|

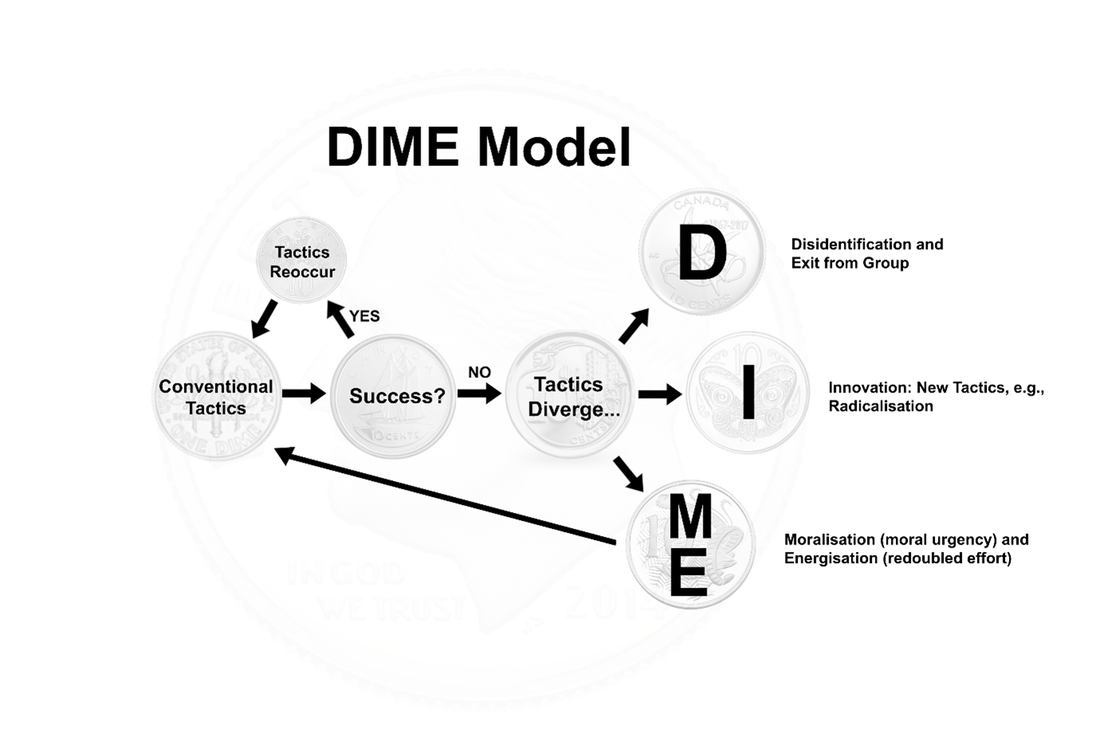

Collective action is a key process through which people try to achieve social change (e.g., School Strike 4 Climate, Black Lives Matter) or to defend the status quo. Members of social movements use a range of conventional tactics (like petitions and rallies) and radical tactics (like blockades and violence) in pursuit of their goals. In this blog post, we’re writing to introduce DIME, which seeks to model activists’ divergence in tactics. The theoretical model is published in an article on “The volatility of collective action: Theoretical analysis and empirical data”, published online here in Advances in Political Psychology. The model is named after a dime, which is a small ten cent coin in some Western currencies. In English the expressions to “stop on a dime” and “turn on a dime” both communicate an abrupt change of direction or speed. With the DIME model (Figure 1; adapted from Louis et al., 2020, p. 60), our goal was to consider the volatility of collective action, and to put forward the idea that failure diversifies social movements because the collective actors diverge onto distinct and mutually contradictory trajectories. Specifically, the DIME model proposes that after success collective actors generally persist in the original tactics. After failure, however, some actors would Disidentify (losing commitment and ultimately leaving a group). Others would seek to Innovate, leading to trajectories away from the failing tactics that could include radicalisation and deradicalisation. And a third group might double down on their pre-existing attitudes and actions, showing Moralisation, greater moral urgency and conviction, and Energisation, a desire to ramp up the pace and intensity of the existing tactics. We think these responses can all co-occur, but since they are to some extent contradictory (particularly disidentification and moralization/energization), the patterns are often masked within any one sample. They can be teased apart using person-centered analyses that look for groups of respondents with different associations among variables. Another approach could be comparing different types of participants (like people who are more and less committed to a cause) where based on past work we would expect that all three of the responses might emerge as distinct. The disidentification trajectory – getting demotivated and dropping out – has been understudied in collective action, and for groups more broadly (but see Blackwood & Louis, 2012; Becker & Tausch, 2014). A major task for leaders and committed activists is to try to reduce the likelihood of others’ disidentification by creating narratives that sustain commitment to the group in the face of failure. Inexperienced activists, those with high expectations of efficacy, and those with lower levels of identification with the cause may all be more likely to follow a disidentification or exit path. Some that drop out, furthermore, may develop hostility towards the cause they left behind. A challenge for the movement therefore is to manage the bitterness and burnout of former members. The moralization/energization path is likely to be the default path for those who were more committed to the group. In the face of obstacles, these group members will ramp up their commitment. But for how long? Attributions regarding the reason for the failure of the initial action are likely to influence the duration of persistence, we suspect: those with beliefs that the movement can grow and would be more effective if it grew may stay committed for a longer time, for example. In contrast, attributions that failures are due to decision-makers’ corruption or opponents’ intractability may lay the groundwork for taking an innovation pathway. A challenge for the leadership and movement is to understand the reasons for the movement failures as they occur, and to communicate accurate and motivating theories of change that sustain mobilisation. Finally, the innovation path as we conceive it may lead from conventional to radical action (radicalisation), or from radical back to conventional (deradicalisation). It may also lead away from political action altogether, towards more internally focused solidarity and support for ingroup members, or towards movements of creative truth-telling and art. There may be individual difference factors that promote this pathway, but it is also a direction where leadership and contestation of the group’s norms would normally take place, as group members dispute whether the innovation is called for and what new forms of action the group should support. The DIME model aims to answer the call to theorise about the volatility of collective action and the dynamic changes that so clearly occur. It also contributes to a growing body of work that is exploring the nature of radicalisation and deradicalisation. We look forward to engaging with other scholars who have a vision of work in this space. - By Professor Winnifred Louis

0 Comments

Recently, some states in Australia have begun considering the implementation of a law criminalising coercive control. Similar laws were recently introduced in England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland. So what should you know about the criminalisation of coercive control? 1. What is coercive control? Although the behaviours that constitute coercive control have long been recognised by researchers in domestic abuse, the term coercive control was first coined by Evan Stark in 2007. Coercive control covers a wide range of behaviours used to dominate and control the victim including:

2. Why do supporters want to criminalise coercive control? Given the pervasive nature of these sorts of abuse, it is perhaps unsurprising that many would like to see these behaviours criminalised. As the law in Australia currently stands, many coercive control behaviours can be very difficult to prosecute. Because the system currently takes an episodic approach to domestic violence and abuse, and relies on an intent to cause harm, individual incidents need to be viewed as intentionally harmful criminal events in order for the court system to charge the offender. However, this approach has limitations. Firstly, unlike most crimes (e.g., theft) domestic abuse is cumulative. This means that a seemingly minor individual incident might be harmful when experienced as part of a pattern of ongoing behaviours. Often it is the repeated victimisation that causes lasting harm. Additionally, some abusers may not intend to cause harm but simply believe that their victim’s behaviour needs to be altered. This belief does not however, negate the harm caused. Secondly, there are cases where a victim of abuse may resist their abuser in a verbal or physical altercation. In these cases, the incident-based approach can lead to charges being brought against the victim. Supporters of the new law argue that criminalising coercive control would allow evidence from outside of the specific incident to be brought forward, potentially protecting victims against being miscategorised as perpetrators. Recognising what is and is not abuse is often challenging and contested. New coercive control laws would help to send a clear message that these behaviours are abusive and therefore, unacceptable. 3. Why do detractors have concerns? If criminalising coercive control has the potential to do so much good, why are some people against this proposed law? Those opposed to criminalising coercive control have several key concerns. However, opposition generally reflects concerns regarding the implementation and application of the law rather than the spirit in which it is intended. Firstly, there needs to be a concrete way to inform victim/survivors of the existence of the coercive control law, and how it might be of use to them. There must also be education for law enforcement officers and first responders. Many are concerned that even if victims/survivors wish to use this law, if the offence is implemented without accompanying shifts in perspective from the first responders, law enforcement, and all others involved in the legal system, then outcomes will not change optimally for victim/survivors. Further, without victim supportive attitudes from all those involved in the legal system, some worry that a coercive control offense will become another avenue for abusers to use the courts and the law to further their abuse. Legal cases can be a public platform for perpetrators to undermine and humiliate their victim, attacking their character, every decision they have made, and every aspect of their life. Additionally, trauma can impact memory and recall. Because of this, the person who presents the most coherent story may often be the abuser, someone typically practised in the art of manipulation. Some believe that this law runs the risk of being diverted to the prosecution of victims, particularly if the victim has resisted their abuser on several occasions. Finally, it is important to note that the legal system is not right for everyone. Some victim/survivors may not feel that bringing a legal case against their abuser is worth the risk of possible retaliation, whilst others may simply not want to go through a court case where they will be forced to relive their trauma. It is essential that implementation of a coercive control law does not detract from other responses to abuse such as counselling programs for victims and perpetrators (whether they separate or remain together), housing assistance for victim/survivors, and support for survivors and their families to help them escape their abusers. Closing thoughts Criminalising coercive control has potential to be a step in the right direction. However, any attempts to implement such a law should be carefully considered, with every effort made that the implementation of criminalising coercive control benefits victims. To learn more about coercive control, you can access resources here and here. - By Kiara Minto Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you’ve probably heard that there is a crisis of confidence in the charity sector. In recent years a series of high-profile scandals have rocked the sector, including the Oxfam sexual exploitation scandal and the suicide of an elderly British donor Olive Cooke, who had received an estimated 3,000 charity appeals in the year before her death. Scholars, practitioners, and the media have lamented falling trust in charities and worried about the ramifications for the nonprofit sector. Trust is known to be an essential ingredient for fundraising success. Drops in charity confidence could therefore threaten the survival of the sector as a whole. My colleagues and I study charity scandals and trust in nonprofits. Through a series of experiments, we have demonstrated that scandals emerging within nonprofits have dire consequences for transgressing organizations. In fact, nonprofits lose trust and consumer support at faster rates after a scandal than commercial organizations do. It’s clear that scandals damage trust in particular organizations. But do highly publicized scandals also damage trust in the sector as a whole? To answer this question, we accessed global data collected as part of the Edelman Trust Barometer. Each year, Edelman survey people around the word and ask, among other things, how much they “trust NGOs in general to do what is right”. Edelman shared data from 294,176 people in 31 countries over a period of 9 consecutive years. We analyzed these data in a way that had not been done before. Specifically, we looked at trust trends after taking into account individual differences (i.e., the fact that some kinds of people are more or less trusting) and country differences (i.e. the fact that some countries are generally more or less trusting and that different countries may show different trust trends over time). Spoiler: There is no global crisis of trust in nonprofits Our analysis shows no significant decrease in trust over time. In fact, once we accounted for individual and country differences, trust in NGOs has actually increased slightly around the globe between 2011 and 2019. It’s true that some people and countries show different trends. For example, the increase in trust was sharper among men, people aged under 40 years, and people with higher education, income, and media consumption. Although some countries showed small increases and some showed small decreases in trust, none of these trends was substantial in size. In other words, there is no was no evidence that trust in NGOs has changed meaningfully in any of the 31 countries over the last decade. So why do the public still trust nonprofits despite the scandals? The short answer is we don’t know. The data allowed us to identify if trust was changing over time but not why. We have some ideas about what might be going on though. Charities, generally speaking, have reputations for being moral. We suspect that this good reputation functions as a kind of “trust bank” that buffers charities from the effects of scandals. Perhaps over time the sector makes deposits in the community trust bank through their good works in society. When scandals emerge within individual organizations, this may draw down some of the community trust that has built up over time but have very little impact on reserves of trust in the overall sector. What does this mean for nonprofit managers? If the good deeds of charities cultivate trust banks from which they can safely draw on in times of crisis—an idea that has not yet been evidenced—then a key strategy will be to ensure all successes are communicated both to the supporter base and to the wider public. Nonprofit leaders should also encourage other organizations within the sector to do the same. When the nonprofit sector works together to highlight their good works, the entire sector may benefit in the future when unexpected scandals erupt within the community. - Dr Cassandra Chapman *** This article was reposted with permission from the NVSQ Blog. Read the full article: Chapman, C. M., Hornsey, M. J., & Gillespie, N. (2020). No global crisis of trust: A longitudinal and multinational examination of public trust in nonprofits. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. doi: 10.1177/0899764020962221 |

AuthorsAll researchers in the Social Change Lab contribute to the "Do Good" blog. Click the author's name at the bottom of any post to learn more about their research or get in touch. Categories

All

Archive

July 2024

|

Social Change Lab

Join our mailing list!Click the button below to join our mailing list:

Social Change Lab supports crowdfunding of the research and support for the team! To donate to the lab, please click the button below! (Tax deductible receipts are provided via UQ’s secure donation website.) If you’d like to fund a specific project or student internship, you can also reach out directly!

|

LocationSocial Change Lab

School of Psychology McElwain Building The University of Queensland St Lucia, QLD 4072 Australia |

Check out our Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2017

RSS Feed

RSS Feed