|

Incidents of racial discrimination are all too common, but only recently have such incidents been highly publicized and shared widely on social media. Here are some examples:

Being largely unaware of the pervasive discrimination faced by Black people and other minoritized groups in the U.S., White people have had often felt little need to do anything about it. Indeed, only a small proportion of White Americans have protested for racial justice, and those who do take action typically report close ties with people from racial and ethnic minority groups. But as millions witnessed the brutal killing of George Floyd while in police custody, we have seen more White people taking to the streets than ever before to protest for racial justice. Thanks in part to social media, White people are beginning to recognize everyday racial profiling and the severity of racial discrimination, and as a result, they are becoming more aware of the White privilege they enjoy. We surveyed nearly 600 White Americans to ask how often they have witnessed an incident of racial discrimination targeting Black people in their day-to-day lives—for example, a Black person being treated differently than other people would be treated at restaurants or stores. We also asked about their awareness of racial privilege and their willingness to take action for racial justice and equality, such as protesting on the streets and attending meetings related to Black Lives Matter protests. Whites’ reported willingness to take action for racial justice was quite low. But the more frequently White people witnessed racial discrimination, the more willing they said they were to take action against racial injustice—and this effect was largely due to their greater awareness of racial privilege. In our next study, we focused on White people who described themselves as “allies” in the pursuit of racial justice, and who had previously taken at least some action to promote racial justice. Once again, we found the more frequently White people witnessed racial discrimination targeting Black people, the more they became aware of racial privilege, and this, in turn, predicted their greater willingness to take action against racial injustice. We next tested experimentally whether exposure to incidents of racial discrimination would lead White Americans to become more aware of racial privilege and more willing to protest for racial justice. Half the participants viewed videos depicting well-publicized incidents of racial discrimination such as described earlier, while the other half viewed only neutral images. Results showed that White participants who viewed the discriminatory incidents reported greater awareness of racial privilege and tended to become more motivated to take action for racial justice. It thus seems that greater awareness of racial privilege can grow from witnessing incidents of racial discrimination indirectly, such as through videos on social media and news reports, without being personally present at such events. These results offer hope that further steps toward racial justice may be taken as White people become more aware of both racial discrimination and their own racial privilege—and, in turn, become more motivated to take action against racial injustice. - By Özden Melis Uluğ & Linda R. Tropp Özden Melis Uluğ is a lecturer in the School of Psychology at the University of Sussex. Linda R. Tropp is a professor of social psychology at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. This post is previously published on the Society of Personality and Social Psychology; Character and Context Blog For Further Reading Case, K. A. (2012). Discovering the privilege of whiteness: White women’s reflections on anti-racist identity and ally behavior. Journal of Social Issues, 68(1), 78–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2011.01737.x Tropp, L. R., & Uluğ, Ö. M. (2019). Are White women showing up for racial justice? Intergroup contact, closeness to people targeted by prejudice, and collective action. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 43(3), 335-347. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684319840269 Uluğ, Ö. M., & Tropp, L. R. (2020). Witnessing racial discrimination shapes collective action for racial justice: Enhancing awareness of privilege among advantaged groups. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12731

0 Comments

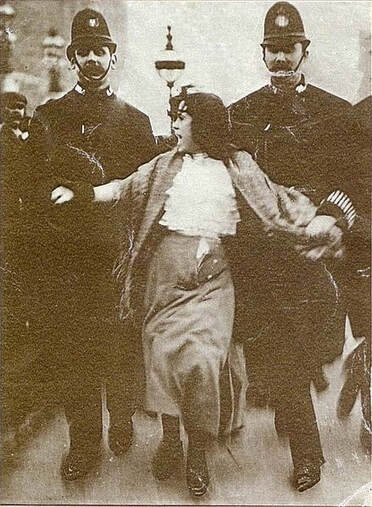

Who Runs The World? …Girls?: Why Female Leaders Struggle to Mobilise Individuals Toward Equality1/7/2019 Have you ever noticed that women are typically the ones spearheading gender equality movements? Think of the suffragettes, the #MeToo, and #TimesUp movements, the March for Women; All fronted by women – but at what cost? Research increasingly shows that relying solely on female leaders is not enough to achieve equality. Perhaps in response to this, there’s been a recent upsurge in male-led initiatives, such as the HeForShe movement, and the Male Champions of Change initiative. Both of these call on men to use their privilege and power to place gender equality on the agenda. These types of initiatives aren’t just companies taking a stab at something new – they’re backed by social psychological research. For example, two recent studies looking at how leader gender affected individuals’ responses to calls for equality found that men and women were more likely to follow a male leader into action (Hardacre & Subasic, 2018; Subasic et al., 2018). Importantly, the only change between the study conditions was the leader’s name and pronouns (e.g., from “Margaret” to “Matthew”). Below, we talk about some of the reasons why female leaders struggle to mobilise people toward equality. “Think manager, think male”: Leadership prototype embodies masculine attributes In our heads, we hold a 'prototype' of particular categories and roles – a fuzzy set of characteristics, attitudes, and behaviours that define certain groups and occupations. For example, if you were to think of a leader, you might think confident, assertive, and even male. Turns out this “think manager, think male” mindset is pervasive. Numerous leadership theories emphasise the desirability of stereotypically masculine traits in leaders. In fact, female leaders are frequently seen as ineffective because individuals’ ideas of effective leadership overlap with agentic male stereotypes (assertive, dominant), rather than communal female stereotypes (warm, nurturing). Even when female leaders do adopt masculine behaviours (such as those seen as typical of leaders), they face backlash because they’re seen as “violating” their traditional caring stereotype. This signifies a Catch-22 situation whereby female leaders are “damned if they do and doomed if they don’t!” Female leaders face accusations of self-interest, while male leaders are seen as having something to lose. It’s also difficult for female leaders of gender equality movements not to appear self-interested and overly invested in their cause (with good reason, given that it IS in their group’s best interests to challenge the status quo!). Essentially, women’s efforts at reducing inequality can be seen as furthering the interests of themselves and their group, and the more women are viewed as trying to benefit their own group, the more cynicism and dismissal they encounter. This can undermine women’s efforts at social change because acts of self-interest are less convincing and influential than acts that seem to oppose one’s best interests. In contrast, because many view gender equality as a zero-sum game, when men challenge gender inequality they’re seen as having something to lose – namely the rights and privilege that accompany their membership of a high-status group. This ultimately affords men greater legitimacy and influence, and therefore greater ability to mobilise followers. Male leaders possess a shared identity with men and women, while female leaders only share an identity with women. Possessing a shared identity with those you are trying to mobilise is at the crux of effective leadership, because those considered “us” are considered more influential than “them”. Herein lies another problem for female leaders. In gender equality contexts, male and female leaders both share a cause with women engaged in gender equality movements whilst men benefit from an additional shared social identity with men.. Meanwhile, no such shared identity yet exists for female leaders looking to mobilise a male audience. Instead, they’re seen as outgroup members by men in terms of their gender group membership, but also in terms of shared cause because gender equality is often seen as a women’s issue and of no benefit to men. Conclusion Paradoxically, by virtue of their gender and the privileges it permits, male leaders seem to have the ability to undertake gender equality leadership roles and mobilise men and women more effectively than female leaders. Research suggests that, among other reasons, this is due to leadership prototypes typically comprising masculine attributes, female leaders’ inability to escape accusations of self-interest, and male leaders’ possession of a shared identity with both male and female followers. It will be interesting to see how long the male ally advantage persists: in the longer term, effective feminist leadership will presumably eliminate the ironic inequality. - Guest post by Stephanie Hardacre (University of Newcastle). In the past week, we have seen horrifying pictures from the U.S.-Mexico border where U.S. Border patrol has fired tear gas on asylum seekers from Central America. This is part of a new stance on immigration by the American White House, which includes deploying 5,000 US troops to the southern border, and giving the green light to use lethal force. While many are outraged at the use of such force by the government, others have been quick to defend the “America First” strategy. More broadly, anti-immigration sentiments have been expressed more frequently in a range of countries around the world, from France introducing stricter guidelines for asylum to Australia, where a sharp rise in anti-immigrant sentiment has been reported.

How can we explain antagonistic views towards immigrants and asylum seekers? While understanding perspectives on both sides is complex, recent research sheds light on the challenges associated with the reception of immigrants and refugees in Western countries. “America First” ... the role of national identities What we believe about who we are has a strong role in shaping our views of the world. In the U.S., proponents of using excessive force on asylum seekers justify this approach as putting America’s national interests first. What we know from the science is that those who believe being an American is an extremely important part of who they are, in other words, those who have a strong American identity, also are likely to have more negative attitudes towards immigrants. Is connecting pro-America feelings with hostility to foreigners inevitable though? No. First, it turns out that the link between stronger American identity and welcoming foreigners can also be positive for some! Americans who define the nation inclusively are more welcoming to newcomers, whereas those who have a narrower view of the country are more hostile. When we are tough on immigration, are we tough on all immigrants in the same way? Being tough on immigration is not applied the same way to White immigrants as it is to people of color. In one study, White Americans reported that the use of harsh punishment for a suspected undocumented immigrant was more fair when the suspect was Mexican, than when the suspect was Canadian. Earlier we spoke about the content of identities, and that discussion is also relevant here. The more people understand being American as being Anglo, the more lenient they are with those who look Anglo. Around the world, the broader and more inclusive our understanding of what it means to be a citizen of a country, the more diverse people we would be willing to welcome as new immigrants and refugees. The language we use has serious consequences Finally, it is striking how the language used to describe asylum seekers and immigrants by politicians or news media can conjure up images of hordes of animals, scurrying towards us. This type of language is dehumanizing, and research shows it has serious consequences. Endorsing harsher immigration policies is one outcome of dehumanizing language and using dehumanizing language can increase anger and disgust towards immigrants. The use of vermin metaphors to describe Jews during the Holocaust comes to mind when we think of how dehumanizing language has been used to justify atrocities. Indeed, the use of such language is one of the precursors of genocide. Therefore, while news reports describing immigrants in animalistic language may go unnoticed, the reality is that this language has the potential to lead to dire consequences for the world we live in. The topic of immigration is complicated and the challenges and opportunities of migration are important for both immigrants and the host societies that receive them. An evidence-based approach to understanding the issues and the sentiments on both sides are needed for our societies to move forward to a more socially cohesive and peaceful world. - Zahra Mirnajafi As societies have developed, technological advances and medical discoveries have increased life expectancy and made our lives seemingly easier. But this development is not experienced equally by all people. In general, industrialised nations have a high quality of life. Yet stark differences remain in how wealth and benefits are spread across society. This is called income inequality. Sadly, income inequality is a global phenomenon. The distribution of wealth across the globe shows that 71% of the world’s population hold just 3% of the global wealth. On the other hand, 8% of the population hold over 84% of the world’s wealth. Income inequality is especially pronounced in the United States, where the income gap is twice that of the rest of the industrial world. So you might be thinking, why is this important? Here are 3 reasons why you should care about income inequality: 1. Less happiness and life satisfaction The more wealth a society has the happier that society will be, right? Well, not quite. In 1974, Economist Richard Easterlin showed that Americans were not happier during periods of high economic growth. Some countries, however, do show increased happiness with increased economic growth. What can explain this difference? Income inequality. In a study of 34 countries, researchers found that when income inequality is high, increased economic growth is not associated with increased happiness. When economic inequality is high and people can see the wealth of others, it may make their relative lack of economic prosperity more obvious. We become aware of the differences in our own economic gains, and the difference in our lifestyles. This, in turn, can reduce our sense of happiness and wellbeing. Reflecting on how we consume social media, platforms such as Instagram give us daily access to the life of the rich, through accounts like the rich kids of instagram, which boasts “They have more money than you and this is what they do.” 2. More obesity and related health problems When thinking about how income inequality affects health, it’s reasonable to think that your personal wealth would be the main determinant of your personal health. You may conclude that income inequality only affects the health of the poor, but you’d be wrong. Higher obesity and related health conditions such as diabetes, cancer, and heart disease are present amongst all social classes in societies with higher income inequality. Regardless of personal wealth, people living in countries with greater income inequality experience poorer health outcomes than their counterparts in more equal societies. People in a laboratory setting, who were made to feel relatively poor, ate 54% more calories, rated the high calorie food as more enjoyable, and were more likely to want to buy higher calorie food in the future that those who were made to feel rich. Outside of the laboratory we also find that the more income inequality, the higher rates of obesity in a society. This shows us that inequality has a direct effect on our lifestyles. 3. Less generosity and trust Higher income inequality makes the wealthy less generous and breeds a sense of entitlement—the belief that one is more important and deserving than others. However, in more equal societies, the wealthy are just as generous as the poor. People in areas with high income inequality also trust each other less. When there is less trust in society, people are more likely to only look out for themselves, and their families. Communicating inequality

We’ve established that inequality has detrimental effects for all. Yet it is not always communicated as something that is bad. Politicians often frame inequality in a way that hides the full picture. They highlight economic mobility—the sense that everyone can move up the wealth ladder—and related concepts such as the American Dream. For example, Rick Santorum recently said: "There is income inequality in America, there always has been, and hopefully, and I do say that, there always will be. Why? Because people rise to different levels of success based on what they contribute to society.” Be aware that this framing has profound effects on our psychology. People become more tolerant of income inequality the more they perceive economic mobility. In truth, economic mobility is not as widespread as people think. So next time you hear politicians praise inequality, remember the burden falls not just on the poor, but on all of society. - Zahra Mirnajafi Why do people do things that harm others? Socially harmful behaviours, like discrimination and hate speech, are still common in modern society. But where do these behaviours come from? According to self-determination theory, pro-social behaviours (like tolerance and fairness) come from within, because we have a personal desire to engage in them. In contrast, harmful acts are normally motivated by an external source, such as social pressure to conform. For example, school bullying may be encouraged by those classmates that intimidate other students. In order to avoid being bullied, and also to become close to the popular children in school, some kids may also start bullying others. To summarise, helping other people gives us real pleasure and enjoyment, while harming others only brings recognition from others and helps achieve our goals.

Even though discrimination is not truly motivated by our own values and beliefs, from this perspective, is it possible that harmful behaviour can become a part of our identity and represent who we really are? Discrimination can be a consequence of social norms One cause of discrimination are the social norms associated with the groups we belong to. In an attempt to fit into society, we follow the norms of our own groups. These norms, however, are not always oriented to benefitting the interests of people in other groups. For example, an organisation with racist norms that dictate choosing job candidates that belong to the Caucasian ethnic group rather than choosing based on qualifications, will motivate the recruiter to follow these norms and to discriminate against certain ethnic groups. We may follow discriminatory norms in order to feel we fit in with our group, or that doing so promotes our group’s values or goals. When a behaviour is considered normal in groups we belong to, but is actually inconsistent with what we personally believe in, this creates a sense of conflict within our identity. Compartmentalisation helps us deal with inner conflict This feeling of contradiction between our values and our situation reflects an underlying resistance to engage in harmful actions. For example, a recruiter who personally believes that job candidates should be hired based on their merit will feel an internal conflict when following the firm’s discriminatory norm. In response to inner conflict, we tend to separate the harmful (e.g., discriminatory) behaviour from other life situations and contexts. This is called compartmentalisation. Going back to the example where Caucasian candidates are preferred when hiring, this would mean that the conflicted recruiter would restrict ethnic discrimination behaviour only to work situations and would not generalise it to other life contexts. By using this compartmentalisation strategy, the harmful social behaviour is restricted to a particular life context and does not become representative of the entire person. From the self-determination perspective, compartmentalisation also protects one’s identity from negative evaluation. People do not enjoy discriminating against others Many people want to believe that human nature is inherently good, and that no one would willingly harm others and feel good about themselves. The results of our studies confirm that people who discriminate do not necessarily enjoy their actions harming others. Rather, they are more likely to feel an internal conflict when discriminating. On this positive note, we conclude that harmful behaviors are somewhat more difficult to accept as a part of who we are. Although specific life situations may sometimes dictate discriminatory actions, they generally bring less pleasure and enjoyment. Instead, causing harm to others evokes feelings of internal conflict and dissociation, which the majority of us will try to minimise. - Guest post by Ksenia Sukhanova and Catherine Amiot, Université du Québec à Montréal *** Read full article: Amiot, C. E., Louis, W. R., Bourdeau, S., & Maalouf, O. (2017). Can harmful intergroup behaviors truly represent the self?: The impact of harmful and prosocial normative behaviors on intra-individual conflict and compartmentalization. Self and Identity, 1-29. |

AuthorsAll researchers in the Social Change Lab contribute to the "Do Good" blog. Click the author's name at the bottom of any post to learn more about their research or get in touch. Categories

All

Archive

July 2024

|

Social Change Lab

Join our mailing list!Click the button below to join our mailing list:

Social Change Lab supports crowdfunding of the research and support for the team! To donate to the lab, please click the button below! (Tax deductible receipts are provided via UQ’s secure donation website.) If you’d like to fund a specific project or student internship, you can also reach out directly!

|

LocationSocial Change Lab

School of Psychology McElwain Building The University of Queensland St Lucia, QLD 4072 Australia |

Check out our Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2017

RSS Feed

RSS Feed