|

The Amazon is the largest and most biodiverse tract of tropical rainforest in the world, home to roughly 10% of the world species. It’s also the world’s largest terrestrial carbon dioxide sink and plays a significant role in mitigating global warming. While forest fires in this region are frequent occurrences, and typically happen in dry seasons due to illegal slash-and-burn methods that are used to clear forest for agriculture, livestock, logging and mining, the 2019 wildfires season was particularly devastating. In 2019 alone, estimates suggest over 10 000 km2 of forest within the Amazon biome was lost to the fires with August fires reaching record levels. Destruction of the Amazon doesn’t just threaten increasingly endangered species and the local indigenous populations. As the amount of carbon stored in the Amazon is 70 times greater than the annual US output of greenhouse gases, releasing that amount of extra carbon into the atmosphere would undo everything society has been doing to reduce emissions. Deforestation of the Amazon fluctuates alongside the political landscape of Brazil. Between 1970 and 2005, almost one-fifth of the Brazilian Amazon was deforested. In the 2000s, President Lula da Silva implemented programs to control deforestation, which reduced deforestation by 80% by 2012. Jair Bolsonaro took office in 2019, scaling back the Amazon protections and regulations in hope of stimulating economic growth, which led to a 30% increase in deforestation over the previous year. The international community was understandably displeased; verbal condemnations were made and aid payments to Brazil were cut. However, for the poor populations living in and around the Amazon, it’s about survival. Clearing land gives an immediate economic benefit in the form of cattle ranching, even if it’s an inefficient place to farm cattle due to its distance from potential markets and poor soil quality. If money is the driver of deforestation, perhaps money will offer the solution. The landholders in Brazil could be compensated to forego the profits from converting forests to cattle. There are precedents for such environmental programs, a notable example was China’s Grain for Green program in 1999 – the world’s biggest reforestation program – in which120 million households were paid what amounted to about $150 billion over a decade to protect existing forest or restore forest. In 1996, the Costa Rica government introduced the Payments for Environmental Service (PES) to pay landowners to protect or restore rainforest on their property. With a payment of $50 per hectare, it was enough to slow and reverse deforestation rates. By 2005, Costa Rica’s forest cover has increased by 42% from when the program began. Brazil is also warming up to this idea. One such initiative is the “Adopt a Park” program, announced last month in Brazil, which will allow national and international funds, banks and companies to pay to preserve areas equivalent to 15% of Brazil’s portion of the Amazon – an area larger than Chile. However, for such programs to succeed and attract international support, the Brazilian government would need to demonstrate their ability to stop illegal loggers and wildcat miners from decimating the landscape.

There already exists an appetite for these conservation schemes among world leaders. Norway was willing to provide roughly $100 million per year over a decade to support a non-profit dedicated to reducing Amazon deforestation. In a debate with Bernie Sanders, Joe Biden, the Democratic nominee for president expressed similar sentiment: I would be right now organizing the hemisphere and the world to provide $20 billion for the Amazon, for Brazil no longer to burn the Amazon. These cash-for-conservation schemes might seem like handouts, but it is high time the world’s biggest polluters pay their dues. The Western bloc is responsible for around half of the global historical emissions (the US – 25%, the EU – 22%). Those who will suffer the most acutely from the consequences of climate change are also the least responsible – the poorest of the poor and those living in island states: around 1 billion people in 100 countries. There is a significant ecological debt owed to low-income nations from industrialized first-world nations for the disproportionate emissions of greenhouse gases. Now that the impacts of climate change are unavoidable and worsening, investment in adaptation to rising temperatures and extreme weather is more important than ever. In the drive to better humankind and amass wealth for a few, we’ve wreaked havoc on the world’s environment and put the lives and livelihoods of many in jeopardy. Now it is time for those of us in the West to use our plenitude of wealth, knowledge and technology to help those in need, and to mitigate and prepare for the consequences of our actions.

0 Comments

From reduced air pollution to cleaner water, the COVID-19 pandemic has provided a vision of hope: evidence that we are capable of rapidly changing our behaviours to build a cleaner, healthier environment. However, what is less clear is whether this vision can be translated into reality. To help investigate this question, the Network of Social Scientists convened an online workshop in late May. The group of around 30 academics and environmental professionals pooled their expertise to explore the effects of the pandemic on the environment. Through investigating the following three questions they identified a range of impacts and barriers to change, as well as techniques for sustaining positive outcomes as the lock downs ease. What have been the environmental impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic? A diverse range of positive and negative environmental effects were highlighted by NESS experts. Many enforced changes from the lock downs led to environmental benefits: more cycling, gardening and engagement in green spaces, a reduction in food waste and greater support for local businesses and food chains were all suggested. In the workplace, a remarkable transition to an online world challenged the dominance of in-person meetings and international travel, both reducing environmental impacts and increasing accessibility and connectivity. Attitudes may have also changed. Trust in experts was enhanced by the centrality of health experts on daily news reports and other media. Some workshop participants believed more positive attitudes towards our ability to create change had emerged, which could flow onto increased mobilization against climate change. Our ability to collectively shoulder immense economic risks to safeguard our health proved that politics can produce results in times of crisis. Some argued that this has shown that the ‘behaviour change barrier’ can be broken. However, as many social scientists noted, behavioral changes are likely to slide as we slowly return to past habits. As well as this concern, NESS experts highlighted the range of negative environmental impacts which were resulting from the pandemic. The drowning out of attention on bushfires and climate change, the continued practice of ‘ghost flights’, a surge in internet and energy use, and the quadrupling of medical waste indicated a high level of doubt about whether any longer term positive environmental benefits will be sustained. What barriers may prevent our ability to sustain positive environmental effects? The UN Secretary General António Guterres hoped that 2020 would be a pivotal year for addressing climate change. Yet despite the horror of the 2019/20 Australian bushfires, media and political attention swiftly re-focused on the pandemic. As the economic and social costs of the pandemic built, NESS experts noted how political barriers resisting change may once again reassert themselves. The renewed focus on development and jobs might serve as a reason or excuse to cut environmental funding, projects and regulations aiming to protect the environment as has happened in previous economic downturns. The prioritization of a gas led recovery indicates limited political support for a fast transition to clean energy. While calls for an Australian ‘green new deal’ are growing, countering the desire to strip back environmental regulation will require a sustained and powerful collective response. As work and holidays returns to pre-pandemic habits, emissions and other negative environmental impacts resulting from commuting and travel may rapidly rise. Turning changed attitudes and behaviours into habits will likely be difficult. A 50% increase in household waste managed by Australian Councils were foreseen by NESS experts. Pivoting back to eco-friendly behaviours such as public transportation use will be likely be discouraged. The surge in use of public green spaces in wealthier nations could be offset by increased deforestation and biodiversity loss in the Global South as newly unemployed migrant workers return to villages to survive. The economic shock of a recession may reduce public support for implementing environmentally beneficial policies. There are myriad localized and personal barriers which may make sustaining environmental positive behaviours much harder to maintain. What insights from social science can help leverage COVID-19 to achieve positive outcomes for the environment? NESS experts suggested three techniques which could be used to overcome the barriers which will drive a return to ‘business as usual’ as our communities emerge from lock down. First, there is evidence from past pandemics that highlighting the positive personal benefits of changed behaviours can spur lasting change. Past pandemics using this frame drove the development of more green spaces, enabling healthier urban environments alongside increased access to nature. Organisations seeking to advocate for permanent post-pandemic changes could seek to frame their messages referencing the personal benefits of clean air and quieter cities, the benefits to health and personal safety, and the financial and time savings to people and firms from reduced travel costs. Second, NESS experts highlighted the value of capitalising on the momentum we have already built in achieving short term changes. Research on dynamic or change norms highlights that the mere knowledge that a growing number of others have been doing a certain behaviour will increase intentions to adopt that behaviour. Third, NESS experts recommended the use of trusted messengers to communicate about environmental change. Celebrate local businesses cementing in more sustainable post-COVID-19 practices. Capitalize on the increased profile of health experts by amplifying messages from groups such as Doctors for the Environment. Work from within organisations to accelerate change and demonstrate the value of a cleaner and healthier world. COVID-19 has powerfully demonstrated the differences in the power of trusted leaders and voices to mobilise, compared to contested or outsider voices. Already the environmental effects of the pandemic have begun to be documented through a range of academic papers and opinion pieces. Whether for good or ill, the pandemic has shown us that we do have the power to change the impact we have on the world. The challenge is now to build a new reality from this brief moment of hope. The summary report from the workshop is available here. - By Dr. Robyn Gulliver This article was originally posted by NESSAUSTRALIA (Network of Environmental Social Scientists). You did, so you can, and you will – how self-efficacy guides adoption of difficult behaviour.29/6/2020 How can people become more environmentally sustainable? One theory that describes how human behaviour may be influenced is behavioural spillover. Spillover is the notion that doing one behaviour triggers adoption of other behaviours. It’s the idea that engaging in certain behaviours can put you on a ‘virtuous escalator’, where you keep doing more and more. Spillover has grabbed the attention of researchers and policy makers since it offers a cost-efficient, self-sustaining form of behaviour change that when understood properly could be harnessed for fostering the adoption of desirable behaviour. Spillover as a concept is intuitive, since it ‘makes sense’ that one behaviour may influence another. Yet spillover as a phenomenon is far more elusive than intuitive, since there are a growing number of studies with mixed findings about whether or not spillover occurs. The important question within spillover research these days is “how can spillover be encouraged?” We were interested in one particular mechanism: self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is the belief that you are capable enough to be able to do a certain behaviour. We were interested in self-efficacy as a spillover mechanism since it is theorised to have a bi-directional relationship with behaviour. Self-efficacy is influenced by what you have done in the past and self-efficacy influences what you choose to do in the future (known as reciprocal determinism).

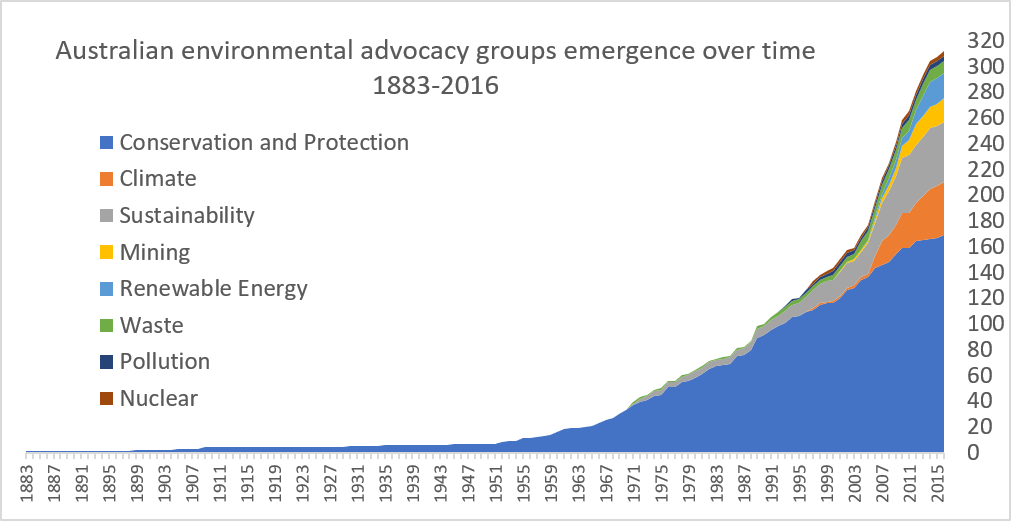

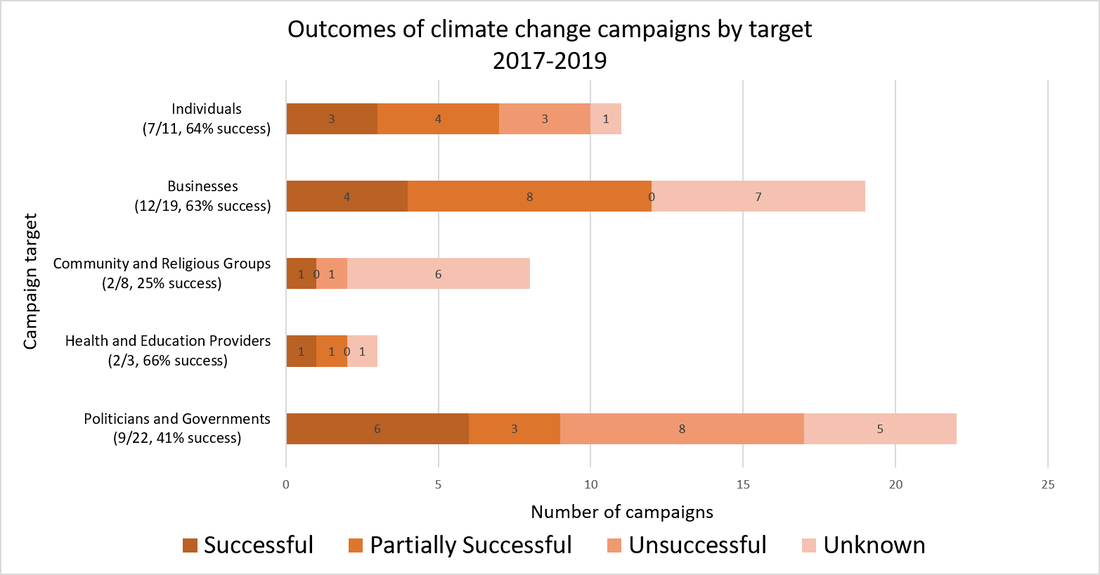

Across 2 studies with Australian participants, we explored whether self-efficacy may be a potential mechanism for fostering behavioural spillover. In the first study, information was gathered on participants’ past engagement and intended engagement in 10 water-related behaviours (i.e., behaviours that influence water use, such as water conservation/efficiency and water quality protection behaviours). A pilot study showed that 6 of these behaviours were considered ‘easy’ to do and 4 were considered ‘difficult’ to do. We also measured participants’ sense of self-efficacy towards protecting water quality and conserving water (e.g., I feel confident I can engage in ways to protect water quality). We found that the easy behaviours people have done in the past were related to their sense of self-efficacy, and this greater sense of confidence was associated with increased intentions for more difficult behaviour in the future. These findings were exciting, but two questions remained: 1) is self-efficacy a consistent spillover mechanism? E.g., can we find the effect again? And 2) can this effect lead to actual behaviour? To answers these questions, we used data collected over two occasions with Australian householders that reported whether they were participating in certain water-reducing behaviours and had installed water efficiency devices (e.g., water tank, water efficient washer). Similar to the findings of Study 1, we found that the more water reduction behaviours (i.e., easy behaviours) householders had adopted, the greater their self-efficacy, and the greater their intentions for installing water efficiency devices (i.e., difficult behaviours), in turn, the more of these water efficient devices were actually installed. In lay peoples’ terms, we found that the easy things people had been doing fed into their self-efficacy, which increased their intentions and actual adoption of more difficult behaviour. Ultimately these findings demonstrate support for the idea that self-efficacy may be a mechanism that encourages spillover. These two studies demonstrate associations between past behaviour, self-efficacy, and intended and actual future behaviour, shedding some light on a potential mechanism of spillover. Further testing in real-world settings is needed to understand if self-efficacy can be harnessed and used to inspire adoption of more impactful behaviour. What these findings do suggest is that “from little things, big things grow”! The things we do, even if they are easy and simple, help us to gain the confidence to take on more difficult behaviours in the future. - By Nita Lauren Lauren, N., Fielding, K. S., Smith, L., & Louis, W. R. (2016). You did, so you can and you will: Self-efficacy as a mediator of spillover from easy to more difficult pro-environmental behaviour. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 48, 191-199. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.10.004 Problems within our global and interconnected food systems can result in outbreaks of infectious disease spread by bacteria, viruses, or parasites from non-human animals to humans. This is also known as zoonosis. The swine flu pandemic of 2009, for example, was caused by a hybrid human/pig/bird flu virus that originated from dense factory farms where pigs and poultry were raised in extremely cramped conditions together. Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), a bacteria that results in more deaths in the US than HIV/AIDS, also has strong causal link to factory pig farms. SARS-CoV-2, the virus behind the current COVID19 pandemic, may have developed in bats and later pangolins. Both species are regularly hunted for food and medicinal purposes and are sold in wet markets. Wet markets, where live animals comingle in unsanitary conditions provide the perfect environment for diseases to migrate between animals and people. Zoonosis is just one of the many threats posed by the expansion of our food system to global public health. Globally, 72% of poultry, and 55% of pork production come from concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs), or factory farms. For example, chicken CAFOs can hold up over 125,000 chickens. The close quarters and high population inside CAFOs allow the sharing of pathogens between animals with weakened immune systems. Thus, diseases spread rapidly. To safeguard their stock, CAFOs inject low doses of antibiotics into feed. This is intended to lower chances of infection, and conserve the energy animals expend to fight off bacteria in order to promote growth. This method is not without problems; antibiotics are usually administered to whole herds of animals in feed or water, which makes it impossible to ensure that every single animal receives a sufficient dose of the drug. Additionally, farms rarely use diagnostic tests to check whether they are using the right kind of antibiotic. Thus, every time an antibiotic is administered, there is a chance that bacteria develop resistance to it. Resistant bacteria can then pass from animals to humans via the food chain, or be washed into rivers and lakes. Also, bacteria can interact in the farm or in the environment, exchanging genetic information, thus increasing the pool of bacteria that is resistant to once-powerful antibiotics. Due to global trade of meat and animal products, these resistant bacteria can spread rapidly across the globe. A study sampling chicken, beef, turkey, and pork meat from 200 US supermarkets found 20% of samples contained Salmonella, with 84% of those resistant to at least one antibiotic. Another study tested 136 beef, poultry and pork samples from 36 US supermarkets and found that 25% tested positive for resistant bacteria MRSA. Fortunately, in both cases these bacteria can be eliminated with thorough cooking. Nevertheless, more than 2.8 million antibiotic-resistant infections occur in the U.S annually, resulting in more than 35 000 deaths. While antibiotic resistance has been a known issue for some time, policy responses have been mixed. The European Union has prohibited the use of antibiotics to promote growth in animals since 2016. Other parts of the world have been more lax, with nearly 80% of all the antibiotics dispensed in the US fed to livestock, and only 20% on humans. Here at home in Australia, we have one of the most conservative approaches, ranked the 5th lowest for antibiotic use in agriculture among the 29 countries examined. The factory farm system is a modern answer to a modern problem -the rapid rise in global population and demand for meat. While the economies of scale allow factory farms to be more cost-efficient and more competitive in a very crowded market, these come at the expense of every other living thing involved. Further, as our demand for meat is projected to continue rising, so will the issues associated with factory farms: environmental damage from toxic waste pollution, poor animal welfare, the exacerbation of climate change, and poor working conditions. Last year, US Senator Cory Booker unveiled the US Farm System Reform Act of 2019. One proposal from the Bill is to shut down large industrial animal operations like CAFOs. While the Bill is unlikely to pass the Republican-controlled Senate and White House, it signifies the growing public awareness of the wide-ranging problems associated with our food systems. Reducing our meat consumption also comes with personal health benefits, and reduces animal suffering, in addition to reducing the demand for factory farming and the associated health risks. That is not to say a change in dietary habit is without its barriers. Factors such as socio-economic status, access to food, and existing health problems will prevent many from drastically reducing their meat consumption. At the end of the day, our best is all we can do, but as more of us begin taking steps, however small, towards changing our diets, we will make a difference. - By Hannibal Thai *Special thanks to Ruby Green for her assistance in the writing of this post. Every day most of us reap the benefits of collective action undertaken in the past by others. Momentous upheavals play out over centuries as the rights of some and duties of others change in tempo with changing norms and laws. We have seen this play out through history as legal slavery is abolished, disability rights are protected, and demands for Indigenous sovereignty grow. These changes ebb and flow at the macro level, the viewpoint we use to understand changes in society at large. But how do we know what the actual forces of social change are? We must understand the meso-level dynamics of groups, communities and institutions, or investigate even deeper into the micro-level influences on social change fueled by individuals and their activities. Delving into this micro world of activism is how I spent the first year of my PhD. New technologies have enabled digital humanities researchers to gather large empirical databases to investigate the characteristics of social change at the group and individual level. I used these technologies to capture what environmental movement groups and their members are doing, where they are doing it, and what they are achieving. Our findings have been published in two journal articles. Our first paper published in Environmental Communication - The Characteristics, Activities and Goals of Environmental Organizations Engaged in Advocacy Within the Australian Environmental Movement - uses data captured through a content analysis of 497 websites to show how active environmental advocates are. With over 900 campaigns and thousands of online and offline events, they have been busy advocating for environmental care for more than a hundred years. Furthermore, most of their efforts are not radical, with activists predominantly working as volunteers in our local communities with the aim to increase awareness and understanding about more pro-environmental behaviors. But activity is one thing; outcomes are another. We wanted to know whether this activity is successfully effecting change. To investigate, we went back to the micro level to ascertain the outcomes of climate change campaigns. The causes of climate change are intractable, diffuse, and woven into the fabric of our social, political and economic systems. So how do activist groups try to stop climate change, and is any one way more successful than the others? Our findings were published in the paper ‘Understanding the outcomes of climate change campaigns in the Australian environmental movement’ in the journal Case Studies in the Environment. We identified the target and goal of 58 campaigns specifically focusing on climate change and tracked their outcomes over a 2-year period. Some of these campaigns aimed to stop new coal mines. Some of them wanted government to enact new climate policies. Our data showed that almost half of these campaigns either fully or partially achieved their goal. For example, coal mines were delayed, and climate policy was enacted. In particular, 63% of campaigns asking individuals, businesses and health and education providers to reduce their climate impact were either partially or fully successful. In total 49% of all campaigns achieved full or partial success. These campaigns each only focus on one small piece of the solution to climate change and we cannot be sure how much campaign activities directly influence outcomes. Yet our research using real-world data shows that these environmental groups are connected to, and likely playing a crucial role in driving meaningful change which will help protect the environment. These activities constitute the incremental successes and failures which together drive social change. - By Robyn Gulliver Consider this troubling fact: an analysis of blogs that focus on denying climate change found that 80% of those blogs got their information from a single primary source. Worse, this source—a single individual who claims to be a “polar bear expert”—is no expert at all; they possess no formal qualifications and have conducted no research on polar bears. No matter what side of the debate you are on, this should concern you. Arguments built on false premises don’t help anyone, regardless of their beliefs or political leanings. But does this sort of widespread misinformation—involving the mere repetition of information across many sources—actually affect people's beliefs? To find out, we asked research participants to read news articles about topics that involved different governmental policies. In one experiment, participants read an article claiming that Japan’s economy would not improve, as well as one or more articles claiming the economy would improve. Unbeknownst to our participants, they were divided into three groups. The first group read four articles claiming the economy was going to improve—and importantly, each of these articles cited a different source. The second group read the same four articles, except in this case, all of the articles cited the same source (just like the climate-change-denying blogs all cite the same “expert”). And to establish a point of comparison for the other groups, the third group of participants read just one article claiming the economy would continue to improve. You might expect that when information is corroborated by multiple independent sources, it is much more likely to sway people’s opinions. If this is the case, then people who read four articles that each cited a unique source should be very certain that Japan’s economy will continue to improve. Furthermore, if people pay attention to the original sources of the information they read, then those who read four articles that all cited exactly the same source should be less certain (because that information was repeated but not corroborated). And, finally, people who read only one article claiming Japan’s economy will improve should be the least certain. Indeed, people were much more likely to believe that Japan’s economy would improve when they heard it from four unique sources than when they read only one article. But, surprisingly, people who read four articles all citing the same source were just as confident in their conclusions. Our participants seemed to pay attention only to the number of times the information was repeated without considering where the information came from. Why? Perhaps people assume that when one person is cited repeatedly, that person is the one, true expert on that topic. But, in a follow-up study, we asked other participants exactly this question: all else equal, would you rather hear from five independent sources or one single source? Unsurprisingly, most believed that more sources were better. But here's the shocking part: when those same participants then completed the task described above, they still believed the repeated information that all came from the same source just as much as independently sourced information—even for those who had just said they would prefer multiple independent sources. These results show that as we form opinions, we are influenced by the number of times we hear information repeated. Even when many claims can be traced back to a single source, we do not treat these claims as if we had heard them only once; we act as if multiple people had come to the same conclusion independently. This “illusion of consensus” presumably applies to virtually all the information that we encounter, including debates about major societal issues like gun control, vaccination, and climate change. We need to be aware of how simple biases like these affect our beliefs and behavior so that we can be better community members, make informed voting decisions, and fully participate in debates over the public good. We wanted to finish this article with a fun fact concerning the massive amount of information that people are exposed to each day. So, we asked Google: "How much information do we take in daily?", and we got a lot of answers. Try it for yourself. You'll see source after source that says you consume about 34 gigabytes of information each day. You may not know exactly how much 34 gigabytes is, but it sure sounds like a lot, and several sources told you so. What's the problem? All of these sources circle back to a single primary source. And, despite our best efforts, we weren't able to find an original source that was able to back-up these claims at all. If we weren't careful, it would have been easy to step away believing something that might not be true—and only because that information was repeated several times. So, next time you hear a rumor or watch the news, think about it. Take one moment and ask, simply, "Where is this information coming from?" - By Sami Yousif, Rosie Aboody, and Frank Keil Sami Yousif is a graduate student at Yale University. His research primarily focuses on how we see, make sense of, and navigate the space around us. In his spare time, he also studies how we (metaphorically) navigate a world of overabundant information. Rosie Aboody is a graduate student at Yale University. She studies how we learn from others. Specifically, she’s interested in how children and adults decide what others know, who to learn from, and what to believe. Frank Keil is a professor of psychology at Yale University and the director of the Cognition and Development lab. At the most general level, he is interested in how we come to make sense of the world around us. This post is previously published on the Society of Personality and Social Psychology; Character and Context Blog For Further Reading: Yousif, S. R., Aboody, R., & Keil, F. C. (2019). The illusion of consensus: a failure to distinguish between true and false consensus. Psychological Science, 30, 1195-1204. I want to start by acknowledging our group’s successes In 2019, the lab saw Tracy Schultz and Cassandra Chapman awarded their PhD theses (whoohoo!). Tracy Schultz is working grimly but heroically in the Queensland department of the environment and Cassandra Chapman spent a year as a post doc in UQ’s Business School before securing a continuing T&R position there. Well done to both! It was also great fun welcoming Morgana Lizzio-Wilson as a post doc off our collective action grant (and hopefully continuing to work on the voluntary assisted dying grant in 2020): Morgana brought lots of vital energy to the lab, and I’m very grateful. 2019 also saw many other students working through their other milestones, including Hannibal, Liberty and Robin who were successfully confirmed (huzzah!), and Gi, Zahra, Kiara, Susilo, and Robyn who pushed through mid-candidature reviews and are coming up to thesis reviews. I also welcomed a new PhD student, Eunike Mutiara, who is working with Annie Pohlman in the School of Languages and Cultures at UQ on a project in genocide studies (I am an Associate Advisor). We had big health drama, with me and Tulsi both spending a lot of time away from work due to health concerns. Here’s hoping 2020 is healthy, happy and productive for us and for the group! I also want to pass on a special thank you to our volunteers and visitors for the social change lab in 2019, including Claudia Zuniga, Vladimir Bojarskich, Hema Selvanathan, Jo Brown, Tarli Young, Sam Popple, Michaels White, Dare, and Thai, Elena Gessau-Kaiser, Lea Hartwich, and Eleanor Glenn. Thank you everyone! And here’s hoping that 2020 is equally fun and social! Other news of 2019 engagement and impact With our normal collective plethora of conference presentations and journal articles (see our publications page for the latter), I continued to have great fun this year with engagement. In the environment space, I gave a few talks to universities but also state environment departments and groups such as the WWF (World Wildlife Fund). The talks argue that environmental scholars, leaders and advocates need to develop an understanding of the group processes underpinning polarisation and stalemates, because this is the new frontier of obstacles that we are facing. I reckon many established tactics of advocacy don’t actually work as desired to create a more sustainable world. We need to focus on those that avoid polarisation and stalemates, and instead grow the centre and empower conservative environmentalists. We should use evidence about effective persuasion in conflict to try to improve the outcomes of our advocacy and activism. As the year turns and the bush fires burn, as the feedback loops become more grimly clear in the oceans, ice caps, and rain forest, and as the global outlook looks worse and worse, I feel there is more appetite for new approaches among those environmental scientists, policy makers, and activists who are not drowning in despair and fury. J To mitigate despair and fury, I draw attention to new work by Robyn Gulliver coming out re what activists are doing and what successes they are obtaining. I also see a continued and increasing need for climate grief and anxiety work and I draw attention to the excellent Australian Psychological Society resources on this topic. Looking at radicalisation and extremism: thanks to the networks from our conference at UQ last year on Trajectories of Radicalisation and Deradicalisation, I was invited to a groovy conference on online radicalisation at Flinders organised by Claire Smith and others. I reconnected with many scholars there, plus meeting heaps more at the conference and at the DSTO (the defence research group) in Adelaide. I am looking forward to connecting more widely - the interdisciplinary, mixed-methods engagement is exhilarating. It was also excellent at the conference to see the strong representation from Indonesian scholars like Hamdi Muluk, Mirra Milla and their colleagues and students. There is a lot to learn from their experience and wisdom, and I am excited to visit Indonesia this year. Also on extremism, as part of my sabbatical, I visited the conflict centre at Bielefeld led by Andreas Zwick, with Arin Ayanian and others. It was truly impressive to see their interdisciplinary international assembly of conflict and radicalisation researchers, including refugee scholars sharing their expertise. I wish there were more of a consistent practice of translating the German-language output though eh. (Is it crazy to imagine a crude google translate version posted on ResearchGate, or at a uni page?) J I also visited Harvey Whitehouse’s group at Oxford, and greatly enjoyed the opportunity to give a talk at the Centre for the Study of Social Cohesion and to meet some of his brilliant students and post docs. And at St Andrews, Ken Mavor and Steve Reicher put together a gripping one day symposium on collective action: it is exciting to see the new Scottish networks that are coming together on this topic. On the sabbatical so far, I also visited Joanne Smith at Exeter, Linda Steg and Martijn van Zomeren at Groningen, Catherine Amiot at UQAM, Richard Lalonde at York, Jorida Cila and Becky Choma at Ryerson, and earlier Steve Wright and Michael Schmidt at Simon Fraser. It is very fun to spend time with these folks and their students and colleagues, and I look forward to my 2020 trips, which are listed below. Just so people know, right now as well as trying to publish the work from the DIME grant on collective action (cough cough), I am trying to work up new lines of work on norms (of course!), (in)effective advocacy and intergroup persuasion, and religion and the environment. I welcome new riffing and contacts on any of these. In other news, our lab has continued to work to take up open science practices in 2019 and to grapple with the sad reality – not new, but newly salient! – that sooo many hypotheses are disconfirmed and so many findings fail to replicate. We are seeking further consistency in pre-registration, online data sharing, transparency re analyses, and commitment to open access. Looking at articles, though, it still seems extremely rare to see acknowledgement of null findings and unexpected findings permitted, and I think this is still the great target for reviewers and editors to work on in order to propel us forward as a field. Socialchangelab.net in 2020 Within the lab, Kiara Minto has been carrying the baton passed on by Cassandra Chapman, who started the blog and website in 2018, and Zahra Mirnajafi, who also worked on it in 2019. Thank you to Kiara and Zahra for all your great work last year with our inhouse writers, our guest bloggers, and the site! I also am still active for work on Twitter, and I hope that you will follow @WlouisUQ and @socialchangelab if you are on Twitter yourself. In the meantime, we welcome each new reader of the blogs and the lab with enthusiasm, and hope to see the trend continue in 2020. What the new year holds In 2020, for face to face networking, if all goes well, I’ll be at SASP in April in Auckland, and at SPSSI in June in the USA. Please email me if you’d like to meet up. I’ll also be travelling extensively on the sabbatical – to Chile, Indonesia, New Zealand, and within Australia to Melbourne, Sydney and Adelaide. I hope people will contact me for meetings and talks if interested. Due to the sabbatical until July, I won’t be taking on new PhD students or honours students this year, but welcome expressions of interest for volunteer RAs and visitors from July onward. I’m not sure that I have as much energy as normal, what with all the travel and health dramas, but I am focusing almost exclusively on writing, talks and fun riffing until the sabbatical ends in few months, so let’s not let the time go to waste. J In Semester 2 2020, I’ll be teaching Attitudes and Social Cognition, a great third year social psychology elective, so I’m looking forward to that too. All the best from our team, Winnifred Louis When reflecting on what social change and social movements look like, images of activists protesting and engaging in other acts of civil resistance likely spring to mind for most people. However, this isn’t the only way to be a change agent. There are a myriad of ways that people can aide social change without engaging in ‘traditional’ forms of activism. In fact, we can only maximise the impact and potency of social movements if we diversify our tactics and have people ‘fighting the good fight’ in different ways. Below, I outline five common change agent roles and their effectiveness in different domains of the social change process to highlight the varied and equally valuable ways we can all contribute. The Activist The term activist can generally be understood as a person participating in collective action to further a cause or issue. Here, I focus on people who operate outside of formal systems or institutions to call public attention to injustice and agitate for social change using conventional and, in some cases, more radical tactics (e.g. Extinction Rebellion protesters blocking off bridges and main roads). When conducted appropriately, these actions can increase public support and discussion of the social issue. However, these approaches can also reinforce stereotypes that activists are ‘extreme’ which, in turn, may deter collective action participation among observers. The Insider Although activists can advocate for change outside the system, oftentimes social change messages are better received from ‘insiders’ or people who belong to the same groups or institutions that activists are trying to influence. As criticisms are trusted more when coming from ingroup members, insiders can make social change messages more palatable to the target group and may, in some cases, be able to communicate activists’ messages and concerns in terms that the ingroup can understand and be swayed by. The Scholar The Scholar’s role is twofold: to conduct rigorous and ethical research about social issues (e.g. the prevalence and impact of discrimination, the existence of anthropogenic climate change); and share this knowledge to inform public understanding of and discussions about these issues. Scholars can be academics at universities, members of research organisations (e.g. OurWatch), or, in some cases, organisations that share data about the prevalence and impact of social problems (e.g. Children by Choice publishing reports about the prevalence of Domestic Violence among their clients seeking terminations). Scholars’ ability to uniquely access and share this information can help to inform the general public’s understanding of social problems, fight misinformation, convince relevant stakeholders about the importance of an issue, and proffer evidence-based solutions. Indeed, social justice research can be used to successfully challenge and dismantle institutional prejudice and foster transformative social change by informing public policy and interventions. The Teacher An oft-overlooked role in social change is that of the teacher: a person who can foster civic engagement through formal education (e.g. primary, secondary, and/or tertiary education) or informal education (e.g. service-learning opportunities). Formal, classroom based educational interventions promote engagement with political issues and voting, while service-learning increases interest and participation in community-based action. Further, educational interventions can also be used to reduce prejudice toward disadvantaged groups. Thus, taking an active role in shaping people’s understanding of politics and social issues can positively influence their attitudes and political participation. The Constituent Constituents, or the general public, are often the numerical majority in social movements. They can include people who are sympathetic to but not committed to participating in actions for social change, or people who disagree with and resist social change messages. Unsurprisingly, constituents can greatly sway the progress of social movements, in that the attitudes and values they choose to adopt or reject influence the outcomes of state and federal elections, the types of laws and policies that governments and industries support, and broader norms in society. Thus, constituents have the power to elect leaders who support social change, call out unfair treatment and subvert anti-egalitarian norms, and support organisations and brands that make ethical choices (e.g. cruelty free cosmetics). Perhaps most importantly, other changes agents must make a considered effort to ensure that constituents have the information and support they need to make informed decisions and use their civic, relational, and economic powers effectively. Moving Forward Although the number and nature of these roles will likely vary between movements and socio-political contexts, they represent the diverse yet equally important forms of change agent work that can enhance the impact and effectiveness of social movements. The question now is: what role(s) do you play? How can you harness your unique skills and forms of influence to aid social change? Regardless of your answer, remember that just because you haven’t attended a protest or blocked oncoming traffic doesn’t mean that you aren’t a change agent. - By Morgana Lizzio-Wilson Disruptive protests gain media attention. For many people, this media attention might be the first time they learn of a particular social or environmental movement. his tactic and resulting media coverage often prompt predictable responses from the public and officials. Why, some ask, are protestors blocking roads instead of standing on the pavement educating people? Why protest if they don’t have a solution? But herein lurks a pervasive misconception of what activism actually is. Acts of civil disobedience enable awareness of a movement to bubble to the surface of daily life because they are newsworthy. However, this media attention can mask the years of relentless campaigning which builds the scaffolding to sustain these moments of shock. This scaffold is the groundwork done by the foot soldiers of a movement. Work done day after day, year after year, labouring at the often unseen toil that is the bread and butter of activism: recruiting volunteers, educating people and creating solutions. These tactics aren’t newsworthy. And sometimes to activists, they may feel like failure, creating the justification for the emergence of radical action. Does that mean that this toil was futile? Or, as argued by Extinction Rebellion, that tactics are now only just beginning? Coordinated acts of civil disobedience do not emerge spontaneously from an empty well. Take the American civil rights movement. Yes, Rosa Park’s determination to hold her bus seat created an iconic moment which helped galvanise the movement towards its goals. However, Rosa Parks was a long-term activist who, for decades, fought relentlessly against school segregation, wrongful convictions of black men, and anti-voter registration practices. Many other people had, in fact, held bus seats before her. She was one of thousands, many of whom, like her, were on the verge of exhaustion after perceiving that their years of activism had produced little change. We could look at any moment of newsworthy radical action and find parallels. Take the Salt March, an iconic moment of disobedience is now inextricably linked to the success of the Indian Independence movement. Organised as a defiant act against British rule in India, it was however, just one of the many tactics used in the 90 long years of struggle. Here in Australia, recent acts of civil disobedience for climate change action have emerged from a rich and vibrant foundation of environmentalism. Thousands of groups have been running thousands of campaigns across an array of issues. Activists have engaged in radical action against mining, logging and other destructive environmental practices for many years, using a diverse range of tactics for their cause. What were these tactics? Building groups, training volunteers, handing out flyers, organising workshops, visiting politicians, contacting polluting companies, developing policy frameworks. These tactics can successfully generate change. Almost half of the campaigns focussed on climate change achieved their goals, without the use of civil disobedience.

As social change researchers we look to understand the potential of tactics to generate change. But when we research activism, it is important to look beyond the headlines. Civil disobedience is not where ‘tactics begin’. As a movement works to raise awareness, create sympathy, motivate intentions to act, and ensure implementation, civil disobedience may instead be the end of the beginning. - By Robin Gulliver “Tell the truth and act as if the truth is real” – so goes the slogan of Extinction Rebellion (XR), a new international movement started in London in October 2018. The statement points to a discrepancy between the dire state of our environment and the lack of a real sense of emergency. While the majority of Australians’ understanding of the urgent need for action against climate change is reflected in their various every-day behaviours, there is still a lack of engagement in collective action for the environment. Despite the rise in individuals’ environmentally friendly behaviours, emissions continue to rise year after year. With 82% of all government subsidy still concentrated in ‘Clean Coal’, it’s clear that public policy still doesn't go far enough. While it might be more appealing to focus on improving our every-day behaviour as individuals, some argue that the pervasive messaging to get us to live our ‘best green life’ is actually a distraction designed to keep us content and away from collective action. However, there is a recent collective awakening about the need for systemic change over just changes in individual behaviour. These desperate times see the rise of more desperate measures of collective action such as non-violent civil resistance. Its practices and successes can be traced back to the Suffragettes, the American Civil Rights Movement, and LGBTQ movements. The specifics and strategies of civil resistance movements vary depending on their purpose and contextual factors. In this post, we’ll focus on civil resistance in the context of climate change action. The key principles remain similar across the movements:

Relevant audiences. Disruption is more effective in capital cities, as these are typically where national and international media are based. Just as labor strikes are effective against companies, closing down capital cities may be effective against governments. The inconvenience and disruption to the local populace and businesses is unavoidable. This can be harmful to the movement, so it’s important to inform the public about the urgency of the situation and the rationale behind the disruption. Prolonged disruption should be prewarned so emergency services can be rerouted.

Given the disruptive nature of civil resistance, public opinions can be quite divided. But if the sizes of the recent School Climate Strikes are anything to go by, the public’s appetite for drastic changes is growing rapidly, and this may come with corresponding greater support, or at least acceptance, of civil disobedience for climate change action. Environmental movements have to work to ensure that the political capital from mass mobilization for action isn’t wasted, as policy makers attempt to turn the conversation away from addressing climate change towards the law-breaking. Allies, policy makers, and the public have to be continually reminded that the story is about the science, the urgency of change, and the mass support for that change. Meanwhile, it’s up to the civil disobedience movements to galvanize support by informing the public about the movement’s rationale and considerations, and being inclusive of allies with varying political persuasions and beliefs. Regardless of whether you support civil disobedience or prefer more moderate activism, if there is a time to want more from our political system, the time is now. - Hannibal Thai Economic growth and environmental degradation: is it possible to have one without the other?

Numerous writers, such as Naomi Klein, have explored the relationship between environmental degradation and capitalism. They often conclude that any economic system requiring continual growth is simply incompatible with living within our environmental limits. The price our environment is paying in our quest for perpetual economic growth is clear. Indiscriminate forest clearing for agriculture production. The pollution of our shared climate for private gain. Bulldozing of wetlands for urban expansion. These all show how demands of continual economic growth steadily deplete and degrade the ecosystem services on which we depend. So should we expect the environmental movement to advocate for a new system of ‘sustainable’ economics? To answer this question, I studied 510 Australian environmental organisations in early 2017. I looked at a number of features of these groups, including whether they run campaigns on economic issues, or whether they incorporate economic issues in their advocacy. Groups ranged from large transnational foundations to small volunteer action groups, all working on a diverse range of environmental issues. Results show that few environmental organisations advocate for any significant change in our current economic values. For example, many organisations undertake grassroots campaigning to influence local policy decisions, such as by campaigning against specific local urban, coastal or resource extraction development. Yet very few organisations advocate for a steady state economy, or implement sustainable economic models such as establishing a not-for-profit social enterprise to support their advocacy activities. Why might this be so? My work research is uncovering a range of possible reasons:

Despite these barriers, a new way forward has been developing over the last few years. The dramatic growth of renewable energy cooperatives, community owned enterprises and campaigns such as the international divestment movement offer a beacon of hope. Such examples of success all share two key features: (1) They incorporate equitable and environmentally sustainable economic solutions into their campaigns, and (2) They network and share skills and resources across organisations. Another cause for hope is in the development of networks such as the New Economy Network Australia. Bringing together research findings from Institutes and Centres with on-the-ground case studies run by small volunteer local groups, these networks will allow the smashing of barriers to create effective economic and environmental change across local, regional, and national boundaries. The evolution of our first use of currency over 40,000 years ago into the complex and fascinating intricacies of our modern economic system is one of humanity’s crowning achievements. However, this evolution has come at a steep price to our environment. If you are someone who wants to change our economic values, use this information to join a group or build your own effective campaigns for change. Better yet, join a network and share your findings: be part of the community of change working for a socially, environmentally, and economically just future. - Robyn Gulliver

Climate change is real, so why the controversy and debate? Often the way science and ideas are communicated affects the response they motivate.

In this interview, I argue climate science communication should be informed by the psychology of persuasion and communication in conflict. I talk through concrete examples of effective and ineffective messaging and the key factors to consider. The ideas I present here are relevant for anyone working in science communication or social change. Key points include:

Watch the full interview below:

I'd love to hear your feedback. Please leave a comment or a question below and I'll get back to you.

- Winnifred Louis What makes a movement? Is it hanging a banner on a coal stack? Flying a drone over a whaling ship? Chants and marches? Or minutes, agendas, and long, repetitive planning meetings? Who makes a movement? Are they the paid staff with funds and strategic plans? Your neighbour giving an hour a week in their after work time? The local team planting trees in their reserve on a Saturday afternoon? Or people sitting and sharing links and posts on social media? Defining the environmental movement: who’s who, and what they do

Research about these questions has tended to focus on the operations of groups that shout the loudest. These groups are frequently those that are skilled at attracting media attention as part of their tactics, are the easiest to study, and have the systems in place to support external research. As a result Greenpeace, Friends of the Earth, WWF and other large multinational groups feature predominantly in the environmental movement literature. But is that image of a Greenpeace banner down a coal stack, or a 350.org rally with shouting, placard holding people really representative of what environmentalism in the field actually is? What about what everybody else is doing? There is a lot more to the environmental movement than its biggest, most vocal players. A closer look at what’s going on in the environmental movement in Australia quickly uncovers the overwhelming diversity of issues, approaches and actors that together create this movement. Over 500 groups with websites across Australia are active in some form of environmental advocacy—spanning diverse issues including pesticide use, population growth, climate change, catchment management, feral dog management and species conservation. If we add in those only using social media and word of mouth to promote their cause, then in fact thousands of groups, made up of tens of thousands of members and supporters are active in some way in creating this movement. What of campaigning, that classic approach to building a movement? Over 700 active campaigns are being promoted via Australian based websites. These range from local issues against coal mines to complex national campaigns focusing on marine protection, clean energy and land clearing. They involve tree planting, placard waving, wildlife rescue and letter writing. It’s pretty clear that there’s a lot going on. The vast majority of environmental groups in Australia have no paid staff, do not receive any substantial media attention, and do not use protest techniques or direct action to promote their cause. While they may not ‘win’ all, or even many, of their causes, clearly there is something special about the environmental movement that has united such a diversity of voices in such a short span of time. I’d like to get a sense of the collective action tactics and strategies used by these campaigning groups and the failures and successes that they are experiencing in the course of their activities. My PhD research aims to look under the surface of the latest protest banner and begin to understand why, what and who actually makes the environmental movement the global phenomenon that it has become today. - Robyn Gulliver When was the last time you changed your mind about something? What brought an important issue to your attention? Chances are it was something you saw, rather than something you read. The right image can be a powerful way capture and engage people with an important issue. For many of us, the haunting and graphic images of toddler Alan Kurdi washed up on a Turkish shore focused our attention on the Syrian refugee crisis. Yet not all images are created equal. Some are better than others. Some may even hurt your cause. For example, although they grab our attention, familiar and iconic images used in communications about climate change (i.e., smokestacks, polar bears) fail to make us feel like we can do anything about climate change. So which images are best? What properties of images increase the likelihood that the reader will engage with your overall message? My research on images used in communications about sustainable urban stormwater management found that images are more likely to engage when they: 1. Evoke an emotional connection Images are highly emotive and emotions help shape attitudes. Given that images are the first thing people see on a webpage or news article, they can create a connection with your message before a single word has even been read. Critically, different emotions can give rise to different motivations. For example, to approach or to avoid. For this reason it is important to select images that evoke emotions what psychologists call an ‘approach motivation’. That is, emotions that encourage the reader to pay attention to your message. Positive emotions, like happiness and pride, are known to have an approach motivation. Some negative emotions, like sadness and anger, can also motivate people to engage with your message. However, you should try to avoid images that elicit emotions with strong avoidance motivations, like disgust and fear. Such emotions may encourage the reader to simply switch off and not pay attention to your message. 2. Relevant to the topic When presenters use images in presentations that are congruent with what they saying, people are more likely to remember the message. This is because images that are not immediately understood as relevant to the topic reduce the ease with which the viewer can process your message. That is, irrelevant images increase the mental effort needed to process the overall message and can become a distraction. To avoid using irrelevant images, don’t make assumptions about what your target audience does and doesn’t understand about the issue you are communicating. For example, a cleaner ocean is a major goal of improved urban stormwater management initiatives, so images of ocean environments are often used in communications new stormwater initiatives. Unfortunately, our recent image study found that most people did not think that pictures of oceanic environments were relevant to the topic of stormwater management. 3. Personally relevant If the viewer sees something in an image that is personally relevant to them, they are more likely to engage with the message content. To increase the personal relevance of your message, choose images of locations that are highly familiar to your viewer (the more local, the better) or choose photographs of people that your target audience are more likely to identify with. For example, using images of melting ice caps to communicate about climate change suggests that the impacts are happening somewhere else to someone else. Conversely, images of extreme weather events (for example, in Australia, flooding is a major concern), highlight a more localised, and personally relevant, impact of climate change. - Tracy Schultz |

AuthorsAll researchers in the Social Change Lab contribute to the "Do Good" blog. Click the author's name at the bottom of any post to learn more about their research or get in touch. Categories

All

Archive

July 2024

|

Social Change Lab

Join our mailing list!Click the button below to join our mailing list:

Social Change Lab supports crowdfunding of the research and support for the team! To donate to the lab, please click the button below! (Tax deductible receipts are provided via UQ’s secure donation website.) If you’d like to fund a specific project or student internship, you can also reach out directly!

|

LocationSocial Change Lab

School of Psychology McElwain Building The University of Queensland St Lucia, QLD 4072 Australia |

Check out our Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2017

RSS Feed

RSS Feed