|

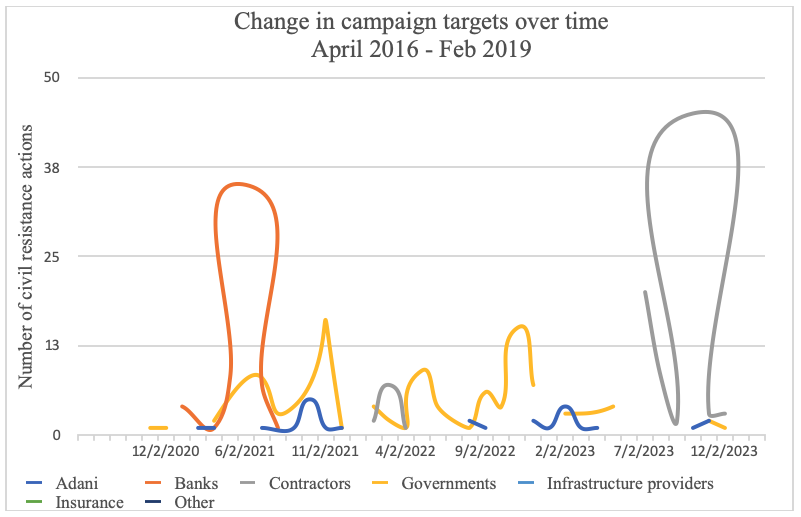

Extinction Rebellion and Fridays for Future burst onto the world stage in 2018 to demand urgent action on the climate crisis. These movements organized strikes, blockades and demonstrations, building on the work of activists before them. But how frequently do climate activists use civil resistance? How do they sustain their campaign and organizing despite various challenges and repressive responses by the opponents and their allies? And what has civil resistance against climate change been able to achieve? In a forthcoming ICNC Monograph, we use data collected on hundreds of Australian climate change groups and campaigns to examine these questions. This data demonstrates impressive levels of activity: 729 Australian groups organized 27,934 events from 2010 to 2019, of which 3,705 involved civil resistance tactics. Rallies were the most popular (1,872), but activists also organized occupations, die-ins, strikes and bicycle swarms, among others. We also analyzed the outcomes of 193 campaigns against climate change organized by these groups, which targeted businesses, governments, health and education providers and individuals. Eighty campaigns were linked to a successful outcome, such as overturning punitive fees for solar panel owners and securing a political commitment to close a coal fired power station. Our rich dataset has become a portal into the successes and shortcomings of nonviolent resistance for environmental change in Australia. One of those successes highlighted in our study is the Stop Adani campaign. This campaign merits its own storytelling so that other campaigns and activists elsewhere might benefit from and utilize some of its key learnings. Lessons from the Stop Adani campaign The Stop Adani campaign aims to halt the construction of a large thermal coal mine located in Central Queensland. Since its proposal in 2010, it has generated widespread public outrage despite ongoing political support for the development. More than 250 environmental groups have participated in the campaign since its inception, using tactics as diverse as film screenings, nationwide ‘Stop Adani’ human signs, disruption of the 200-year celebration of the bank proposing to fund the mine, and the development of a permanent blockade camp to facilitate civil resistance actions along the proposed mine, port and railway infrastructure corridors. Despite 11 years of activism, the mine is now under construction. Its progress however has been marred by delays, cost overruns and legal challenges as a result of the ongoing campaign. At the same time, the environmental activism sector in Australia has endured political crackdowns on the use of civil resistance tactics and attacks on the charitable status of environmental organizations. How has the campaign been able to persist and achieve successes despite these challenges? Our research identified three characteristics of the Stop Adani campaign which may help explain its power. ‘Directed network’ campaigns can sustain, support and diversify climate activism The Stop Adani campaign uses a directed network structure, where a central, professional hub supports volunteer-based grassroots groups across the country working on the campaign. The centralized team focuses on strategy, development of campaign information materials, and relationship building with corporate and political powerholders. This innovative structure has supported the emergence of over 120 local Stop Adani groups, while also enabling groups to specialize in different tactical approaches. Some groups, for example, have specialized in political lobbying, while other groups use civil resistance tactics to stop work developing the mine and its associated infrastructure. Diversified targeting can enable small, achievable wins even in the face of larger failure The Stop Adani campaign ultimately seeks to stop the construction of the new coal mine. However, the campaign has successfully targeted many other organizations that either support or enable the mine to conduct its work, such as banks, insurance companies, contractors, local authorities and the state and federal governments. This strategy has enabled the campaign to achieve inspiring successes even while the mine continues to be built. In our analysis we tracked the number of campaign events and their targets between 2016 and 2019. After the ‘Big 4’ Australian banks ruled out funding the mine in 2017, increased targeting against federal and state governments occurred in the election periods. By 2019, mine contractors, insurance companies and infrastructure providers were targeted with a range of tactics including protests, blockades and sit-ins. One after the other they have cancelled their associations with the mine. Today, no major Australian bank or private investor will back the project. Networking helps sustain grassroots civil resistance Our data suggest that many of the grassroots climate action groups which were formed independently have struggled to survive. Whereas campaigns using a directed network structure, such as Stop Adani, Extinction Rebellion and the Divestment campaign have been able to weather the financial, legal and psychological challenges of sustaining their actions while also pushing back against vested interests. Networking between groups using different advocacy and civil resistance strategies has enabled efficient use of skills and resources. For example, groups have worked together to develop and sustain the ‘Camp Binbee’ blockade site for over three years. With support from a number of large Australian environmental NGOs, some groups have won complex legal cases against the mine while others have provided detailed financial research to attack the financial structures that support fossil fuel demand. Networking has enabled environmental groups to combine their resources to increase their power to create change. The future of civil resistance against climate change More than 30 years after Australians first used civil resistance tactics to demand climate action, the crisis has continued to escalate. Yet changing political realities and sustained, resilient activism against entrenched fossil fuel interests offer hope for the future. Directed network campaigns such as Stop Adani have helped build power across the environmental activism network and mobilized larger numbers of volunteers to engage in civil resistance. Activists are supported by specialist training and resource development organizations such as The Commons Social Change Library and The Change Agency. Organizing continues both offline and online even in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic. Our monograph suggests that the vibrant, diverse climate civil resistance ecosystem in Australia is succeeding, and invites similar analyses from around the world to inform advocacy and mobilization to effectively protect our environment. Time will tell whether this is sufficient to avert the worst of what awaits ahead. - by Robyn Gulliver, Kelly Fielding and Winnifred R. Louis This post was previously published on the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict: Minds of the Movement blog. Dr Robyn Gulliver is a multi-award winning environmentalist, writer and researcher who has served as an organiser and leader of numerous local and national environmental organisations. Her research focuses on the antecedents and consequences of environmental and pro-democracy activism. Professor Kelly Fielding is an environmental psychologist at the University of Queensland whose research focuses on developing ways to promoting environmental attitudes and actions. She addresses a range of environmental issues including climate change communication and action. Professor Winnifred R. Louis (PhD McGill, 2001) is a Professor in Psychology at the University of Queensland. Her research interests focus on the influence of identity and norms on social decision-making.

0 Comments

|

AuthorsAll researchers in the Social Change Lab contribute to the "Do Good" blog. Click the author's name at the bottom of any post to learn more about their research or get in touch. Categories

All

Archive

July 2024

|

Social Change Lab

Join our mailing list!Click the button below to join our mailing list:

Social Change Lab supports crowdfunding of the research and support for the team! To donate to the lab, please click the button below! (Tax deductible receipts are provided via UQ’s secure donation website.) If you’d like to fund a specific project or student internship, you can also reach out directly!

|

LocationSocial Change Lab

School of Psychology McElwain Building The University of Queensland St Lucia, QLD 4072 Australia |

Check out our Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2017

RSS Feed

RSS Feed