|

Perhaps there is no worse way of welcoming the new decade of 2020 than the fear and loss caused by the rapid spread of COVID-19. Despite its relatively lower lethality rates (3.4% as of March 3, 2020) compared to previous similar pandemics, such as MERS (34%) and SARS (9.6%), as quickly and widely as the coronavirus has spread across the world, so too has the fear, anxiety, and worries about the virus. Lockdown procedure first took effect in Wuhan, the site where the infection was first identified, followed by Italy, and now countries around the world are enforcing varied levels of lockdown restrictions. After the lockdown in Italy and other places, photos and videos quickly circulated through social media, describing the miserable conditions of cities in lockdown. Some were left traumatised, while some others prepared in case a similar lockdown procedure was enforced by authorities in their country. Australia is no exception, experiencing the virus and the accompanying social media terror. It took only 64 days since the first case of COVID-19 was identified in Australia to record almost 4000 patients on 29th March 2020. Given the rapid escalation of the virus, people immediately began stockpiling items considered essential for survival including: canned foods, cooking oils, diapers, tissues and toilet paper. Tragedy of the Commons There is a classical notion called Tragedy of the Commons that perfectly describes the social dilemma experienced in our situation. William Lloyd was the first person to define this issue in 1833 to refer to a situation when shared resources that will be available should individuals use as according to their needs, become less available because people behave contrary to the common good of all users. Such a situation creates a vicious cycle: fear of scarcity encourages people to buy in a large quantity, and by monopolising or stockpiling certain resources, “panic buying” creates a scarcity of various goods that had previously existed only in the imagination of those panic buying. Even when individuals know that under optimal conditions the system can work to deliver the products, once a norm of stockpiling is established, it becomes a rational choice not to let oneself be the one left without critical resources. The collective buying not only affects the quantity of goods, but can also trigger aggressive behaviour as the resources become scarce. Why does scarcity stir up aggressiveness? Scarcity logically occurs when demand outweighs supply, which results in shortages, ignites competition for these resources, and increases their perceived value. Scarcity of the things that people consider essential is a perfect atmosphere for an instrumental aggressive behavior (behaviors intended to harm or injure another person as a means to obtain the resources) to occur. In performing aggressive action, individuals instinctively evaluate the cost and benefits of their action. In this case, hostile behavior is only performed if and when the fear caused by the absence of the resources outweighs the risk associated with fighting. One factor that is critical is whether there are social norms (rules or standards for behaviour) that regulate the aggression. Humans are more complex than basic survival instincts, and values and identities also contribute in determining individuals’ actions. In this sense, people whose values condemn violence and favor humanity, or whose groups have norms of sharing and cooperation, may never consider aggression as an option regardless of their perceived need for the resource in question. How to avoid the emergence of aggressive behaviour in a crisis?

In the case of stockpiling happening around us today, aggression is activated by competition for resources that are believed to be scarce. Competition often arises from worries of not being able to survive. These worries can influence us to think of others as a threat, thus providing another reason to behave aggressively. A second, more powerful reason is then created when social media and media magnify the images of aggressive behavior, creating a perceived norm of aggression that is at odds with the reality of every-day cooperation and politeness. In response to this, I believe trust is the answer, and regaining people’s trust is our main homework. Trusting that suppliers are implementing their best strategies to ensure sustainability and fair distribution of stocks is important, but most importantly, trusting that people around us are just like us, humans with full dignity and values. Highlighting our shared identities is often the bedrock of that trust: focusing on our common faith, nationality, or humanity invokes our common agenda to come together to support each other in difficult times. As soon as we show trust and respect the system by following the advice from the authorised parties, and following what the majority of people do instead of the minority, we could show the world who we actually are: a united human species whose survival is determined by shared dignities, values, and respect more than by violence. May 2020 be best remembered not by the chaos and fear caused by the COVID-19, but by the true values that defines us as humans, whose compassion, and not aggression, is what maintains our existence. - By Eunike Mutiara

0 Comments

Reflections on Cardinal Pell and Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse Allegations16/12/2019 In Australia, with the recent failed appeal of Cardinal Pell, the problem of child sex abuse in institutions has again been thrust into the media spotlight. Surprisingly, many continue to stand by Pell. Several prominent figures including former prime ministers Tony Abbott and John Howard publicly supported Pell. In addition, even after the failed appeal, many members of the Catholic Church have continued to argue for Pell’s innocence and the Catholic Church has refused to remove a plaque of Cardinal Pell from St Mary’s Church in Sydney despite protests. This begs the question of how can Pell’s supporters persist in believing in his innocence despite his conviction and failed appeal? My research into institutional responses to child sexual abuse may provide some insight into the question of why some continue to support Pell. We are all members of various groups and some of these groups are more important to us than others. Our group memberships can influence and bias how we respond to allegations of wrongdoing against other members of our groups. In the instance of Cardinal Pell who is one of the most powerful figures in the Catholic Church, membership in the Catholic Church may influence people’s judgements of the allegations against him and even his conviction. A theory called the “black sheep effect” suggests that when a person engages in wrongdoing, they will be judged most harshly by members of their own group in order to reject them and their behaviour and protect the reputation of the group. However, this effect is typically found in cases where the guilt is certain. In the case of Cardinal Pell, with some of the evidence withheld from the public, and as Pell maintains his innocence, the guilt cannot truly be considered certain. My research suggests that when there is any uncertainty in the guilt of the alleged offender, we are likely to see the opposite of the “the black sheep effect”. Specifically, Catholics are more likely to be protective of the accused and sceptical of the accuser. This is in line with efforts of the Catholic league to invalidate the allegations against Pell by maligning the character of the accusers. According to my research findings, the desire to protect Pell and the scepticism of his accusers would be particularly strong amongst those who identify strongly as Catholic, regardless of the quality of the evidence available. As a public figure, and staunch Catholic Tony Abbott may be particularly motivated to maintain Pell’s innocence and disbelieve allegations of child sex abuse as accepting Pell’s guilt would reflect negatively on himself and his religion. Similarly, although John Howard is not a Catholic, he is a Christian and has been personally acquainted with Cardinal Pell for several decades. Whilst it is likely that many supporters of Pell are unwilling to consider the possibility of his guilt due to subconscious biases motivating their judgements, it is also important to note that when speaking to leaders of the Catholic church, Justice Peter McClellan (head of Australia’s royal commission into child sex abuse) found that some argued that child sex abuse was a moral failure rather than a criminal act. Consequently, accepted allegations were often met with an inadequate response and the offender remained in the ministry. Recommendations for the future Given what we now know about child sex abuse in institutions, it’s clear that there has been a systematic failure for decades. My research suggests that allegations would be best dealt with by those not invested in the group of the accused. This is backed up by the recommendations of the royal commission; that those intending to enter the ministry should be subject to external psychological testing and should be removed from the ministry permanently if an allegation of sexual abuse is substantiated. Essentially, organisations should not be solely responsible for policing themselves. If you have experienced abuse within the Church or elsewhere, please contact Lifeline on 13 11 14 or one of the other help services recommended by the Royal commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse. - By Kiara Minto "I am vegetarian" - this statement doesn’t just communicate personal eating habits, but also one’s membership in a group of people who distinguish themselves from the meat-eating society through personal values and attitudes. As the proverb “You are what you eat” goes, there are correlations between one’s diet, be it vegan or vegetarian, and one’s personality and values. Recently, there has been a rise in research into the "veggie personality". Veggie is used informally in some countries, such as the UK or Germany to refer to vegetarians. In this context, the term encompasses both vegetarians and vegans. This article will give a short overview of the current state of research on the so-called “veggie personality”. Research in the West shows that veggies tend to be educated, young, and female. But why are older people, less educated individuals, and males, significantly less willing to reduce their meat consumption and more likely to hold negative attitudes towards veggies. Veggies buck tradition Being a veggie means rejecting the consumption of meat or all animal products but in the West these foods often form part of a country’s traditions. Those who hold more tightly to traditions and are less open to new experiences will be more opposed to a veggie diet. This is supported by various studies showing that veggies differ from their meat-eating counterparts (omnivores) in important attitudes and personal characteristics. For example, veggies tend to be more politically liberal and less attached to traditions than omnivores. This may also explain the positive connection between a veggie diet and higher education as compared to less highly educated people, more highly educated people tend to be more politically liberal. Try new things… become a Veggie Additionally, veggies are more open to new experiences than omnivores. Meaning, they are more curious and unconventional, more likely to challenge existing social structures, and more likely to try new things, like new diets. Therefore, findings that show openness tends to decrease with age may explain why older people are less likely to opt for a veggie diet. The Veggie worldview and masculinity Veggies also tend to have more universal world view than meat-eaters. They support values such as peace, social justice, and equality - which they also extend to animals. For example, veggies generally ascribe more complex emotions to animals than do omnivores. They are more concerned about animal welfare, donate more to animal benefit organizations, and make greater efforts to preserve and protect the environment. The consumption of meat contrasts with the above-mentioned values as it signifies human’s dominion over animals. Even in modern, largely gender-equal societies, men are more likely to value dominance and power than women are. Veggie men are perceived as less masculine compared to omnivorous men because masculinity is associated with meat. That makes it harder to reduce meat consumption for men than for women. More broadly, social and cultural norms contribute to the gender, generation, and political group differences mentioned above, as different groups have different learned rules or standards for their behaviour, including eating. In summary, the "veggie personality" encompasses a range of personality traits, political, and moral attitudes including being politically liberal, having high openness, valuing social justice and equality. These moral concerns are also extended to animals which make the consumption of meat and animal products incompatible with the “veggie personality”. Many aspects of the veggie personality run counter to traditional normative framing of masculinity. Thus women are overwhelmingly more likely to reduce their meat consumption compared to men. As society moves away from archaic notions of gender roles and embraces more universal values, hopefully we will achieve the much-needed reduction in global meat consumption.

Lean in! Take a seat at the table! Show the will to lead! Women are often told that this is the way to get ahead in the workplace and overcome inequality. So, what opportunities are available for women in academia to lean in? We know that, within academia, women are more likely to be asked, and to take on, so-called service roles. These roles might indeed lead to a seat at the table, but research shows that these roles are often under-valued when it comes to career progression. But if you’re asked to take on a leadership role – or if, like me, you actually like academic leadership – how can you ensure that ‘leaning in’ enhances your career? Here are six ‘top tips’ gleaned from my experiences: 1. Be selective In academia, women are more likely to be asked to take on more ‘nurturing’ roles. This often reflects commonly held stereotypes about what both women and men are ‘good at’. But I’ve found that academic leadership works best if you’re genuinely passionate about your role. When I took on the role of Director of Education in 2012, I truly believed that we could do things better in the department and wanted to focus my energies to improve the student experience. For other people (and I’m going to name drop some of my amazing colleagues here) their passion might be promoting increased access to higher education (Lisa Leaver – also speaking in Soapbox Science Exeter 2019) or promoting women in science (Safi Darden – one of the amazing Soapbox Science organisers). 2. Negotiate If you’re asked to take on a leadership role, don’t be afraid to negotiate (especially if it’s clear that none of your colleagues want the role!). Many women don’t negotiate because they recognise, consciously or subconsciously, that negotiating is fraught for women in ways that it is not for men. Indeed, research suggests that women are equally likely to negotiate than men (e.g., asking for a raise), but are much less likely to be successful. Sadly, you are unlikely to get a pay raise for taking on an academic leadership role, but you might be able to negotiate for other benefits, such as a period of study leave at the end of your tenure or additional research support or access to training opportunities (e.g., the Aurora program). 3. Delegate Full disclosure here: I am very bad at delegating…but this was one of the key lessons I took from my first leadership role as Director of Education into my second role as Director of Research. There are many reasons why it’s important to delegate: if you don’t, and you try to do everything yourself, you will burn out! But delegation is also about communicating trust and confidence in the people around you – that you believe that they will do a good job (even if it’s not exactly the way you would do it!). Delegation is about empowering others. So, if people offer help – take it! 4. Say no Full disclosure again: I find it very hard to say no…but we (women) need to do it more often. Throughout my career, I’ve often been rewarded for saying ‘yes’ – sometimes this has led to new collaborations or opportunities and people like you more if you do. But as you progress in your career, saying no to some things allows you to say yes to other things. In the last year, I’ve had a ‘no support group’ with some of my friends – each week we share the tasks we’ve said no to, and we congratulate each other on how we’ve protected our time or saved ourselves from a future obligation. 5. But it is OK to say yes As I’ve said, I find it hard to say no, and often end up saying yes. I confessed this to my ‘support group’ and my very wise friend noted four considerations when deciding whether to say yes. First, could the person do it themselves, even if it’s inconvenient or difficult? Second, can you do it without neglecting your own responsibilities, relationships, or self-care? Third, are you happy to do it or will you resent it later? Finally, will it help them to be independent or will it make them more dependent in the future? By thinking about these questions, you might find yourself saying yes to optional tasks, but you will be more mindful about it. 6. Do it well To return to the idea of ‘leaning in’, it’s not enough to take your seat and keep it warm. For academic leadership to enhance your career, you need to get stuff done and make a difference. When you take on a role, take time to think about how you can make your workplace a better place (however you define better) and how you can achieve it. Make sure that your achievements are visible (to help your career) and ensure that you’ve put structures in place that will make any impact sustainable after you leave the role (see #3). Being an academic leader is one of the most exciting and rewarding parts of my job – every day I feel like I’m making an important contribution to my discipline and I get to support my colleagues, especially early career researchers, to achieve their goals. - Guest post by Joanne Smith (Twitter: @jorosmith)

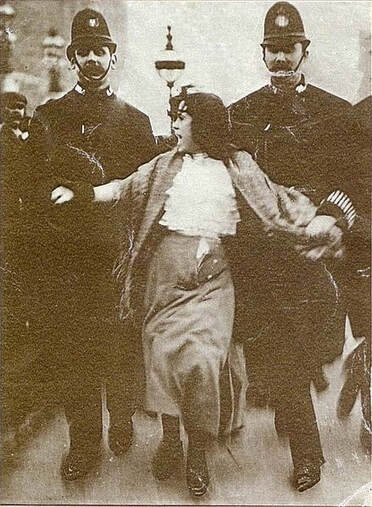

Joanne Smith is an Associate Professor and Director of Research in the School of Psychology at the University of Exeter. She was also Director of Education from 2012-2014. Joanne studies how the groups that we belong to influence our behaviour and how we can harness insights from social psychology to promote behaviour change. She studies social influence and behaviour change across multiple domains, with a focus on health and sustainable behaviour. Joanne will take part in our Soapbox Science Exeter event, on Saturday 29th July 2019. There she will talk about “With friends like these: How groups influence our behaviour for better…or for worse”. This blog post is previously published on Soapbox Science Who Runs The World? …Girls?: Why Female Leaders Struggle to Mobilise Individuals Toward Equality1/7/2019 Have you ever noticed that women are typically the ones spearheading gender equality movements? Think of the suffragettes, the #MeToo, and #TimesUp movements, the March for Women; All fronted by women – but at what cost? Research increasingly shows that relying solely on female leaders is not enough to achieve equality. Perhaps in response to this, there’s been a recent upsurge in male-led initiatives, such as the HeForShe movement, and the Male Champions of Change initiative. Both of these call on men to use their privilege and power to place gender equality on the agenda. These types of initiatives aren’t just companies taking a stab at something new – they’re backed by social psychological research. For example, two recent studies looking at how leader gender affected individuals’ responses to calls for equality found that men and women were more likely to follow a male leader into action (Hardacre & Subasic, 2018; Subasic et al., 2018). Importantly, the only change between the study conditions was the leader’s name and pronouns (e.g., from “Margaret” to “Matthew”). Below, we talk about some of the reasons why female leaders struggle to mobilise people toward equality. “Think manager, think male”: Leadership prototype embodies masculine attributes In our heads, we hold a 'prototype' of particular categories and roles – a fuzzy set of characteristics, attitudes, and behaviours that define certain groups and occupations. For example, if you were to think of a leader, you might think confident, assertive, and even male. Turns out this “think manager, think male” mindset is pervasive. Numerous leadership theories emphasise the desirability of stereotypically masculine traits in leaders. In fact, female leaders are frequently seen as ineffective because individuals’ ideas of effective leadership overlap with agentic male stereotypes (assertive, dominant), rather than communal female stereotypes (warm, nurturing). Even when female leaders do adopt masculine behaviours (such as those seen as typical of leaders), they face backlash because they’re seen as “violating” their traditional caring stereotype. This signifies a Catch-22 situation whereby female leaders are “damned if they do and doomed if they don’t!” Female leaders face accusations of self-interest, while male leaders are seen as having something to lose. It’s also difficult for female leaders of gender equality movements not to appear self-interested and overly invested in their cause (with good reason, given that it IS in their group’s best interests to challenge the status quo!). Essentially, women’s efforts at reducing inequality can be seen as furthering the interests of themselves and their group, and the more women are viewed as trying to benefit their own group, the more cynicism and dismissal they encounter. This can undermine women’s efforts at social change because acts of self-interest are less convincing and influential than acts that seem to oppose one’s best interests. In contrast, because many view gender equality as a zero-sum game, when men challenge gender inequality they’re seen as having something to lose – namely the rights and privilege that accompany their membership of a high-status group. This ultimately affords men greater legitimacy and influence, and therefore greater ability to mobilise followers. Male leaders possess a shared identity with men and women, while female leaders only share an identity with women. Possessing a shared identity with those you are trying to mobilise is at the crux of effective leadership, because those considered “us” are considered more influential than “them”. Herein lies another problem for female leaders. In gender equality contexts, male and female leaders both share a cause with women engaged in gender equality movements whilst men benefit from an additional shared social identity with men.. Meanwhile, no such shared identity yet exists for female leaders looking to mobilise a male audience. Instead, they’re seen as outgroup members by men in terms of their gender group membership, but also in terms of shared cause because gender equality is often seen as a women’s issue and of no benefit to men. Conclusion Paradoxically, by virtue of their gender and the privileges it permits, male leaders seem to have the ability to undertake gender equality leadership roles and mobilise men and women more effectively than female leaders. Research suggests that, among other reasons, this is due to leadership prototypes typically comprising masculine attributes, female leaders’ inability to escape accusations of self-interest, and male leaders’ possession of a shared identity with both male and female followers. It will be interesting to see how long the male ally advantage persists: in the longer term, effective feminist leadership will presumably eliminate the ironic inequality. - Guest post by Stephanie Hardacre (University of Newcastle). People often categorise themselves as either politically conservative or liberal. From a social psychological perspective, we often categorise ourselves and compare ourselves with other people. We like to identify who we are, and we do this by distinguishing ourselves from people who belong to other groups. Conservatism and liberalism are opposite ends of the political spectrum; in our perception nowadays, they are worlds apart. However, conservatism and liberalism are relative, and sometimes even cultural. For example, people in new generations often refer to themselves as less conservative and more liberal than older generations. Westerners may refer to themselves as less conservative and more liberal than Easterners. Being conservative in the American context might be considered liberal in the Chinese context. What does it actually mean to be more or less conservative (or liberal)? Is this a difference in cognitive processing? Or a social difference that we have picked up from the society around us? Protecting vs. Providing Motivation Liberals and conservatives differ in what motivates them. Studies with Western samples show that political lefties (liberals or progressives) tend to support policies that provide welfare for societies, whereas political conservatives tend to support policies that aim to protect their country from external harm. Such differences are rooted in the psychological distinction between approach and avoidance motivations. Approach motivation focuses on how we can gain benefits. In general, this motivation seeks to provide well-being by doing good things for ourselves and for others (prosocial behaviours). People with approach motivation are likely to support individual autonomy and social justice. In contrast, avoidance motivation focuses on avoiding harms, and what we should not do. Generally, this motivation seeks to prevent harm and to stop bad behaviours. People with avoidance motivation are likely to be responsive to threat and support social regulations. However, this does not mean that people have only one type of these motivations and not the other. We all have some degree of both motives, and all react to changing situations by adjusting our current motives, but may lean towards one side more overall. More vs. Less Negative Sensitivity Neurologists and psychologists have found a link between people’s political orientation and sensitivity to negative environments. This is known as the negativity bias. A negativity bias means that humans generally tend to pay more attention to negative things. For example, we are generally quicker at recognising angry faces than happy faces. Even though we all have a negativity bias, the degree of negativity bias may be different from person to person. Researchers found that people with more conservative thoughts are more responsive to negative environments than their counterparts. These people are more likely to support policies that minimise harmful incidents (e.g., anti-refugees) or promote their country’s stability (e.g., support military enforcement, support local businesses). In contrast, people with more liberal thoughts are more willing to support policies that provide social welfare (e.g., free access to medical care) or challenge conventional use of power and authority (e.g., rehabilitation of criminals). It is important to note that the negative bias is evolutionarily beneficial, and everyone has it to a certain degree. People who live in more conflict-ridden and more dangerous environments may show more negative biases compared to people who live in a safer environment. In summary, conservatism and liberalism are relative; they represent tendencies of thinking and behaviours, rather than absolute, unchanging characteristics. Those tendencies are rooted in individual psychological and physiological differences. However, they are also shaped by the cultural context and responsive to situational forces as well as group norms and leadership. In diverse environments, both conservatism and liberalism can be beneficial to a country. - Gi Chonu Rioting occurring after a football match is not an uncommon phenomenon. Longstanding hostility amongst football fan groups is a tradition worldwide. Hooliganism is a term that describes violent behaviour perpetrated by football spectators, and we find the phenomenon occurring across the globe. In extreme circumstances, death can be an outcome of such riots. For example, during Honduras’ 1969 World Cup qualification, 2,100 people died. In Indonesia, the country where I lived previously, hostility between two fan groups occurs between groups from two cities that are close together.

The most contemporary case of violent football riots in Indonesia resulted in the death of Haringga Sirila (23 years old) on 23 September 2018. The young man was a big fan of Persija, a football team of Jakarta. The violent hostility between the two fan groups remains a deep tradition, with seven people from the two groups having died since 2012. This hostility is not an isolated case and similar cases also occur in other cities around the country. However, the question arises: Why do they strike? One line of work examines violent behaviour perpetrated by a group or a mass as “Amok” (or ‘running amok’): an analysis with historical roots in the Malay tradition. A study conducted by Manuel L. Saint Martin of the University of Southern California, attributed this kind of mass violence in South East Asia to mental and personality disorders and extreme psychological distress. Interpreting mass violence as ‘running amok’ is an explanation that points to feelings of frustration and violence as the effect of social or psychological pressure. But this explanation seems inappropriate to explain football fans’ rioting. So what drives physical violence amongst football fans? Another type of explanation draws on the psychology of groups. Social psychological research has shown that we have two kinds of identity: personal identity, representing our uniqueness and what distinguishes us from others (I am different from other people), and social identity, usually called a group identity. A social identity allows us to associate and bond with other people (e.g., ‘I am Australian’, or ‘I am a fan of this club’). How are these personal and social identities related to the violence occurring amongst football fans? A great deal of research is exploring this question. One answer points to the relationship between personal and social identity, a concept called Identity fusion. It is a very deep sense of oneness with a group and its individual members that motivate pro-group behaviours - even personally costly ones. The feelings of identity fusion are not just being strongly bonded with a group, but it is having deep emotional ties with other group members. These bonds are similar to familial bonds. Familial bonding usually occurs in a narrow context (e.g., with members of our nuclear family), but the concept of fusion can be extended to a larger group such as national group, religious group and of course, a football fan group. But how can the feeling of oneness lead to intergroup violence? Work on identity fusion suggests a number of factors facilitate the connection between the sense of oneness and violence. For example, arousal has been established as a catalyst for those who have strong feelings of oneness with the group to engage in extreme behaviour. An experiment involving 245 students in Spain, showed that in a dodgeball game, stimulating arousal within the group resulted in more extreme behaviour on behalf of his/her group. A second factor is called the personal agency principle, whereby an individual feels that he/she represents the group and is compelled to act on behalf of the group. Of course, not all pro-group actions are violent! But when people who feel fused with a group feel frustrated or threatened, the sense of being compelled to act even if extreme actions are needed means violence is more of a risk. The death of a football fan in a riot, as in the case of Haringga, can be explained in this way. In a pre-match situation, the crowds in a stadium can create arousal, increasing the risk of violent behaviour for those whose personal identity is fused to the group, and who experience a sense of personal agency alongside collective threat or frustration. In addition, previous studies show that shared painful past experience amongst group members may also play a role. Along with our colleagues (Martha Newson, Harvey Whitehouse, and Vici Sofiana Putera), we collected the data from 100 people of two conflicting fan groups in Indonesia (Bandung team and Jakarta team). Our focus was on the extent to which the shared painful experiences with fellow members can be a catalyst for the tendency to engage in violent behaviour on behalf of the group. We found that the tendency to act extremely is more likely when a person had experienced feelings of oneness with the group, and especially when the members shared a painful past experience. In football rivalries, we know that, the fans of the two teams competing with each other, have shared the painful experience of violence from the other group. When one group’s violence promotes the second group’s fusion, which in turn is linked to their extremism or violence, a vicious cycle is initiated. What can be done to stop violence among highly fused fans? Identity fusion seems to rely on very strong ties, that are almost impossible to defuse. So, an “extreme’ approach to preventing violent associated with identity fusion is to dissolve the group itself. But, in most cases, this approach cannot be implemented. A more feasible approach may be changing the norm of the fan groups – i.e., their standards or rules for pro-group action. Some football fans have norms of supporting hostility and violence. The key may be to change these norms, with the help of the football team itself and the football regulation boards, to promote positive norms. One example would be using the match as a way to raise funds for natural disaster victims around the country, or for children impacted by cancer, is a potential way to slowly and sustainably change the hostile norm associated with the match with a caring norm. The view of the competition is shifted so it is not only about the number of goals scored by the players, but also about the funds collected by the fans. This would strengthen the injunctive norm that football fans contribute positively to society. Similarly, many positive values such as fairness, peace and justice can be clearly seen in good sportsmanship, and if we promote these values, we can help fans groups to also extend these values to their rival teams. - Susilo Wibisono & Whinda Yustisia *The article is a version of an article written for and published by The Conversation Indonesia, on Sept 28, 2018. I’ve written before about different types of domestic abuse. New research shows that when people subscribe to traditional social norms about gender and romance, they may be more vulnerable to such abuse. How traditional gender norms can promote domestic abuse Gender norms highlight the expected or typical behaviour of a person based on their gender. Traditional gender norms hold men as strong, dominant protectors and women as kind, nurturing caregivers. Gender norms don’t consider gender diversity or fluidity. Although such norms seem positive—emphasising chivalry towards women, for example—these ideals are restrictive of both men and women. Women’s perceived competence may be lowered, and men may be less able to express their emotions and vulnerability. Many people who hold traditional views of gender have loving, equal relationships. For others, gender norms can promote a power imbalance that may manifest as abuse within relationships. Research has shown that women who endorse traditional gender norms are more likely to experience intimate partner violence in their romantic relationships. The same is true for people who believe in traditional romantic beliefs and norms. Why subscribing to romantic norms makes some women vulnerable to abuse Traditional romantic norms emphasise the importance of being in a relationship and promote the ideals of love at first sight, one true love, and love conquers all. These ideals are ever present in Western cultures. Even in early childhood, Disney movies and fairy tales promote love at first sight and the power of love to triumph over all obstacles to an unrealistic degree. Similar messages persist through teen and adult romance novels and films. Contrary to intuition, women who accept such romantic norms are actually more likely to experience abuse within their romantic relationships. When internalised, romantic norms may encourage women, in particular, to view their romantic relationship’s success or failure as a reflection of their own self-worth. That’s when such norms can become dangerous. Accepting romantic norms may motivate people to ignore or romanticise the warning signs of an abusive relationship. Possessiveness and jealousy can be easily reframed as romantic rather than controlling. Popular media Twilight and 50 Shades of Grey, for example, both strongly romanticise controlling behaviours as a sign of passion and commitment. Characters in both series express the desire to restrict the behaviour of their love interest for reasons motivated by jealousy and possessiveness. But acting on jealousy in this way by controlling who your partner spends time with and when, is a form of abuse. Where do we go from here? Differences and complementarity can lead to mutual respect and care. Vulnerability can be a part of intimacy. In contrast, abuse in romantic relationships is typically about control. Traditional gender norms, and idealised romantic norms provide a framework that can be used to justify or romanticise control and power imbalances. As we move forward we need to challenge our understanding of romance and gender. We need to focus on trust and equality as the foundations of healthy romantic relationships. - Kiara Minto Why do people do things that harm others? Socially harmful behaviours, like discrimination and hate speech, are still common in modern society. But where do these behaviours come from? According to self-determination theory, pro-social behaviours (like tolerance and fairness) come from within, because we have a personal desire to engage in them. In contrast, harmful acts are normally motivated by an external source, such as social pressure to conform. For example, school bullying may be encouraged by those classmates that intimidate other students. In order to avoid being bullied, and also to become close to the popular children in school, some kids may also start bullying others. To summarise, helping other people gives us real pleasure and enjoyment, while harming others only brings recognition from others and helps achieve our goals.

Even though discrimination is not truly motivated by our own values and beliefs, from this perspective, is it possible that harmful behaviour can become a part of our identity and represent who we really are? Discrimination can be a consequence of social norms One cause of discrimination are the social norms associated with the groups we belong to. In an attempt to fit into society, we follow the norms of our own groups. These norms, however, are not always oriented to benefitting the interests of people in other groups. For example, an organisation with racist norms that dictate choosing job candidates that belong to the Caucasian ethnic group rather than choosing based on qualifications, will motivate the recruiter to follow these norms and to discriminate against certain ethnic groups. We may follow discriminatory norms in order to feel we fit in with our group, or that doing so promotes our group’s values or goals. When a behaviour is considered normal in groups we belong to, but is actually inconsistent with what we personally believe in, this creates a sense of conflict within our identity. Compartmentalisation helps us deal with inner conflict This feeling of contradiction between our values and our situation reflects an underlying resistance to engage in harmful actions. For example, a recruiter who personally believes that job candidates should be hired based on their merit will feel an internal conflict when following the firm’s discriminatory norm. In response to inner conflict, we tend to separate the harmful (e.g., discriminatory) behaviour from other life situations and contexts. This is called compartmentalisation. Going back to the example where Caucasian candidates are preferred when hiring, this would mean that the conflicted recruiter would restrict ethnic discrimination behaviour only to work situations and would not generalise it to other life contexts. By using this compartmentalisation strategy, the harmful social behaviour is restricted to a particular life context and does not become representative of the entire person. From the self-determination perspective, compartmentalisation also protects one’s identity from negative evaluation. People do not enjoy discriminating against others Many people want to believe that human nature is inherently good, and that no one would willingly harm others and feel good about themselves. The results of our studies confirm that people who discriminate do not necessarily enjoy their actions harming others. Rather, they are more likely to feel an internal conflict when discriminating. On this positive note, we conclude that harmful behaviors are somewhat more difficult to accept as a part of who we are. Although specific life situations may sometimes dictate discriminatory actions, they generally bring less pleasure and enjoyment. Instead, causing harm to others evokes feelings of internal conflict and dissociation, which the majority of us will try to minimise. - Guest post by Ksenia Sukhanova and Catherine Amiot, Université du Québec à Montréal *** Read full article: Amiot, C. E., Louis, W. R., Bourdeau, S., & Maalouf, O. (2017). Can harmful intergroup behaviors truly represent the self?: The impact of harmful and prosocial normative behaviors on intra-individual conflict and compartmentalization. Self and Identity, 1-29.

Climate change is real, so why the controversy and debate? Often the way science and ideas are communicated affects the response they motivate.

In this interview, I argue climate science communication should be informed by the psychology of persuasion and communication in conflict. I talk through concrete examples of effective and ineffective messaging and the key factors to consider. The ideas I present here are relevant for anyone working in science communication or social change. Key points include:

Watch the full interview below:

I'd love to hear your feedback. Please leave a comment or a question below and I'll get back to you.

- Winnifred Louis Eat your five serves of fruit and vegetables! Get your 30 minutes of exercise! Drink responsibly! There’s no shortage of messages telling us how to be healthy. But do we action them? Health habits solidify during young adulthood and have knock-on effects for later life. University students may be particularly vulnerable to forming bad habits. Young people are responsible for their diets for the first time, but also under time pressure and economic strain. University students also experience other pressures, such as peer pressure to drink excessively or to engage in other risky behaviours. So are young people building healthy habits at University? Unfortunately, this does not appear to be the case. Students’ engagement in health behaviours actually declines over the course of their studies. The link between students and excessive drinking is also well-known. If students are so smart, why do they do so many dumb (unhealthy) things? When students identify with the student group, they may act in line with the norms of that group. Because student norms tend to favour unhealthy behaviours, students end up engaging in unhealthy behaviours. In a recent book chapter, we distilled key lessons from social psychology and discussed how these insights could be used to change behaviour.

People engage in behaviours seen to be central or defining of their group Health behaviours are not simply personal choices but rather reflect habits that are part and parcel of belonging to particular groups. These behaviours can have negative or positive consequences depending on which behaviours have become tied up with group membership. As an example, consider how the central role in the national psyche of the full English breakfast or the meat-laden Australian BBQ determines day-to-day food choices and compare this to the classic Mediterranean diet or the abundance of fresh fish and vegetables in Japan. Students often describe behaviours with negative implications for health – such as excess alcohol consumption – as ‘normal’ within the university context. Many have expectations about these norms even before they step foot on campus. So, when students are thinking about themselves as a student, being healthy is not at the forefront of their minds – in fact, the opposite is clearly the case. Efforts to change student behaviour that make student identity salient may backfire because student identity does not promote health behaviour. Those who want to change student behaviour need to encourage students to see themselves in terms of another identity for which healthy behaviour is expected – such as athletic identities – or make health behaviour more central to what it means to be a student. Changing group norms is no easy task If unhealthy behaviours are seen as central to what it means to be a group member – such as students and drinking – group members may be very resistant to attempts to change their behaviour, even if such change would improve their health. Norms themselves are quite complex. They have both a descriptive element (what is commonly done) and a prescriptive element (what should be done). And these two elements don’t always align. For example, students might approve of more responsible drinking but still go out and binge drink anyway! When these descriptive and prescriptive elements are in conflict, people tend to go along with what their group actually does, rather than what their group thinks should be done. So, if people try to change one element without paying attention to the other, these efforts may be ineffective or even counterproductive. If you want to encourage health behaviours, you need to communicate that the group both approves of healthy behaviour and actually engages in that behaviour. Change agents should try to frame identities and norms in ways that communicate that being a student means being healthy. And work with students on health messages to ensure that these are credible and acceptable. We believe that bringing a stronger understanding of how social factors shape students’ choices about their health allows us to unlock the full potential of groups so that these become a positive – rather than a negative – force for students’ health behaviours. Stay tuned for more updates on our progress! - Joanne Smith (Guest blogger and Social Change Lab collaborator) *** Read the full article: Smith, J. R., Louis, W. R., & Tarrant, M. (2017). University students’ social identity and health behaviours. In K. Mavor, M. J. Platow, & B. Bizumic (Eds.), Self and social identity in educational contexts (pp. 159-174). London: Routledge. |

AuthorsAll researchers in the Social Change Lab contribute to the "Do Good" blog. Click the author's name at the bottom of any post to learn more about their research or get in touch. Categories

All

Archive

July 2024

|

Social Change Lab

Join our mailing list!Click the button below to join our mailing list:

Social Change Lab supports crowdfunding of the research and support for the team! To donate to the lab, please click the button below! (Tax deductible receipts are provided via UQ’s secure donation website.) If you’d like to fund a specific project or student internship, you can also reach out directly!

|

LocationSocial Change Lab

School of Psychology McElwain Building The University of Queensland St Lucia, QLD 4072 Australia |

Check out our Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2017

RSS Feed

RSS Feed