthusiasm. This is how you signal to others that you are a like-minded person that could be part of an ongoing network. 2. Plan and Learn A closely related point is that like “doing great research”, “having policy impact” requires planning and lots of acquired skills and knowledge. Think about what difference you want to make in the world - aside from career and reputation, what difference will you make? If you already know a general area you want to contribute to, plan for this. Research and join organisations and interest groups. You should also be aware of who is working in the field and approach them to introduce yourself and explain your interests. Think of being in a global network: follow people on Twitter, follow them on google scholar, and join the e-lists of the major NGOs and Institutes that work on the issues you care about. 3. Seize opportunities While research has a long term horizon and discovery (blue sky) research is slow, policy changes happen in fits and starts. Often opportunities only open for change in a country for a window or moment. You will need to learn from your mentors what the state of play is in your area, and what part of the policy cycle people are in. It is a lot easier to spot chances for leverage or learn about needs as part of a network than on your own. Relatedly, you will need to look not just at what you’re interested in, but what government and funding bodies and inquiries and policy-makers are interested in. Think of how you can find common ground. But don’t just think alone – as James Liu says, get advice from your mentors about how to position your research. You will want to practice with mentors how to frame a pitch in terms of what you can bring to particular industry, NGO, or government audiences. Do more Policy impact is not a metric that feeds into getting a job in academia, and it doesn’t help you to get promoted or tenured. It is possible that a policy focus during your PhD could help you to get a job in industry or government, but seek advice if this is your aim – often times that type of job is few and far between. Winnifred Louis advises, to reduce risks in your academic career, you might aim for one line of work that is more predictable, mainstream, and published using methods other high status people in your department/ discipline recognise and value, and in journals people recognise and value. Ticking the boxes in that mainstream area allows you to take on policy work, which has uncertain timelines, controversial topics, mixed methods or under-valued methods, and may go to under-valued journals, or be disseminated in totally different formats (e.g., like websites or workshops) that others discount or see as ‘unscientific’. So, with that caveat in mind, if you’re interested in policy work, ignore the advice to focus narrowly during your PhD. That advice is designed to make sure you get publications and finish, but you will take responsibility to do the former while also jumping at the chance to work with people from different disciplines and outside of academia. Seek to develop pluralistic methods – learn both qualitative and quantitative approaches, etc.. Dealing with conflict and negative feedback Search for impact can bring you into contact with difficult personalities, and into arenas of passionate, bitter conflict between parties with different interests and values. There is no easy solution to this, but you can seek to become self-reflective about your own interests and values, and to upskill on conflict and change for individuals, groups, and societies. Another important point is that much like research and academia in general, in policy work you generally encounter a very high rate of negative feedback. This is especially true early on in your career. You’ll want to practice getting used to the heat of the kitchen – people telling you what you are doing wrong is not a sign that you are failing, it’s a sign that you’re doing challenging work that not everyone values or understands, plus you have a steep learning curve to climb. Mentoring and peer support can help to get over the heavy ground when it all seems too much. Manage your expectations and sustain your motivation A related point is that policy changes happen in fits and starts, and like research, a lot of projects fizzle and fail. So go in with low expectations – outreach increases your chance of impact, but there are no guarantees. James Liu adds, it’s important to understand that you can't control a situation when you are out there in the field – the rigor of the research can be compromised, but this may open you up for insight. You have to be flexible, and be responsive to community needs. Community-engaged and policy-relevant research rarely goes as you planned. It’s a great adventure that keeps you growing as a person. In summary, advice to keep your motivation during times of crushing disappointment includes having a long-term focus, sharing social support with like-minded people, having a growth mindset where you focus on learning and progress not outcomes alone, and having a values mindset where your focus is on how you can do what you can to enact your values with the opportunities that are available. And finally, recognising with humility that there are many factors that you do not control: you’ll need this skill repeatedly, and it will greatly improve your well-being. - By Winnifred Louis Incidents of racial discrimination are all too common, but only recently have such incidents been highly publicized and shared widely on social media. Here are some examples:

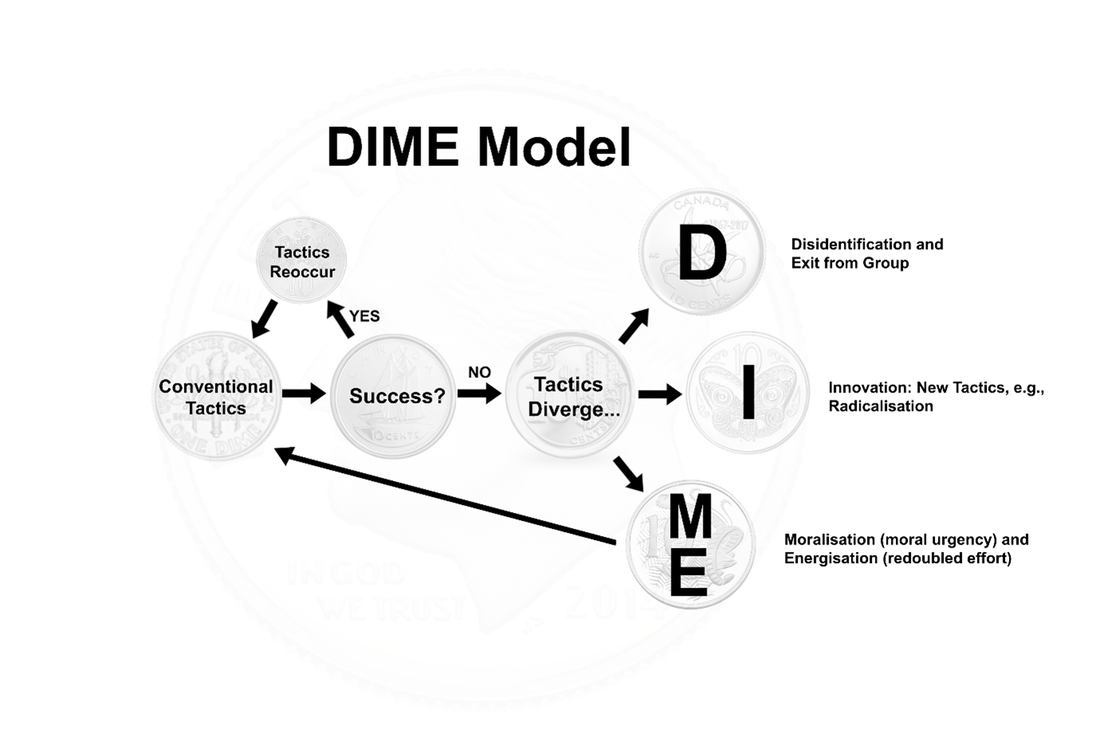

Being largely unaware of the pervasive discrimination faced by Black people and other minoritized groups in the U.S., White people have had often felt little need to do anything about it. Indeed, only a small proportion of White Americans have protested for racial justice, and those who do take action typically report close ties with people from racial and ethnic minority groups. But as millions witnessed the brutal killing of George Floyd while in police custody, we have seen more White people taking to the streets than ever before to protest for racial justice. Thanks in part to social media, White people are beginning to recognize everyday racial profiling and the severity of racial discrimination, and as a result, they are becoming more aware of the White privilege they enjoy. We surveyed nearly 600 White Americans to ask how often they have witnessed an incident of racial discrimination targeting Black people in their day-to-day lives—for example, a Black person being treated differently than other people would be treated at restaurants or stores. We also asked about their awareness of racial privilege and their willingness to take action for racial justice and equality, such as protesting on the streets and attending meetings related to Black Lives Matter protests. Whites’ reported willingness to take action for racial justice was quite low. But the more frequently White people witnessed racial discrimination, the more willing they said they were to take action against racial injustice—and this effect was largely due to their greater awareness of racial privilege. In our next study, we focused on White people who described themselves as “allies” in the pursuit of racial justice, and who had previously taken at least some action to promote racial justice. Once again, we found the more frequently White people witnessed racial discrimination targeting Black people, the more they became aware of racial privilege, and this, in turn, predicted their greater willingness to take action against racial injustice. We next tested experimentally whether exposure to incidents of racial discrimination would lead White Americans to become more aware of racial privilege and more willing to protest for racial justice. Half the participants viewed videos depicting well-publicized incidents of racial discrimination such as described earlier, while the other half viewed only neutral images. Results showed that White participants who viewed the discriminatory incidents reported greater awareness of racial privilege and tended to become more motivated to take action for racial justice. It thus seems that greater awareness of racial privilege can grow from witnessing incidents of racial discrimination indirectly, such as through videos on social media and news reports, without being personally present at such events. These results offer hope that further steps toward racial justice may be taken as White people become more aware of both racial discrimination and their own racial privilege—and, in turn, become more motivated to take action against racial injustice. - By Özden Melis Uluğ & Linda R. Tropp Özden Melis Uluğ is a lecturer in the School of Psychology at the University of Sussex. Linda R. Tropp is a professor of social psychology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. This post is previously published on the Society of Personality and Social Psychology; Character and Context Blog For Further Reading Case, K. A. (2012). Discovering the privilege of whiteness: White women’s reflections on anti-racist identity and ally behavior. Journal of Social Issues, 68(1), 78–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2011.01737.x Tropp, L. R., & Uluğ, Ö. M. (2019). Are White women showing up for racial justice? Intergroup contact, closeness to people targeted by prejudice, and collective action. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 43(3), 335-347. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684319840269 Uluğ, Ö. M., & Tropp, L. R. (2020). Witnessing racial discrimination shapes collective action for racial justice: Enhancing awareness of privilege among advantaged groups. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12731 Collective action is a key process through which people try to achieve social change (e.g., School Strike 4 Climate, Black Lives Matter) or to defend the status quo. Members of social movements use a range of conventional tactics (like petitions and rallies) and radical tactics (like blockades and violence) in pursuit of their goals. In this blog post, we’re writing to introduce DIME, which seeks to model activists’ divergence in tactics. The theoretical model is published in an article on “The volatility of collective action: Theoretical analysis and empirical data”, published online here in Advances in Political Psychology. The model is named after a dime, which is a small ten cent coin in some Western currencies. In English the expressions to “stop on a dime” and “turn on a dime” both communicate an abrupt change of direction or speed. With the DIME model (Figure 1; adapted from Louis et al., 2020, p. 60), our goal was to consider the volatility of collective action, and to put forward the idea that failure diversifies social movements because the collective actors diverge onto distinct and mutually contradictory trajectories. Specifically, the DIME model proposes that after success collective actors generally persist in the original tactics. After failure, however, some actors would Disidentify (losing commitment and ultimately leaving a group). Others would seek to Innovate, leading to trajectories away from the failing tactics that could include radicalisation and deradicalisation. And a third group might double down on their pre-existing attitudes and actions, showing Moralisation, greater moral urgency and conviction, and Energisation, a desire to ramp up the pace and intensity of the existing tactics. We think these responses can all co-occur, but since they are to some extent contradictory (particularly disidentification and moralization/energization), the patterns are often masked within any one sample. They can be teased apart using person-centered analyses that look for groups of respondents with different associations among variables. Another approach could be comparing different types of participants (like people who are more and less committed to a cause) where based on past work we would expect that all three of the responses might emerge as distinct. The disidentification trajectory – getting demotivated and dropping out – has been understudied in collective action, and for groups more broadly (but see Blackwood & Louis, 2012; Becker & Tausch, 2014). A major task for leaders and committed activists is to try to reduce the likelihood of others’ disidentification by creating narratives that sustain commitment to the group in the face of failure. Inexperienced activists, those with high expectations of efficacy, and those with lower levels of identification with the cause may all be more likely to follow a disidentification or exit path. Some that drop out, furthermore, may develop hostility towards the cause they left behind. A challenge for the movement therefore is to manage the bitterness and burnout of former members. The moralization/energization path is likely to be the default path for those who were more committed to the group. In the face of obstacles, these group members will ramp up their commitment. But for how long? Attributions regarding the reason for the failure of the initial action are likely to influence the duration of persistence, we suspect: those with beliefs that the movement can grow and would be more effective if it grew may stay committed for a longer time, for example. In contrast, attributions that failures are due to decision-makers’ corruption or opponents’ intractability may lay the groundwork for taking an innovation pathway. A challenge for the leadership and movement is to understand the reasons for the movement failures as they occur, and to communicate accurate and motivating theories of change that sustain mobilisation. Finally, the innovation path as we conceive it may lead from conventional to radical action (radicalisation), or from radical back to conventional (deradicalisation). It may also lead away from political action altogether, towards more internally focused solidarity and support for ingroup members, or towards movements of creative truth-telling and art. There may be individual difference factors that promote this pathway, but it is also a direction where leadership and contestation of the group’s norms would normally take place, as group members dispute whether the innovation is called for and what new forms of action the group should support. The DIME model aims to answer the call to theorise about the volatility of collective action and the dynamic changes that so clearly occur. It also contributes to a growing body of work that is exploring the nature of radicalisation and deradicalisation. We look forward to engaging with other scholars who have a vision of work in this space. - By Professor Winnifred Louis The Amazon is the largest and most biodiverse tract of tropical rainforest in the world, home to roughly 10% of the world species. It’s also the world’s largest terrestrial carbon dioxide sink and plays a significant role in mitigating global warming. While forest fires in this region are frequent occurrences, and typically happen in dry seasons due to illegal slash-and-burn methods that are used to clear forest for agriculture, livestock, logging and mining, the 2019 wildfires season was particularly devastating. In 2019 alone, estimates suggest over 10 000 km2 of forest within the Amazon biome was lost to the fires with August fires reaching record levels. Destruction of the Amazon doesn’t just threaten increasingly endangered species and the local indigenous populations. As the amount of carbon stored in the Amazon is 70 times greater than the annual US output of greenhouse gases, releasing that amount of extra carbon into the atmosphere would undo everything society has been doing to reduce emissions. Deforestation of the Amazon fluctuates alongside the political landscape of Brazil. Between 1970 and 2005, almost one-fifth of the Brazilian Amazon was deforested. In the 2000s, President Lula da Silva implemented programs to control deforestation, which reduced deforestation by 80% by 2012. Jair Bolsonaro took office in 2019, scaling back the Amazon protections and regulations in hope of stimulating economic growth, which led to a 30% increase in deforestation over the previous year. The international community was understandably displeased; verbal condemnations were made and aid payments to Brazil were cut. However, for the poor populations living in and around the Amazon, it’s about survival. Clearing land gives an immediate economic benefit in the form of cattle ranching, even if it’s an inefficient place to farm cattle due to its distance from potential markets and poor soil quality. If money is the driver of deforestation, perhaps money will offer the solution. The landholders in Brazil could be compensated to forego the profits from converting forests to cattle. There are precedents for such environmental programs, a notable example was China’s Grain for Green program in 1999 – the world’s biggest reforestation program – in which120 million households were paid what amounted to about $150 billion over a decade to protect existing forest or restore forest. In 1996, the Costa Rica government introduced the Payments for Environmental Service (PES) to pay landowners to protect or restore rainforest on their property. With a payment of $50 per hectare, it was enough to slow and reverse deforestation rates. By 2005, Costa Rica’s forest cover has increased by 42% from when the program began. Brazil is also warming up to this idea. One such initiative is the “Adopt a Park” program, announced last month in Brazil, which will allow national and international funds, banks and companies to pay to preserve areas equivalent to 15% of Brazil’s portion of the Amazon – an area larger than Chile. However, for such programs to succeed and attract international support, the Brazilian government would need to demonstrate their ability to stop illegal loggers and wildcat miners from decimating the landscape.

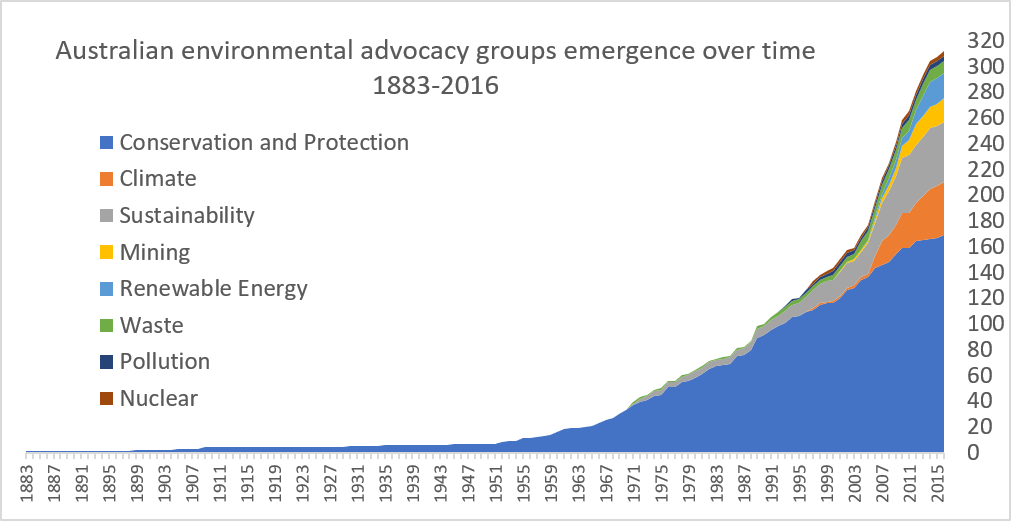

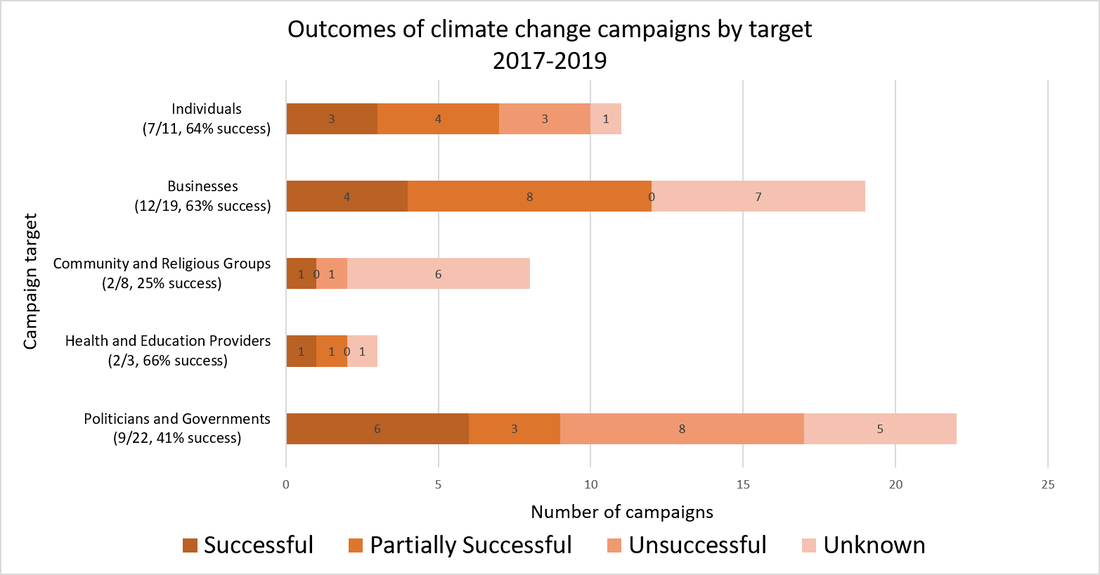

There already exists an appetite for these conservation schemes among world leaders. Norway was willing to provide roughly $100 million per year over a decade to support a non-profit dedicated to reducing Amazon deforestation. In a debate with Bernie Sanders, Joe Biden, the Democratic nominee for president expressed similar sentiment: I would be right now organizing the hemisphere and the world to provide $20 billion for the Amazon, for Brazil no longer to burn the Amazon. These cash-for-conservation schemes might seem like handouts, but it is high time the world’s biggest polluters pay their dues. The Western bloc is responsible for around half of the global historical emissions (the US – 25%, the EU – 22%). Those who will suffer the most acutely from the consequences of climate change are also the least responsible – the poorest of the poor and those living in island states: around 1 billion people in 100 countries. There is a significant ecological debt owed to low-income nations from industrialized first-world nations for the disproportionate emissions of greenhouse gases. Now that the impacts of climate change are unavoidable and worsening, investment in adaptation to rising temperatures and extreme weather is more important than ever. In the drive to better humankind and amass wealth for a few, we’ve wreaked havoc on the world’s environment and put the lives and livelihoods of many in jeopardy. Now it is time for those of us in the West to use our plenitude of wealth, knowledge and technology to help those in need, and to mitigate and prepare for the consequences of our actions. From reduced air pollution to cleaner water, the COVID-19 pandemic has provided a vision of hope: evidence that we are capable of rapidly changing our behaviours to build a cleaner, healthier environment. However, what is less clear is whether this vision can be translated into reality. To help investigate this question, the Network of Social Scientists convened an online workshop in late May. The group of around 30 academics and environmental professionals pooled their expertise to explore the effects of the pandemic on the environment. Through investigating the following three questions they identified a range of impacts and barriers to change, as well as techniques for sustaining positive outcomes as the lock downs ease. What have been the environmental impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic? A diverse range of positive and negative environmental effects were highlighted by NESS experts. Many enforced changes from the lock downs led to environmental benefits: more cycling, gardening and engagement in green spaces, a reduction in food waste and greater support for local businesses and food chains were all suggested. In the workplace, a remarkable transition to an online world challenged the dominance of in-person meetings and international travel, both reducing environmental impacts and increasing accessibility and connectivity. Attitudes may have also changed. Trust in experts was enhanced by the centrality of health experts on daily news reports and other media. Some workshop participants believed more positive attitudes towards our ability to create change had emerged, which could flow onto increased mobilization against climate change. Our ability to collectively shoulder immense economic risks to safeguard our health proved that politics can produce results in times of crisis. Some argued that this has shown that the ‘behaviour change barrier’ can be broken. However, as many social scientists noted, behavioral changes are likely to slide as we slowly return to past habits. As well as this concern, NESS experts highlighted the range of negative environmental impacts which were resulting from the pandemic. The drowning out of attention on bushfires and climate change, the continued practice of ‘ghost flights’, a surge in internet and energy use, and the quadrupling of medical waste indicated a high level of doubt about whether any longer term positive environmental benefits will be sustained. What barriers may prevent our ability to sustain positive environmental effects? The UN Secretary General António Guterres hoped that 2020 would be a pivotal year for addressing climate change. Yet despite the horror of the 2019/20 Australian bushfires, media and political attention swiftly re-focused on the pandemic. As the economic and social costs of the pandemic built, NESS experts noted how political barriers resisting change may once again reassert themselves. The renewed focus on development and jobs might serve as a reason or excuse to cut environmental funding, projects and regulations aiming to protect the environment as has happened in previous economic downturns. The prioritization of a gas led recovery indicates limited political support for a fast transition to clean energy. While calls for an Australian ‘green new deal’ are growing, countering the desire to strip back environmental regulation will require a sustained and powerful collective response. As work and holidays returns to pre-pandemic habits, emissions and other negative environmental impacts resulting from commuting and travel may rapidly rise. Turning changed attitudes and behaviours into habits will likely be difficult. A 50% increase in household waste managed by Australian Councils were foreseen by NESS experts. Pivoting back to eco-friendly behaviours such as public transportation use will be likely be discouraged. The surge in use of public green spaces in wealthier nations could be offset by increased deforestation and biodiversity loss in the Global South as newly unemployed migrant workers return to villages to survive. The economic shock of a recession may reduce public support for implementing environmentally beneficial policies. There are myriad localized and personal barriers which may make sustaining environmental positive behaviours much harder to maintain. What insights from social science can help leverage COVID-19 to achieve positive outcomes for the environment? NESS experts suggested three techniques which could be used to overcome the barriers which will drive a return to ‘business as usual’ as our communities emerge from lock down. First, there is evidence from past pandemics that highlighting the positive personal benefits of changed behaviours can spur lasting change. Past pandemics using this frame drove the development of more green spaces, enabling healthier urban environments alongside increased access to nature. Organisations seeking to advocate for permanent post-pandemic changes could seek to frame their messages referencing the personal benefits of clean air and quieter cities, the benefits to health and personal safety, and the financial and time savings to people and firms from reduced travel costs. Second, NESS experts highlighted the value of capitalising on the momentum we have already built in achieving short term changes. Research on dynamic or change norms highlights that the mere knowledge that a growing number of others have been doing a certain behaviour will increase intentions to adopt that behaviour. Third, NESS experts recommended the use of trusted messengers to communicate about environmental change. Celebrate local businesses cementing in more sustainable post-COVID-19 practices. Capitalize on the increased profile of health experts by amplifying messages from groups such as Doctors for the Environment. Work from within organisations to accelerate change and demonstrate the value of a cleaner and healthier world. COVID-19 has powerfully demonstrated the differences in the power of trusted leaders and voices to mobilise, compared to contested or outsider voices. Already the environmental effects of the pandemic have begun to be documented through a range of academic papers and opinion pieces. Whether for good or ill, the pandemic has shown us that we do have the power to change the impact we have on the world. The challenge is now to build a new reality from this brief moment of hope. The summary report from the workshop is available here. - By Dr. Robyn Gulliver This article was originally posted by NESSAUSTRALIA (Network of Environmental Social Scientists). Problems within our global and interconnected food systems can result in outbreaks of infectious disease spread by bacteria, viruses, or parasites from non-human animals to humans. This is also known as zoonosis. The swine flu pandemic of 2009, for example, was caused by a hybrid human/pig/bird flu virus that originated from dense factory farms where pigs and poultry were raised in extremely cramped conditions together. Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), a bacteria that results in more deaths in the US than HIV/AIDS, also has strong causal link to factory pig farms. SARS-CoV-2, the virus behind the current COVID19 pandemic, may have developed in bats and later pangolins. Both species are regularly hunted for food and medicinal purposes and are sold in wet markets. Wet markets, where live animals comingle in unsanitary conditions provide the perfect environment for diseases to migrate between animals and people. Zoonosis is just one of the many threats posed by the expansion of our food system to global public health. Globally, 72% of poultry, and 55% of pork production come from concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs), or factory farms. For example, chicken CAFOs can hold up over 125,000 chickens. The close quarters and high population inside CAFOs allow the sharing of pathogens between animals with weakened immune systems. Thus, diseases spread rapidly. To safeguard their stock, CAFOs inject low doses of antibiotics into feed. This is intended to lower chances of infection, and conserve the energy animals expend to fight off bacteria in order to promote growth. This method is not without problems; antibiotics are usually administered to whole herds of animals in feed or water, which makes it impossible to ensure that every single animal receives a sufficient dose of the drug. Additionally, farms rarely use diagnostic tests to check whether they are using the right kind of antibiotic. Thus, every time an antibiotic is administered, there is a chance that bacteria develop resistance to it. Resistant bacteria can then pass from animals to humans via the food chain, or be washed into rivers and lakes. Also, bacteria can interact in the farm or in the environment, exchanging genetic information, thus increasing the pool of bacteria that is resistant to once-powerful antibiotics. Due to global trade of meat and animal products, these resistant bacteria can spread rapidly across the globe. A study sampling chicken, beef, turkey, and pork meat from 200 US supermarkets found 20% of samples contained Salmonella, with 84% of those resistant to at least one antibiotic. Another study tested 136 beef, poultry and pork samples from 36 US supermarkets and found that 25% tested positive for resistant bacteria MRSA. Fortunately, in both cases these bacteria can be eliminated with thorough cooking. Nevertheless, more than 2.8 million antibiotic-resistant infections occur in the U.S annually, resulting in more than 35 000 deaths. While antibiotic resistance has been a known issue for some time, policy responses have been mixed. The European Union has prohibited the use of antibiotics to promote growth in animals since 2016. Other parts of the world have been more lax, with nearly 80% of all the antibiotics dispensed in the US fed to livestock, and only 20% on humans. Here at home in Australia, we have one of the most conservative approaches, ranked the 5th lowest for antibiotic use in agriculture among the 29 countries examined. The factory farm system is a modern answer to a modern problem -the rapid rise in global population and demand for meat. While the economies of scale allow factory farms to be more cost-efficient and more competitive in a very crowded market, these come at the expense of every other living thing involved. Further, as our demand for meat is projected to continue rising, so will the issues associated with factory farms: environmental damage from toxic waste pollution, poor animal welfare, the exacerbation of climate change, and poor working conditions. Last year, US Senator Cory Booker unveiled the US Farm System Reform Act of 2019. One proposal from the Bill is to shut down large industrial animal operations like CAFOs. While the Bill is unlikely to pass the Republican-controlled Senate and White House, it signifies the growing public awareness of the wide-ranging problems associated with our food systems. Reducing our meat consumption also comes with personal health benefits, and reduces animal suffering, in addition to reducing the demand for factory farming and the associated health risks. That is not to say a change in dietary habit is without its barriers. Factors such as socio-economic status, access to food, and existing health problems will prevent many from drastically reducing their meat consumption. At the end of the day, our best is all we can do, but as more of us begin taking steps, however small, towards changing our diets, we will make a difference. - By Hannibal Thai *Special thanks to Ruby Green for her assistance in the writing of this post. Every day most of us reap the benefits of collective action undertaken in the past by others. Momentous upheavals play out over centuries as the rights of some and duties of others change in tempo with changing norms and laws. We have seen this play out through history as legal slavery is abolished, disability rights are protected, and demands for Indigenous sovereignty grow. These changes ebb and flow at the macro level, the viewpoint we use to understand changes in society at large. But how do we know what the actual forces of social change are? We must understand the meso-level dynamics of groups, communities and institutions, or investigate even deeper into the micro-level influences on social change fueled by individuals and their activities. Delving into this micro world of activism is how I spent the first year of my PhD. New technologies have enabled digital humanities researchers to gather large empirical databases to investigate the characteristics of social change at the group and individual level. I used these technologies to capture what environmental movement groups and their members are doing, where they are doing it, and what they are achieving. Our findings have been published in two journal articles. Our first paper published in Environmental Communication - The Characteristics, Activities and Goals of Environmental Organizations Engaged in Advocacy Within the Australian Environmental Movement - uses data captured through a content analysis of 497 websites to show how active environmental advocates are. With over 900 campaigns and thousands of online and offline events, they have been busy advocating for environmental care for more than a hundred years. Furthermore, most of their efforts are not radical, with activists predominantly working as volunteers in our local communities with the aim to increase awareness and understanding about more pro-environmental behaviors. But activity is one thing; outcomes are another. We wanted to know whether this activity is successfully effecting change. To investigate, we went back to the micro level to ascertain the outcomes of climate change campaigns. The causes of climate change are intractable, diffuse, and woven into the fabric of our social, political and economic systems. So how do activist groups try to stop climate change, and is any one way more successful than the others? Our findings were published in the paper ‘Understanding the outcomes of climate change campaigns in the Australian environmental movement’ in the journal Case Studies in the Environment. We identified the target and goal of 58 campaigns specifically focusing on climate change and tracked their outcomes over a 2-year period. Some of these campaigns aimed to stop new coal mines. Some of them wanted government to enact new climate policies. Our data showed that almost half of these campaigns either fully or partially achieved their goal. For example, coal mines were delayed, and climate policy was enacted. In particular, 63% of campaigns asking individuals, businesses and health and education providers to reduce their climate impact were either partially or fully successful. In total 49% of all campaigns achieved full or partial success. These campaigns each only focus on one small piece of the solution to climate change and we cannot be sure how much campaign activities directly influence outcomes. Yet our research using real-world data shows that these environmental groups are connected to, and likely playing a crucial role in driving meaningful change which will help protect the environment. These activities constitute the incremental successes and failures which together drive social change. - By Robyn Gulliver When reflecting on what social change and social movements look like, images of activists protesting and engaging in other acts of civil resistance likely spring to mind for most people. However, this isn’t the only way to be a change agent. There are a myriad of ways that people can aide social change without engaging in ‘traditional’ forms of activism. In fact, we can only maximise the impact and potency of social movements if we diversify our tactics and have people ‘fighting the good fight’ in different ways. Below, I outline five common change agent roles and their effectiveness in different domains of the social change process to highlight the varied and equally valuable ways we can all contribute. The Activist The term activist can generally be understood as a person participating in collective action to further a cause or issue. Here, I focus on people who operate outside of formal systems or institutions to call public attention to injustice and agitate for social change using conventional and, in some cases, more radical tactics (e.g. Extinction Rebellion protesters blocking off bridges and main roads). When conducted appropriately, these actions can increase public support and discussion of the social issue. However, these approaches can also reinforce stereotypes that activists are ‘extreme’ which, in turn, may deter collective action participation among observers. The Insider Although activists can advocate for change outside the system, oftentimes social change messages are better received from ‘insiders’ or people who belong to the same groups or institutions that activists are trying to influence. As criticisms are trusted more when coming from ingroup members, insiders can make social change messages more palatable to the target group and may, in some cases, be able to communicate activists’ messages and concerns in terms that the ingroup can understand and be swayed by. The Scholar The Scholar’s role is twofold: to conduct rigorous and ethical research about social issues (e.g. the prevalence and impact of discrimination, the existence of anthropogenic climate change); and share this knowledge to inform public understanding of and discussions about these issues. Scholars can be academics at universities, members of research organisations (e.g. OurWatch), or, in some cases, organisations that share data about the prevalence and impact of social problems (e.g. Children by Choice publishing reports about the prevalence of Domestic Violence among their clients seeking terminations). Scholars’ ability to uniquely access and share this information can help to inform the general public’s understanding of social problems, fight misinformation, convince relevant stakeholders about the importance of an issue, and proffer evidence-based solutions. Indeed, social justice research can be used to successfully challenge and dismantle institutional prejudice and foster transformative social change by informing public policy and interventions. The Teacher An oft-overlooked role in social change is that of the teacher: a person who can foster civic engagement through formal education (e.g. primary, secondary, and/or tertiary education) or informal education (e.g. service-learning opportunities). Formal, classroom based educational interventions promote engagement with political issues and voting, while service-learning increases interest and participation in community-based action. Further, educational interventions can also be used to reduce prejudice toward disadvantaged groups. Thus, taking an active role in shaping people’s understanding of politics and social issues can positively influence their attitudes and political participation. The Constituent Constituents, or the general public, are often the numerical majority in social movements. They can include people who are sympathetic to but not committed to participating in actions for social change, or people who disagree with and resist social change messages. Unsurprisingly, constituents can greatly sway the progress of social movements, in that the attitudes and values they choose to adopt or reject influence the outcomes of state and federal elections, the types of laws and policies that governments and industries support, and broader norms in society. Thus, constituents have the power to elect leaders who support social change, call out unfair treatment and subvert anti-egalitarian norms, and support organisations and brands that make ethical choices (e.g. cruelty free cosmetics). Perhaps most importantly, other changes agents must make a considered effort to ensure that constituents have the information and support they need to make informed decisions and use their civic, relational, and economic powers effectively. Moving Forward Although the number and nature of these roles will likely vary between movements and socio-political contexts, they represent the diverse yet equally important forms of change agent work that can enhance the impact and effectiveness of social movements. The question now is: what role(s) do you play? How can you harness your unique skills and forms of influence to aid social change? Regardless of your answer, remember that just because you haven’t attended a protest or blocked oncoming traffic doesn’t mean that you aren’t a change agent. - By Morgana Lizzio-Wilson Disruptive protests gain media attention. For many people, this media attention might be the first time they learn of a particular social or environmental movement. his tactic and resulting media coverage often prompt predictable responses from the public and officials. Why, some ask, are protestors blocking roads instead of standing on the pavement educating people? Why protest if they don’t have a solution? But herein lurks a pervasive misconception of what activism actually is. Acts of civil disobedience enable awareness of a movement to bubble to the surface of daily life because they are newsworthy. However, this media attention can mask the years of relentless campaigning which builds the scaffolding to sustain these moments of shock. This scaffold is the groundwork done by the foot soldiers of a movement. Work done day after day, year after year, labouring at the often unseen toil that is the bread and butter of activism: recruiting volunteers, educating people and creating solutions. These tactics aren’t newsworthy. And sometimes to activists, they may feel like failure, creating the justification for the emergence of radical action. Does that mean that this toil was futile? Or, as argued by Extinction Rebellion, that tactics are now only just beginning? Coordinated acts of civil disobedience do not emerge spontaneously from an empty well. Take the American civil rights movement. Yes, Rosa Park’s determination to hold her bus seat created an iconic moment which helped galvanise the movement towards its goals. However, Rosa Parks was a long-term activist who, for decades, fought relentlessly against school segregation, wrongful convictions of black men, and anti-voter registration practices. Many other people had, in fact, held bus seats before her. She was one of thousands, many of whom, like her, were on the verge of exhaustion after perceiving that their years of activism had produced little change. We could look at any moment of newsworthy radical action and find parallels. Take the Salt March, an iconic moment of disobedience is now inextricably linked to the success of the Indian Independence movement. Organised as a defiant act against British rule in India, it was however, just one of the many tactics used in the 90 long years of struggle. Here in Australia, recent acts of civil disobedience for climate change action have emerged from a rich and vibrant foundation of environmentalism. Thousands of groups have been running thousands of campaigns across an array of issues. Activists have engaged in radical action against mining, logging and other destructive environmental practices for many years, using a diverse range of tactics for their cause. What were these tactics? Building groups, training volunteers, handing out flyers, organising workshops, visiting politicians, contacting polluting companies, developing policy frameworks. These tactics can successfully generate change. Almost half of the campaigns focussed on climate change achieved their goals, without the use of civil disobedience.

As social change researchers we look to understand the potential of tactics to generate change. But when we research activism, it is important to look beyond the headlines. Civil disobedience is not where ‘tactics begin’. As a movement works to raise awareness, create sympathy, motivate intentions to act, and ensure implementation, civil disobedience may instead be the end of the beginning. - By Robin Gulliver “Tell the truth and act as if the truth is real” – so goes the slogan of Extinction Rebellion (XR), a new international movement started in London in October 2018. The statement points to a discrepancy between the dire state of our environment and the lack of a real sense of emergency. While the majority of Australians’ understanding of the urgent need for action against climate change is reflected in their various every-day behaviours, there is still a lack of engagement in collective action for the environment. Despite the rise in individuals’ environmentally friendly behaviours, emissions continue to rise year after year. With 82% of all government subsidy still concentrated in ‘Clean Coal’, it’s clear that public policy still doesn't go far enough. While it might be more appealing to focus on improving our every-day behaviour as individuals, some argue that the pervasive messaging to get us to live our ‘best green life’ is actually a distraction designed to keep us content and away from collective action. However, there is a recent collective awakening about the need for systemic change over just changes in individual behaviour. These desperate times see the rise of more desperate measures of collective action such as non-violent civil resistance. Its practices and successes can be traced back to the Suffragettes, the American Civil Rights Movement, and LGBTQ movements. The specifics and strategies of civil resistance movements vary depending on their purpose and contextual factors. In this post, we’ll focus on civil resistance in the context of climate change action. The key principles remain similar across the movements:

Relevant audiences. Disruption is more effective in capital cities, as these are typically where national and international media are based. Just as labor strikes are effective against companies, closing down capital cities may be effective against governments. The inconvenience and disruption to the local populace and businesses is unavoidable. This can be harmful to the movement, so it’s important to inform the public about the urgency of the situation and the rationale behind the disruption. Prolonged disruption should be prewarned so emergency services can be rerouted.

Given the disruptive nature of civil resistance, public opinions can be quite divided. But if the sizes of the recent School Climate Strikes are anything to go by, the public’s appetite for drastic changes is growing rapidly, and this may come with corresponding greater support, or at least acceptance, of civil disobedience for climate change action. Environmental movements have to work to ensure that the political capital from mass mobilization for action isn’t wasted, as policy makers attempt to turn the conversation away from addressing climate change towards the law-breaking. Allies, policy makers, and the public have to be continually reminded that the story is about the science, the urgency of change, and the mass support for that change. Meanwhile, it’s up to the civil disobedience movements to galvanize support by informing the public about the movement’s rationale and considerations, and being inclusive of allies with varying political persuasions and beliefs. Regardless of whether you support civil disobedience or prefer more moderate activism, if there is a time to want more from our political system, the time is now. - Hannibal Thai When groups of people actively help each other (“intergroup prosociality”), what is the driving force? Are all types of helping motivated by the same psychological processes? In a recent paper, we delved into these questions by reviewing what we know of intergroup prosociality from a psychological perspective Benevolent support or political activism? When we think of all the ways that people show concern for others, we may start listing things like donating to international aid campaigns, listening to stories of suffering with empathy, or marching in a rally to bring about more equitable conditions for a disadvantaged group. Do all of these stem from the same values or beliefs? In this paper, we argue that there are two different ways people engage in inter-group prosociality - benevolence and activism. Benevolence aims to compassionately alleviate the suffering of others. Acts such as charitable giving, or listening empathetically to the painful experiences of others would fall under this category. Activism aims to create change in social and political systems to bring about greater equality. The focus here is the recognition of harm and disadvantage brought on by systems, and working to challenge these systems through group-level action. Many types of collective action fall into this category. This distinction forms the basis through which we view how groups of people engage in various forms of prosociality. But of course, there are complexities! For example, how should charitable giving be categorised? – Is it benevolence, activism, or both? While charitable giving has been mostly studied in a way that lends itself to the benevolence definition we provided, charitable giving can also be motivated by motives to bring about equality, and giving to charities that are most likely to bring about structural social change. This argument complicates our traditional view of charitable giving and presents evidence that charitable giving can be both! And what about intergroup contact – What does it have to do with intergroup prosociality? Intergroup contact refers to exchanges between individuals of two different groups, and when it is positive, it has been shown to reduce the prejudice of advantaged group members towards stigmatized groups. Positive contact could be argued to be associated with benevolence rather than activism. Yet recent research on contact has shown that positive contact between advantaged and disadvantaged groups, while reducing the prejudice of advantaged group members, also weakens the disadvantaged groups’ motivations to engage in activism on their own behalf. In this way, contact can reinforce the inequality between advantaged and disadvantaged groups. So what is the solution? Is the choice between mobilizing the disadvantaged group or reducing the prejudice of advantaged groups? Not necessarily. Recent work shows that when the advantaged group acknowledges the inequality and explicitly supports social change, it promotes both groups’ activism as well as positive attitudes. This type of contact has been termed supportive contact. Finally, is there a distinction between allyship and solidarity? Although the terms are often used interchangeably, we make the argument that it might be useful to think about how the motives for the two are different. In Allyship, the advantaged group is helping the disadvantaged group because of some benefit to themselves, for example for their own political aims, to conform to their own group’s norms, or to act out their values. However, when one group stands in solidarity with another, it can mean that they feel identified with that group. In other words, allies might feel part of a larger group together with the people they are helping (“we are all Australian”, or “we all want gender equality”). If there are two different types of motives, we can look at which ones are more common, last longer, or are more likely to spur real change. For example, maybe allyship motives are more common, but solidarity motives are stronger and more likely to lead to social transformation! The paper also highlights an exciting and emerging trend in solidarity research to move beyond advantaged and disadvantaged group dynamics, and look at how disadvantaged groups engage in solidarity with each other. onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/spc3.12436

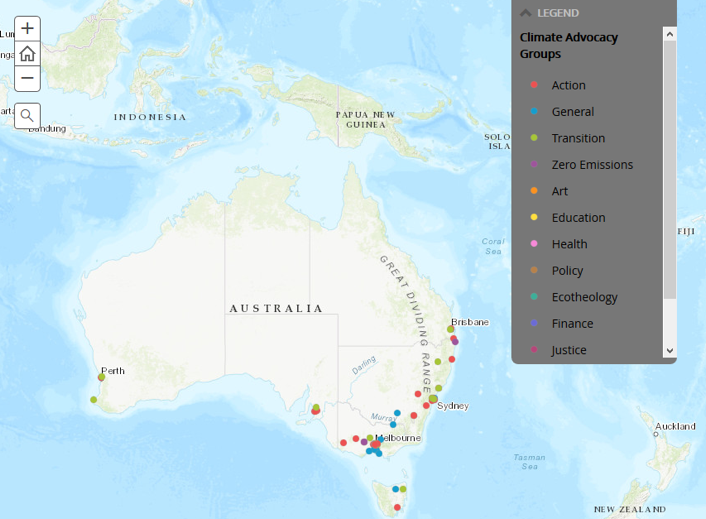

For those interested in intergroup relations, this paper details the many ways groups engage in prosociality with one and other. It provides a detailed review of the research and a helpful way to understand and distinguish between benevolence and activism when we consider the ways groups engage in helping with each other. We look forward to any feedback! - Zahra Mirnajafi This blog post is based on: Louis, W. R., Thomas, E., Chapman, C. M., Achia, T., Wibisoni, S., Mirnajafi, Z., & Droogendyk, L. (2019). "Emerging research on intergroup prosociality: Group members' charitable giving, positive contact, allyship, and solidarity with others." Social and Personality Psychology Compass 13(3): e12436. Activists are time and resource poor. They create social change by making quick decisions in stressful conditions, and often suffer disproportionately for their efforts. Given the urgency of our social and environmental challenges, linking activists with the latest research on topics ranging from how to engage in effective communication, to tactical decision making, to activist self-care, is more important than ever. Yet this research is mostly hidden behind paywalls or it is time consuming to acquire and apply. Thankfully, digital technologies offer a new opportunity to bridge the activist-researcher. Throughout my time here in the Social Change Lab, I’ve experimented with piloting effective research dissemination. This has lead me to the development of my website, www.earthactivists.com.au. This website began as a communication vehicle for various projects created during my time as a fellow in the University of Queensland Digital Research Fellowship program. The website is based on an initial dataset of 497 Australian environmental groups and 901 environmental campaigns. Mapped through the Esri ArcGIS online platform, the data and associated map will allow activists to easily view campaigns across all environmental issues, compare the data available on them, and track the campaign outcomes over time. Combined with archives collected on past environmental campaigns, one goal of the project is to create an open and accessible ‘treasure chest’ of information on Australia’s rich and diverse environmental movement. Open data can inform what type of activism is more likely to succeed; for example, data collected on over 100 years of protests demonstrates the surprising success rate of non-violent civil resistance as opposed to violence insurgencies. But it can also help enable stronger and more connected activists, reducing the ‘activist fatigue’ experienced through isolation and burnout. To this end, the website hosts stories of women fighting climate change. It also provides insights from experienced environmental campaigners on the highs and lows of activism, how they define success, and how they prioritise and acquire resources for their work. This website, still in its nascent stage, has been informed by international examples of accessible and open data on social change movements. One of the most influential of these examples is the Nonviolent and Violent Campaigns and Outcomes Data Project (NAVCO). This publically available dataset, initiated by Erica Chenoweth, has generated findings of international significance about the importance of non-violence civil resistance, and initiated a new research direction in civil resistance. Another successful open data initiative is that of the Environmental Justice Atlas (ejatlas.com). Centred on a global map of large scale environmental civil resistance campaigns, the project aims to both serve as a tool for informing activism and advocacy, and to foster increased academic research on the topic. Containing information on 2,100 environmental justice case studies, this project has international collaborators both contributing to new case studies and utilising existing studies for their activism and research. These examples demonstrate the new ways digital technology can be used as a bridge between activists and researchers. We have such a rich history of activists and activism around the globe. Collecting and sharing detailed empirical data about social and environmental collective action can help celebrate the work of those who fought for social and environmental justice in the past. But equally importantly, it can help inform how we can generate the urgent action we need to secure our future. In this time of crisis, bringing activists and researchers together is one more important than ever.

- Robyn Gulliver This blog post is the third summarising a special issue of PAC:JPP on the role of social movements in bringing about (or failing to bring about!) political and social transformation. I co-edited the special issue with Cristina Montiel, and it is available online to those with access (or by contacting the papers’ authors or via ResearchGate). Our intro summarising all articles is also online ‘open access’ here, along with the first two blog posts, dealing with tipping points or breakthroughs in conflict and the non-linear nature of social transformation and the wildly varying timescales. Some of these themes are also dealt with in a 2018 chapter by our group *. The overall aim of the special issue was to explore how social movements engage in, respond to, or challenge violence, both in terms of direct or physical violence and structural violence, injustice, and inequality. As well as the six papers summarised previously, there were four fascinating additional pieces by Montiel, Christie, Bretherton, and van Zomeren. Together the authors take up important questions about who acts, what changes, and how social transformation is achieved and researched, which I review below. Who can participate in the scholarship of transformation? Montiel’s (2018) piece “Peace Psychologists and Social Transformation: A Global South Perspective,” identifies barriers to full participation in the scholarship of peace. These barriers often include a relative lack of resources, and exposure to military, police, and non-state violence and trauma. In publishing, scholars and universities in the Global South face a difficult political environment in which both their silence and their speech may affect their careers and even their lives. More routinely, selection bias by journals to privilege the theoretical and methodological choices and agendas of the Global North marginalises the research questions that are most pressing, or most unfamiliar to WEIRD readers (Western, educated, industrialised, rich, democratic; Heinrich et al., 2010). In the short term, Montiel calls for professional bodies to open schemes for developing academics from the Global South; and for peace psychologists to co-design projects and conduct analyses and writing with southern scholars to allow a wider range of voices and ownership of the project. What is it that changes in social transformation? Van Zomeren’s (2018) piece “In search of a bigger picture: A cultural-relational perspective on social transformation and violence”, takes up his selvations theory as a springboard for understanding social transformation. He conceives the self as akin to a subjective vibration within a web of relationships (a selvation), which would both influence and be influenced by changing societies. Drawing on his earlier work on culture and collective action (e.g., van Zomeren & Louis, 2017), he suggests that the central challenge of the social psychology of social transformation is keeping the micro, meso, and macro-level variables in the same frame, and allowing emergent relationships within theoretical models. In the van Zomeren model, the decision-making self is embedded within relationships, with the regulation of those relationships a central goal of the actor. Thus relational norms for violence (or peace) become proximal predictors of change – which in turn rest on wider social norms and expectations of opponents’ actions (see also Blackwood & Louis, 2017). Violence may affirm or contradict the relationship models of the actors creating social change, which manifests as changing relationships with others: movement co-actors, targets, and the broader community. Christie and Bretherton, below, also echo the contention that it would be useful for scholars and practitioners to consider more deeply how social change involves changing relationships and the self. Five Components of Social Transformation Christie (2018) presents an analysis of effective social transformation movements, arguing that there are five components that campaigners and scholars must engage. A systemic approach is the foundation of social transformation, he proposes: transformation entails the creative construction and destruction of existing relationships and the development of more or less just and violent new ones. Sustainability is a second component: both the outcomes of a movement and its processes will last longer over time or less so. Momentary failures (and successes) are common; it is also the case that in the face of countervailing forces and counter-mobilisation, to sustain a positive status quo may require constant renewal and refreshment of social movement support. Third, a movement must also have the capacity to scale up, which often requires new skills, leadership, and institutional support – or more broadly, the ideological and organisational foundation to build new alliances and engage new topics and opportunities without compromising its values and direction. The fourth component of socially transformative movements is the inclusive involvement of those who are more powerless and marginalised: without active outreach and proactive inclusion, many movements re-invent old hierarchies and affirm old power structures. Finally, Christie closes with an interesting reflection on the metrics of social transformation, and the different conclusions that one might draw in mobilising to achieve greater lifespan, wealth, well-being, and/or cultural peace. Social Transformation: A How-To For Activists