|

“Women are inferior to men.” “Men and women are constantly battling for power.” “Women are trying to take men’s power away.” Although sexist beliefs such as these are probably less prevalent today than in the past, they are still surprisingly prevalent, even in egalitarian societies. Researchers have fittingly dubbed such beliefs “hostile sexism”—which involves beliefs that women seek to take power away from men. A great deal of research now shows that hostile sexism is different than “benevolent sexism”—which involves the belief that women are wonderful but fragile and should be put on a pedestal by men. Although both forms of sexism can lead to discrimination against women, research shows that hostile sexism is more likely to influence overt aggression toward women in power, such as hostile derogation of female leaders, politicians, and feminists. But hostile sexism is not directed only toward female leaders, female politicians, or feminists. The everyday damage of hostile sexism may be even more pervasive in romantic heterosexual relationships. After all, we interact with our romantic partners more than anyone else. Indeed, the more men agree with hostile sexist beliefs, the more they exhibit verbal and physical aggression toward their wives and girlfriends. Why do attitudes about men’s and women’s power affect intimate relationships? Think about your own present (or past) intimate relationship. You probably depend on your partner more than anyone else for support, closeness, and intimacy, which makes romantic relationships rewarding and fulfilling. But this high level of dependence on your partner also challenges the power and control you have in your life. What your partner does affects you, and you them, and this dependence inevitably means your (and your partner’s) power is limited. Men who hold hostile sexist attitudes find this challenge to their power in romantic relationships particularly threatening. In recent research, my colleagues I and tested whether these concerns about losing power would mean that men who hold hostile sexist beliefs think they lack power in their relationships. Across four studies, involving almost 300 couples, and more than 500 individuals from the United States and New Zealand, we found that men who score high in hostile sexism think they have less power than less sexist men think they do in their romantic relationships. Moreover, these perceptions were biased in the sense that men who held greater hostile sexist beliefs underestimated the power they had over their partners compared to how much power their partners reported the men actually had. So if Jack is high in hostile sexism, he is likely to believe that Jill has more power over him than Jill reports she has. Our results suggest that men who more strongly endorse hostile sexism are more sensitive and vigilant about threats to power. This general sensitivity seems to lead men to underestimate the power they have in their own intimate relationships with women. This is important because when people think they lack power, they often behave in aggressive ways to try to restore their sense of power and control. Accordingly, across our studies, men scoring higher in hostile sexism perceived they lacked power in their relationships, which in turn predicted aggression toward their partners. This showed up on several measures of aggression—including derogatory comments, threats, and yelling at a partner during a conflict and both partners’ ratings of aggressive behaviors, such as being hurtful and critical, in their daily lives. It even applied when people recalled how aggressive they acted towards their partner over the last year. Furthermore, perceiving a lack of power—and not simply desiring to be dominant over women—explained the link between hostile sexism and relationship aggression. This is important because people often assume that sexist men feel powerful and are aggressive to maintain dominance. However, in intimate relationships, neither partner can hold all the power. Power is always shared, and both partners depend on each other. Men who are worried about losing power—that is, those who endorse hostile sexism—should find it particularly hard to navigate the power constraints in intimate relationships. Social scientists and the public often think about how sexism affects women in politics or the workplace. But hostile attitudes towards women are most routinely expressed in everyday interactions in close relationships. This research shows that sexist attitudes impact our intimate relationships, influence how we perceive our intimate relationships, and affect how we treat our partners. The aggression associated with men’s hostile sexism is obviously harmful to women, and combatting this aggression to protect women’s health and well-being is important. But this pattern of perception and behavior is also damaging for men. Being involved in relationships in which men think they lack power and behave aggressively in a bid to gain power will inevitably undermine men’s well-being as well. To cite just one example, research in health psychology suggests that experiencing chronic hostility or anger is bad for people’s cardiac health. The damage that aggression causes to intimate relationships might also reinforce hostile sexism by creating a self-fulfilling prophecy. Men who endorse hostile sexism are concerned about losing power, which promotes aggression, which then undermines women’s relationship satisfaction and commitment. The more women are dissatisfied, the more likely they are to withdraw from the relationship, express negative feelings, become less committed, and so on. These effects will not only threaten men’s power further but may also reinforce hostile attitudes that depict women as untrustworthy. This potentially damaging cycle highlights another reason why examining the impact of sexist attitudes within relationships is so important. - By Emily Cross Emily J. Cross is a postdoctoral fellow at York University in Toronto, Canada, where she studies how sexism functions in romantic heterosexual relationships. The current research was conducted with colleagues at the University of Auckland, New Zealand. This post is previously published on the Society of Personality and Social Psychology; Character and Context Blog For Further Reading Cross, E. J., Overall, N. C., Low, R. S. T., & McNulty, J. K. (2019). An interdependence account of sexism and power: Men’s hostile sexism, biased perceptions of low power, and relationship aggression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 117(2), 338-363. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000167 Davidson, K. W., & Mostofsky, E. (2010). Anger expression and risk of coronary heart disease: Evidence from the Nova Scotia Health Survey. American heart journal, 159(2), 199–206. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2009.11.007

0 Comments

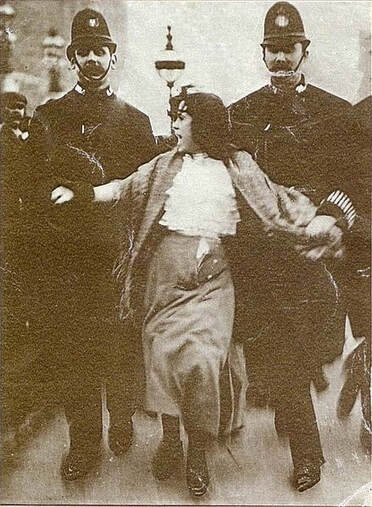

Who Runs The World? …Girls?: Why Female Leaders Struggle to Mobilise Individuals Toward Equality1/7/2019 Have you ever noticed that women are typically the ones spearheading gender equality movements? Think of the suffragettes, the #MeToo, and #TimesUp movements, the March for Women; All fronted by women – but at what cost? Research increasingly shows that relying solely on female leaders is not enough to achieve equality. Perhaps in response to this, there’s been a recent upsurge in male-led initiatives, such as the HeForShe movement, and the Male Champions of Change initiative. Both of these call on men to use their privilege and power to place gender equality on the agenda. These types of initiatives aren’t just companies taking a stab at something new – they’re backed by social psychological research. For example, two recent studies looking at how leader gender affected individuals’ responses to calls for equality found that men and women were more likely to follow a male leader into action (Hardacre & Subasic, 2018; Subasic et al., 2018). Importantly, the only change between the study conditions was the leader’s name and pronouns (e.g., from “Margaret” to “Matthew”). Below, we talk about some of the reasons why female leaders struggle to mobilise people toward equality. “Think manager, think male”: Leadership prototype embodies masculine attributes In our heads, we hold a 'prototype' of particular categories and roles – a fuzzy set of characteristics, attitudes, and behaviours that define certain groups and occupations. For example, if you were to think of a leader, you might think confident, assertive, and even male. Turns out this “think manager, think male” mindset is pervasive. Numerous leadership theories emphasise the desirability of stereotypically masculine traits in leaders. In fact, female leaders are frequently seen as ineffective because individuals’ ideas of effective leadership overlap with agentic male stereotypes (assertive, dominant), rather than communal female stereotypes (warm, nurturing). Even when female leaders do adopt masculine behaviours (such as those seen as typical of leaders), they face backlash because they’re seen as “violating” their traditional caring stereotype. This signifies a Catch-22 situation whereby female leaders are “damned if they do and doomed if they don’t!” Female leaders face accusations of self-interest, while male leaders are seen as having something to lose. It’s also difficult for female leaders of gender equality movements not to appear self-interested and overly invested in their cause (with good reason, given that it IS in their group’s best interests to challenge the status quo!). Essentially, women’s efforts at reducing inequality can be seen as furthering the interests of themselves and their group, and the more women are viewed as trying to benefit their own group, the more cynicism and dismissal they encounter. This can undermine women’s efforts at social change because acts of self-interest are less convincing and influential than acts that seem to oppose one’s best interests. In contrast, because many view gender equality as a zero-sum game, when men challenge gender inequality they’re seen as having something to lose – namely the rights and privilege that accompany their membership of a high-status group. This ultimately affords men greater legitimacy and influence, and therefore greater ability to mobilise followers. Male leaders possess a shared identity with men and women, while female leaders only share an identity with women. Possessing a shared identity with those you are trying to mobilise is at the crux of effective leadership, because those considered “us” are considered more influential than “them”. Herein lies another problem for female leaders. In gender equality contexts, male and female leaders both share a cause with women engaged in gender equality movements whilst men benefit from an additional shared social identity with men.. Meanwhile, no such shared identity yet exists for female leaders looking to mobilise a male audience. Instead, they’re seen as outgroup members by men in terms of their gender group membership, but also in terms of shared cause because gender equality is often seen as a women’s issue and of no benefit to men. Conclusion Paradoxically, by virtue of their gender and the privileges it permits, male leaders seem to have the ability to undertake gender equality leadership roles and mobilise men and women more effectively than female leaders. Research suggests that, among other reasons, this is due to leadership prototypes typically comprising masculine attributes, female leaders’ inability to escape accusations of self-interest, and male leaders’ possession of a shared identity with both male and female followers. It will be interesting to see how long the male ally advantage persists: in the longer term, effective feminist leadership will presumably eliminate the ironic inequality. - Guest post by Stephanie Hardacre (University of Newcastle). As for many other nations, gender equality in Australia has increased significantly over the last century. By 1923, all women in Australia had the right to vote and stand for parliament. In 1966, women earned the right to continue employment in the public sector after marriage through the removal of the marriage bar (a ruling that barred women from working in many careers after marriage). Female workers in Australia were granted the right to equal pay in 1969, and the 1996 Workplace Relations Act required men and women to receive equal pay for equal work. Whilst inequalities do persist, (e.g., the average Australian woman is earning 85c for every dollar earned by men) there is considerable support for gender equality in the public sphere. However, there is less support for gender equality in private life. An Australian attitudes survey found that 16% of Australians believe men should take control in relationships and be the head of the household, 25% of Australians believe that women prefer men to be in charge of the relationship, and 34% believe it’s natural for a man to want to appear to be in control of his partner in front of his male friends. This issue of gender inequality in the public versus the private sphere has come to the forefront of public discussion recently. The debate around the equal distribution of household chores and caregiving responsibilities is occurring both here and abroad. Heterosexual Australian women average seven hours more housework per week than their male partners. This inequality often starts in childhood, with female children often expected to take on more chores than their male siblings. In adult relationships, habits started in the early stages of the relationship can further increase unequal responsibilities. In this stage, women are more likely to be at home looking after children and cleaning up the house. This dynamic continues even after the female partner returns to work. Early exposure to unequal gender roles and failure to establish equitable dynamics in the early stages of the relationship, can lead to unequal expectations of men and women in romantic relationships. There is light being shed on the double standard regarding expectations of men and women. For example, men are praised for completing chores and looking after their children, when women are simply expected to do these things. As one father noted, the disproportionate praise heaped on men for simply interacting with or looking after their children is not only unfair for women, but condescending to men. Not only do these disparities reinforce unequal gender roles, limiting both men and women, but they may play a role in domestic abuse. When the onus of responsibility for domestic tasks is put onto women, this expectation may be used to justify abusive responses to a failure to maintain standards. For example, if a house is untidy, or a child gets sick or injured, instead of simply acknowledging it as something that happens, it can be viewed as the female partner’s fault, and the female partner’s failure to fulfil their role. Obviously, this is not the case for most relationships, but inequality in the home may be seen by some as legitimising abuse. Unequal home dynamics may also alter the perceptions of work. For example, even if both partners in a heterosexual relationship engage in paid work, emphasis on the female partner’s domestic responsibilities reinforces the idea that the man should be the primary income earner. This also highlights that his career is more important than hers. If the woman’s income or career success exceeds her partner’s, this may result in her partner reinforcing greater inequality in the home in an attempt to retain a feeling of power and control. The recent public discussion of gender equitable distribution of domestic responsibilities raises the question: Why did it take so much longer for equality in the home to become a priority in a nation that prides itself on progressive attitudes regarding gender equality? Perhaps the persistence of gender inequality in the home reflects residual hidden sexism in a culture where the beliefs may not have held pace with changing public norms. - Kiara Minto Coercive control is when an abuser consistently or repeatedly uses a pattern of behaviours to insert themselves into, and control, the abused partner’s life. It is a pattern originally identified by Evan Stark in 2007, which aims to strip the victim of independence and self-confidence. Coercive control is associated with long-term harm and can pose significant risk from the abuser even after the relationship is over. Given the role that coercive control plays in understanding and responding to intimate partner violence, below are 4 things everyone should know about what it is and how it functions.

1. What does coercive control in romantic relationships look like? Coercive control involves abusers attempting to dictate every aspect of their partner’s lives, and does not necessarily require physical violence. Some examples of non-physical, abusive behaviours are:

2. The impact on health and well-being. The gradual loss of independence that comes with coercive control, and the consistent experience of stress and tension, can have a lasting negative impact on the health and well-being of victims. The road to recovery from non-physical elements of coercive control and the destruction of self-esteem, are often reported as a challenge as great as recovery from physical violence. For victims, a considerable struggle after leaving their abusive partner is regaining confidence and faith in themselves. 3. The risk of retaliation. Even after leaving a relationship with coercive control there is a risk of retaliation from the abuser. Risk of retaliation is associated with the amount of coercive control an abuser has over their victim, rather than the physical or non-physical nature of the previous abuse. The risks are clearly illustrated by the cases of Claire Hart in the UK, and Tara Costigan in Australia. Although neither Claire nor Tara experienced physical abuse from their partners during the course of their relationships, both were tragically murdered after taking steps to leave their controlling abusers. In less extreme but still very damaging cases, victims experience continued abuse from their former partners such as harassment or stalking. In cases with children in particular, abuse can continue through court proceedings. 4. Coercive control and the law. It can be particularly difficult to prosecute coercive control involving non-physical abuse in a legal system that presses criminal charges based on single instances of criminal behaviour. The UK recently implemented a coercive control offence in an attempt to remedy this problem. Unfortunately, the results of this law do not appear to be as positive as might have been expected. As we progress in our understanding of intimate partner violence it is important to develop a deeper understanding of coercive control. We need to further our awareness of the warning signs, the harms it causes, the risks it poses, and the complexities of this issue. It is clear from what we now know that a lack of physical violence doesn’t necessarily reduce the harm or risk of retaliation for those who have experienced abuse. We need to move away from a black and white understanding of abuse that discounts the severity of non-physical abuse to come to grips with the true nature and scale of the problem. - Kiara Minto |

AuthorsAll researchers in the Social Change Lab contribute to the "Do Good" blog. Click the author's name at the bottom of any post to learn more about their research or get in touch. Categories

All

Archive

July 2024

|

Social Change Lab

Join our mailing list!Click the button below to join our mailing list:

Social Change Lab supports crowdfunding of the research and support for the team! To donate to the lab, please click the button below! (Tax deductible receipts are provided via UQ’s secure donation website.) If you’d like to fund a specific project or student internship, you can also reach out directly!

|

LocationSocial Change Lab

School of Psychology McElwain Building The University of Queensland St Lucia, QLD 4072 Australia |

Check out our Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2017

RSS Feed

RSS Feed