|

This post is a departure from our usual blog format of short pieces about research and practice in our group: it's a personal reflection (from Winnifred Louis) on Donald Taylor as a person, and his scholarship and influence.

I was a masters student with Don starting in 1994, when I wrote a thesis on reactions to gender discrimination at McGill University. I then went on to complete my PhD with him from 1996, looking at reactions to English-French conflict in Quebec. He generously involved me in projects and papers on attitudes to immigrants in South Africa and heritage language retention in Quebec, and we worked together on a paper on responses to 9/11, and then on responses to terrorism. After I graduated, he cheered me on and welcomed my students’ visits. He passed away from cancer last month, in November 2021. I can’t possibly express how much I love the guy and what he meant to me, but here is a short list of some of the key things that come to mind. Autonomous students. Like all Don’s students I worked on projects close to my heart and my interests, I didn’t build an empire for him. He used to laugh at people who would take credit for their students’ work and say, “good supervision is when you set it up for students to steal *your* ideas!”. Students would come in rambling and riffing, and he’d point them to the relevant literatures and send them off to forage, then when they came back, distill their chaotic learnings into hypotheses and a sound research design, and loop them to repeat, as they developed “their” project. Don loved the diverse research that this approach brought to him. And when the PhD students finished, he set them up to develop new collaborations, so they could establish themselves as independent scholars, instead of milking their PhD, not matter how successful it was. “If I couldn’t totally change my research focus every seven years I wouldn’t be here,” he said. Incredible hulk. Don was a guy who was broad-shouldered and beefy, a football and hockey player at the varsity level. His fashion sense was erratic - in our first meetings, I was alarmed by his 70s style, with shirt open to mid chest, and gold chains nestling in his chest hair. I thought this must mean he was terribly sexist – and some of his unsavory comments didn’t help allay that fear, talking about how the girls chased the players on varsity teams, or how he and a friend in grad school had planned to start a university so they could fool around with the undergrad girls. He used to wear an Australian Akubra cowboy hat and oilskins - he liked the look - and signed an email to me in 2020 with a smiling emoji wearing a cowboy hat. Even in our last ftf meeting, when he was in his late 70s, he turned up in his Akubra, and told me with glee how he’d been captured by the cult of cross-fit, referring to himself as a gym-jockey. But what I quickly learned was that for all this flamboyance - he loved attention, he loved sports, he loved physical challenges – Don was very far from the stereotypes of toxic masculinity, insensitive or domineering. Instead, he was a gentle and often a humble person. The more shy and powerless the other person, the more Don was respectful and kind, quick to self-deprecate or joke, hunching down and tilting his head, attentively listening and learning. Support for square pegs. The transition from football scholarship to academic research saw Don scrape over class barriers that were very much alive in the 1950s and 1960s. Maybe that was why he was always ready to support square pegs to work their way into the system. Anyone who battled their way through was liable to find him ready to hold the door open into his lab – female students, or people from minority ethnic groups, at times when that was still unusual at McGill. Refugees from Iran and Rwanda. Myself as a lesbian, at a time when I didn’t know anyone at all, in all of academic psychology, who was openly gay. Quirky characters with narrow focus, and people raging against the system. He savoured the diversity and the joyfulness of people whooshing out the doors of his lab with skills and drive. “You’ve got to launch them!,” he said to me on mentoring grad students. “You don’t just churn them out, you launch them!” Passion for teaching. At the same time Don loved and respected undergraduate teaching. Famously he never missed a class in his 40+ years of undergrad teaching, even the day after a hockey game where he had 20 stitches to his face. “You will influence many more people through your teaching than through your research,” he used to say to me and others. He would teach huge classes of 700, but always remembered to see the students as individual people. He would discard the scheduled lecture content to respond to climactic events, like 9/11. He would talk to students and he would listen to them. I used to fear public speaking tremendously myself, to the point of blushing, trembling, and cracking voice, complete overwhelm. “You feel fear as a teacher when you are thinking about yourself,” he said to me kindly. “Try to think about your students instead - how much you want them to learn what you’re saying. Think about the content, and how much you love the content, and why you care!” Good advice - he was an excellent public speaker. “You’ve got to live for the anecdote!,” he used to say. Don was also a story-teller who would mercilessly blow the time limits of his talks, and of his classes, in order to digress to stories that made people laugh, think and act differently. But he was also someone who, in his everyday life and his career, would turn to go down less travelled paths, stop to hear from unexpected people, and choose something strange and different whenever the choice was offered. “Live for the anecdote!,” he would say. Don’t get stuck in a rut. Don’t pass by the opportunity that won’t come again. Live with panache! Make a difference! Don’s career was impressive in many respects, but perhaps most unusual in showing his long-term commitment to sweeping social change around the world. For five years as a PhD student, I flew up annually on seven-seater planes to Kangiqsujuaq, a tiny village in Arctic Quebec, 100s of kilometers above the treeline. I was part of a 30 year rotating team of students and RAs who learned about the North and contributed to research co-designed with Indigenous Inuit communities on language, identity, and social attitudes. Another time, with Don, I contributed to a special issue in memory of William Robinson, a language scholar who was retiring, and who lamented that at the close of his career he was disappointed that he had not overthrown the class system in the UK. Don and I laughed – but Don applauded that he had never lowered his sights. “They just don’t get it!,” Don used to say irritably, skimming the latest incremental, trivial study, or self-focused theoretical micro-dispute. The world was full of huge problems, with real people struggling - *these* problems needed attention and theorising. The big problems, the big picture – his students were always pushed to consider how our research fit into these categories. Moving beyond the WEIRD context before it was labelled as such, Don introduced me and dozens of other students and collaborators to challenges facing disadvantaged communities, and encouraged us to study them – by going there, by being there, by listening, by working with them, by following their agendas. He supported scholars from the disadvantaged communities and in the global south, and amplified their voices and their theorising. Pragmatism and sober-minded clarity. He was woke before there was wokeness, but at the same time, he would never have presumed that others would feel the same way, or waste time being surprised if others rejected those values. Don was always really clear about the academia that we worked in as not valuing social change or positive benefits to communities, and even being hostile to them. Maybe that’s not true now in some cases – I hope so. But I still teach my students what Don taught me in the 1990s. He said, you need two lines of research: a mainstream one using mainstream methods published in mainstream journals – this will get you your job, tenure and promotion. It will get you grants. The other work, your applied work, you have to be ready to have dismissed. It has to be for the benefit of communities, so it may be slower, or grind to a halt, or blow apart due to politics. Maybe there will be no academic outcomes for years, or at all. Publication may be relegated to journals and conferences that powerful gatekeepers don’t care about at all, or even see as harmful. (In my own career, a former Head of School, which is like a department chair, once remarked, “If you’re going to publish in the Journal of Applied Social Psychology, why publish at all?”) So you have to do both mainstream and applied work, to secure your future, Don would say. You have to publish. But it’s not *just* about job security. Applied work will make you a better theoretician, Don said – more alive to complexity, more aware of received wisdom that’s not actually true. Go outside the box. Look back from the outside. And also: theorising and experiments will strengthen your contribution to application – they will help to untangle causality. And they will credential you to go out to communities and speak to policy makers. Money matters. In the same pragmatic vein, Don was always keenly aware that money matters. He learned from Wally Lambert, a social psychologist at McGill famous for his research and his own memorable stories of cheap-skatedness, to never stay at conference hotels, as being too expensive and a ripoff to the taxpayer. Over the course of his career, Don used to reflect with smugness, he’d directed thousands of dollars from his grants towards research participants and RAs, by staying in shared rooms at hostels when he travelled, or with friends, instead of living it up in luxury. He loved the vibe as well – or at least, male graduate students and RAs that’d shared with him brought back stories of Don sitting around in his boxers playing the guitar, and late nights talking theory and drinking beer. More nefariously, in his later career Don used to sneak into conferences to give his research talks without paying to register for them – something that puzzled and exasperated the conference organising teams, often made up of his former students and friends. “These are ridiculously expensive,” he said at one point when I asked him about it - I guess he decided other student and research expenses were more worthy. It’s a choice he felt was legitimate for him to make, which tells you a lot about him. Bend the rules and make them work for you. Don understood the importance of institutions, and cultivated relationships with policy-makers for immigration, language, and race relations carefully all his career. He also kept a vigilant eye on university politics. But he despised bureaucracy and institutional politicking. So he was always ready to bend the rules. He helped set up courses at McGill for Inuttitut education that effectively became offered in intensives, creating a path that allowed Inuit students to credential themselves as teachers with less difficulty. “What kind of names are these?,” the Dean asked him in bewilderment at one point, peering at the -iaq and -miq graduands – unexpected lists of names ending in q and k. Don used to laugh happily to us as he recalled getting the system to work for the students this way. Look for ways to make what you want to do fit a label the system can live with. Look the authorities in the eye and smile blandly. Hold the door open to let others through. Human at work. All of these things influenced me, and they help me now, and my students too, but the thing that speaks most loudly to my heart now is that long before the term was fashionable, Don was ‘human at work’ – he was authentic and real, and not just defined by his job. He spoke to us about his family, and he asked about mine. He came to my wedding. He played music, and sports, and coached kids’ sports, and took time off for holidays with his wife and kids – and he encouraged us to do the same: take time off for other things. Be real. Have friends and family. “It’s different now,” we used to say to him – we grad students of the 1990s – “it’s too competitive, you’ve got to work all the time and stack up publications, you can’t get by and take weekends off”. “I worry that’s true,” he used to say. But work expands to fill the time you give it. Have the best career you can, within the boundaries you set. Don had a great career. He won national awards for teaching, for research, and for service. He was also deeply loved, as much as anyone else I know or more so. At a symposium we had in honour of Don at the Canadian Psychological Association conference in 2016, people came from all over the world to celebrate his influence and research. I came myself from Australia. He was utterly astonished – he was completely flabbergasted that so many people would go to so much effort to celebrate him and his work. I will close this tribute, as I closed the talk on the day, with these words: Thank you Don! For tremendous support personally & professionally for more than 20 years …For an inspiring vision of a great life filled with joyful curiosity, research, family, sports, music, and activism …For moral indignation always translated with determination and humour into action and alliances, …For boundless scepticism about authorities and bureaucracy, but tremendous faith in teaching, science, and possibilities, … And for highlighting the value of living for the anecdote ! *** Other tributes to Don for those who knew him or are curious: In his own words

Others’ words

12 Comments

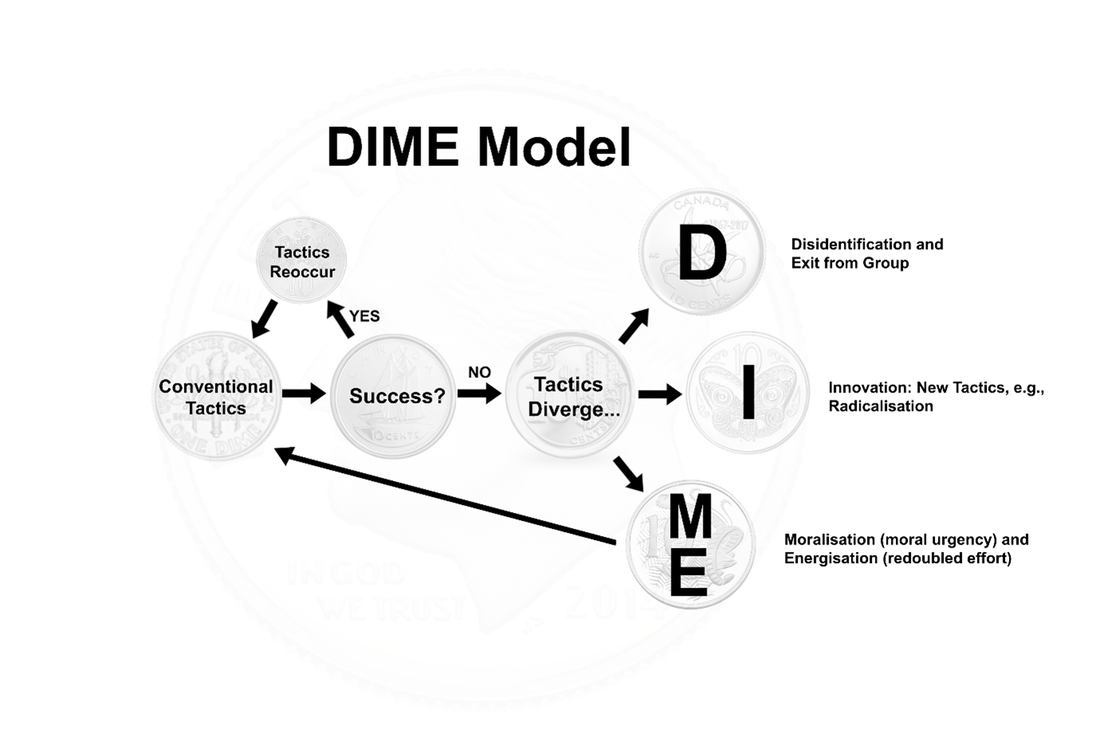

What are the key ingredients for successfully developing large-scale cross-disciplinary research proposals? What’s required for a team to successfully work together at the proposal development stage? Here we provide seven lessons based on our experience, divided into:

Team characteristics Lesson 1: Invite a mix of new blood and established experience. It is useful to have team members at various stages of their careers, as well as researchers who have worked together previously and those who have never met before. It can work well to have clusters of researchers who have worked intensively within the cluster, but who are new to each other across clusters. Lesson 2: Foster convergence readiness. Prior experience in cross-disciplinary collaboration can enhance the dynamics of preparing a proposal by combining deep expertise in a discipline with the ability to see how the pieces fit together. Lesson 3: Encourage open questioning. One of the main difficulties with cross-disciplinary collaboration is the longer runway required for takeoff. It takes time to understand other disciplines and develop trusting relationships. This involves listening generously and asking a lot of questions. In addition, specialized disciplinary languages do not translate across all fields, so plain language is needed. To achieve such an environment, we recruit team members with confidence but without big egos. Confidence engenders the security needed to be vulnerable and ask questions, as well as to be comfortable in the unknown. On the other hand, big egos can result in repression of other team members’ perspectives. Structuring the grant proposal writing process Lesson 4: Use a mixture of ways to communicate and work together. Big group conversations are important for coherence, but small working groups are more effective at getting things done. Share the ideas generated in small groups with regular updates and survey questions. In addition, cross-pollinate with boundary-spanners across teams, who may be the leaders of the sub-teams, or individuals liaising across two or more sub-teams. Further, actively weave together thinking and writing. While it can be tempting (and easy) to spend a lot of time talking with each other, writing is a powerful way of communicating and brings much needed clarity to the thinking process. Lesson 5: Shift the academic culture. The collaboration-driven convergence culture stands in sharp contrast to traditional academic culture mired in competition and silos. Researchers need to recognize the interdependence between their success, their colleagues’ success, and the success of the overall research team. Women have an important role to play in shifting the academic culture and fostering collaboration, sharing, and connecting. Lesson 6: Allow plenty of time for team development. Teams need time to form, storm, norm, and finally perform. Take into account the fact that everyone has multiple obligations to juggle, as well as needing downtime at the end of the year and for vacations. Lesson 7: Plan for research implementation and broader impact. Key to research making a difference is long-term partnerships with those who are likely to use the research. For instance, research seeking to contribute to racial equity will only be effective if the researchers already have relevant long-term partnerships, for example with minority-serving institutions. Conclusion This blog post is based on our recent experience developing a proposal for the US National Science Foundation’s Sustainable Regional Systems-Research Networks solicitation. Our five-year $15 million project involved ten academic institutes, with a wide spectrum of disciplines, and 30 other stakeholder groups including state and city governments, non-governmental organizations, and industry partners. What have your experiences been with developing proposals for large-scale cross-disciplinary research projects? What lessons have you have learnt? What roses (strengths), buds (potential) and thorns (challenges) could you share with the community? - By Gemma Jiang, Jin Wen, and Simi Hoque This post was previously published on the Integration and Implementation Insights Blog Biography: Gemma Jiang PhD is the Founding Director of the Organizational Innovation Lab in the Swanson School of Engineering, as well as the founding host of the Pitt u.lab hub and the Adaptive Space at the University of Pittsburgh in the USA. She applies complexity leadership theory, social network analysis, and a suite of facilitation methods to enable transdisciplinary teams to converge upon solutions for challenges of societal importance. Biography: Jin Wen PhD is a Professor in the Department of Civil, Architectural, and Environmental Engineering at Drexel University in Philadelphia, USA. She has about twenty-years of experience in the sustainable building field and has taken several leadership roles in directing large scale collaborative research projects. Biography: Simi Hoque PhD is an associate professor in Architectural Engineering at Drexel University in Philadelphia, USA. Her expertise is in sustainable building design and computational modeling to characterize urban resilience. She is deeply invested in promoting women and girls in engineering.  Members of the University of Queensland Social Change Lab posed for our annual end of year photo. In the COVID era, many lab members were Zooming in…. From left to right in person: Morgana, Zahra, Hema, and Winnifred. From left to right in the Zoom: Top row: Mai, Susilo, and Eunike; middle row Robyn, Kiara, and Ruby; last row: Madeleine, Zoe, and Leila. I want to start, as usual, by acknowledging our group’s successes: In 2020, the lab saw Robyn Gulliver and Gi Chonu awarded their PhD theses - whoohoo! Susilo Wibisono, Zahra Mirnajafi, and Kiara Minto also submitted their theses for review, so woohoo! in advance. J Well done everyone! For their next steps, Susilo and Kiara are still canvassing their options; Robyn is about to start a post doc on collective action at HKU with Christian Chan; Zahra is going to take up a one year post doc on volunteer organisations in Iran with Jolanda Jetten; and Gi has secured a stats teaching gig at the Singapore campus of James Cook Uni, after moving to Singapore with her family (in the middle of a pandemic!). Well done all round! While we are sorry to see her go, we are delighted to say that Morgana Lizzio-Wilson, who has been a post doc on the collective action grant and voluntary assisted dying grants in 2020, has been offered a two year post doc at Flinders with Emma Thomas. What a wonderful opportunity! Well done Morgana! She will be moving to Adelaide in March. Meanwhile, we also welcomed to the lab (virtually) Leila Eisner, who secured a post doc from the Swiss government to work with me on norms and collective action. She has unfortunately been prevented from moving to Brisbane in person due to COVID. Here is hoping that the development of vaccines will re-permit international travel and scholarship later this year … but in the mean time, we welcome Leila to our meetings when the time difference permits! 2020 also saw many other students working through their other milestones, including Gi, Zahra, Kiara, Susilo, and Robyn who finished their thesis reviews (and in fact, as mentioned above, submitted!). Eunike Mutiara was confirmed successfully after her first year on a project in genocide studies with Annie Pohlman in the School of Languages and Cultures at UQ and me. Hannibal, Liberty and Robin are moving into their final year, and so is Tulsi (who has a final two years due to working part time). I also want to pass on a special thank you to our volunteers and visitors for the social change lab in 2019, including Ruby Green, Hema Selvanathan, Jo Brown, Mai Tanjitpiyanond, Lily Davidson, Celeste Walsh, Raine Vickers-Jones, and Peter Benton, along with our summer scholars Mina Fu, Madeleine Hersey, and Zoe Gath. Thank you everyone! And here’s hoping that 2021 is equally fun and social, as well as healthy, happy and productive for us and for the group! Other news of 2020 engagement and impact We had our normal collective plethora of journal articles (see our publications page) but of course conferences this year were greatly affected by COVID. Due to COVID, I missed out on my sabbatical visits to Indonesia, Chile, New Zealand, and the USA, and I have now restarted teaching. However, I did get to participate in and listen to a variety of fun Zoom forums. The lab organised an interesting symposium online on The Social Psychology of Violence and I gave an online keynote address to the International Zoo Educators’ (IZE) annual conference in October 2020. As part of the COVID pandemic, I developed some new resources online (listed here). I also joined an immense research project, https://psycorona.org/ . It was an incredible lesson in the possibilities for collaboration and agile research, and I am sure that the harvest will be reaped by scholars for many years to come. In regards to pubs, I was excited in 2020 by finally getting this theory piece out, which in addition to other very fun riffing, at last published the DIME model formally. The first empirical paper was also finally accepted in Psychological Science – whoohoo! It is still not out though, and the other major DIME paper is still working its way through the process of being rejected excruciatingly slowly by all the best journals. :) In other news, our lab has continued to work to develop open science practices in 2020 and to establish consistency in pre-registration, online data sharing, transparency regarding analyses, and commitment to open access. I think for us as for the field, progress is steady! Socialchangelab.net in 2021 Within the lab, Kiara Minto has been working to solicit, edit, and publish the blog posts, and to encourage creation and updating of our pages. Thank you Kiara for all your great work last year with our inhouse writers, our guest bloggers, and the site! We continue to welcome each new reader of the blogs and the lab with enthusiasm, and if you have ideas for guest blogging, by all means contact me to discuss them. I also am still active for work on Twitter, and I hope that you will follow @WlouisUQ and @socialchangelab if you are on Twitter yourself. In 2020 we also started a facebook page: https://www.facebook.com/The-Social-Change-Lab-research-by-Winnifred-Louis-and-team-109966340687649/ . I am still getting the hang of it, but I invite those of you who are still on fb to consider following the page. Looking ahead, I am working with the IZE association to develop some cool online content around my ‘effective environmental communication’ talks. Although this may end up being behind a pay wall for zoo educators, I look forward to seeing how the professionals do it. This is because I am also working (particularly with the assistance of Robyn Gulliver) to develop some new content that will be available to all, in a project to download my brain to the internet. What could go wrong? ;) What the new year holds: In 2021, at the moment I have no plans for actual travel, and so it’s all online meetings all the time. However, I do frivol around with zoom a lot and I hope that people will contact me for meetings and talks if interested. I will be participating online at the SPSP conference with a data blitz sessions and in a symposium led by Ana Leal. At UQ, I’ll be teaching third year stats and Applied Social Psychology (a fourth year elective) in S1 and S2 respectively, which I really look forward to. I am also presently trying to develop new lines of work and grant apps on trajectories of stalemates, gridlock and polarisation. I welcome new riffing and contacts on any of these. I have some big grant apps out with colleagues but who knows if any can proceed. This year I also am open to new expressions of interest from honours students and PhD students. While my primary focus is still on writing and working through my backlog of data, I’ll be considering new students in 2021. There is some info on working with me here. A list of our 2020 papers is given below, and if you are interested in a copy of any of these, please do just ask. All the best from our team, Winnifred Louis Asún, R. A., Rdz-Navarro, K., Zúñiga, C. & Louis, W. (2020). Modelling the mediating effect of multiple emotions in a cycle of territorial protests. Social Movement Studies, DOI: 10.1080/14742837.2020.1867093 . Published online 30 December 2020. Amiot, C. E., Lizzio-Wilson, M., Louis, W. R., & Thomas, E. F. (2020). Bringing together humanistic and intergroup perspectives to build a model of internalisation of normative social harm-doing. European Journal of Social Psychology, 50(3), 485-504. DOI: 10.1002/ejsp.2659. Chapman, C. M., Masser, B. M., & Louis, W. R. (2020). Identity motives in charitable giving: Explanations for charity preferences from a global donor survey. Psychology & Marketing, 37, 1277-1291. DOI: 10.1002/mar.21362. Fielding, K. S., & Louis, W. R. (2020). The role of social norms in communicating about climate change. In D. C. Holmes & L. M. Richardson (Eds.), Research Handbook on Communicating Climate Change, pp. 106-115. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing. González, R., Álvarez, B., Manzi, J., Varela, M., Frigolett, C., Livingstone, A., Louis, W., Carvacho, H., Castro, D., Cheyre, M., Cornejo, M., Jiménez-Moya, G., Rocha, C., Valdenegro, D. (2020). The role of family in the intergenerational transmission of collective action. Social Psychological and Personality Science. Published online 19/8/20 https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550620949378 . Hornsey, M. J., Chapman, C. M., Mangan, H., La Macchia, S., & Gillespie, N. (2020). The moral disillusionment model of organizational transgressions: Ethical transgressions trigger more negative reactions from consumers when committed by nonprofits. Journal of Business Ethics. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10551-020-04492-7 Kahdim, N., Amiot, C., & Louis, W. R. (2020). Applying the Self-Determination Theory continuum to unhealthy eating: Consequences on well-being and behavioral frequency. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 50(7), 381-393. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12667 . Lantos, D., Lau, Y. H., Louis, W., & Molenberghs, P. (2020). The neural mechanisms of threat and reconciliation efforts between Muslims and Non-Muslims. Social Neuroscience. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470919.2020.1754287 Louis, W. R., Thomas, E. F., McGarty, C., Lizzio-Wilson, M., Amiot, C., & Moghaddam, F. M. (2020). The volatility of collective action: Theoretical analysis and empirical data. Political Psychology. Published online 23 June 2020 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/pops.12671?af=R . Minto, K., Masser, B. M., & Louis, W. R. (2020). Identifying non-physical intimate partner violence in relationships: the role of beliefs and schemas. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. Published online 10/7/20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520938505 Selvanathan, H. P., Lickel, B., & Dasgupta, N. (2020). An integrative framework on the impact of allies: How identity‐based needs influence intergroup solidarity and social movements. European Journal of Social Psychology. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/ejsp.2697 Collective action is a key process through which people try to achieve social change (e.g., School Strike 4 Climate, Black Lives Matter) or to defend the status quo. Members of social movements use a range of conventional tactics (like petitions and rallies) and radical tactics (like blockades and violence) in pursuit of their goals. In this blog post, we’re writing to introduce DIME, which seeks to model activists’ divergence in tactics. The theoretical model is published in an article on “The volatility of collective action: Theoretical analysis and empirical data”, published online here in Advances in Political Psychology. The model is named after a dime, which is a small ten cent coin in some Western currencies. In English the expressions to “stop on a dime” and “turn on a dime” both communicate an abrupt change of direction or speed. With the DIME model (Figure 1; adapted from Louis et al., 2020, p. 60), our goal was to consider the volatility of collective action, and to put forward the idea that failure diversifies social movements because the collective actors diverge onto distinct and mutually contradictory trajectories. Specifically, the DIME model proposes that after success collective actors generally persist in the original tactics. After failure, however, some actors would Disidentify (losing commitment and ultimately leaving a group). Others would seek to Innovate, leading to trajectories away from the failing tactics that could include radicalisation and deradicalisation. And a third group might double down on their pre-existing attitudes and actions, showing Moralisation, greater moral urgency and conviction, and Energisation, a desire to ramp up the pace and intensity of the existing tactics. We think these responses can all co-occur, but since they are to some extent contradictory (particularly disidentification and moralization/energization), the patterns are often masked within any one sample. They can be teased apart using person-centered analyses that look for groups of respondents with different associations among variables. Another approach could be comparing different types of participants (like people who are more and less committed to a cause) where based on past work we would expect that all three of the responses might emerge as distinct. The disidentification trajectory – getting demotivated and dropping out – has been understudied in collective action, and for groups more broadly (but see Blackwood & Louis, 2012; Becker & Tausch, 2014). A major task for leaders and committed activists is to try to reduce the likelihood of others’ disidentification by creating narratives that sustain commitment to the group in the face of failure. Inexperienced activists, those with high expectations of efficacy, and those with lower levels of identification with the cause may all be more likely to follow a disidentification or exit path. Some that drop out, furthermore, may develop hostility towards the cause they left behind. A challenge for the movement therefore is to manage the bitterness and burnout of former members. The moralization/energization path is likely to be the default path for those who were more committed to the group. In the face of obstacles, these group members will ramp up their commitment. But for how long? Attributions regarding the reason for the failure of the initial action are likely to influence the duration of persistence, we suspect: those with beliefs that the movement can grow and would be more effective if it grew may stay committed for a longer time, for example. In contrast, attributions that failures are due to decision-makers’ corruption or opponents’ intractability may lay the groundwork for taking an innovation pathway. A challenge for the leadership and movement is to understand the reasons for the movement failures as they occur, and to communicate accurate and motivating theories of change that sustain mobilisation. Finally, the innovation path as we conceive it may lead from conventional to radical action (radicalisation), or from radical back to conventional (deradicalisation). It may also lead away from political action altogether, towards more internally focused solidarity and support for ingroup members, or towards movements of creative truth-telling and art. There may be individual difference factors that promote this pathway, but it is also a direction where leadership and contestation of the group’s norms would normally take place, as group members dispute whether the innovation is called for and what new forms of action the group should support. The DIME model aims to answer the call to theorise about the volatility of collective action and the dynamic changes that so clearly occur. It also contributes to a growing body of work that is exploring the nature of radicalisation and deradicalisation. We look forward to engaging with other scholars who have a vision of work in this space. - By Professor Winnifred Louis Which charity is most important to you? Why? These are the questions we asked 1,849 people in 117 countries. We analysed their responses to note themes and trends. And we learned a lot about how identities influence charitable giving. Here are four key takeaways: 1. Self vs Other: people can be egoistic or altruistic Some donors (45% of our sample) explained their giving in relation to their ‘self’, talking about their social identities (groups they belong to), values and beliefs, suffering they had experienced, or benefits they had received from the charity as motives for giving. Other donors (59%) explained their giving in relation to ‘others’, talking about the beneficiary’s identities, power, importance, or neediness. 2. Identities influence giving; but which ones? People commonly named both their own identities and beneficiaries’ identities when explaining their charity preferences. Content analyses of beneficiary identities revealed a strong preference for helping children, animals, and sick people. Other types of beneficiaries (e.g., the LGBTIQ community, ex-offenders) were rarely mentioned as the reason for preferring a charity. This suggests that some needy groups are more likely to be helped than others. We were also able to create an inventory of the identities that donors say influence their giving choices. These were different from the identities that fundraisers may assume. The identities most commonly named by donors were based on family, geography, specific charity organisations, religion, friendship groups, and being a human. Charities may wish to make explicit connections with these kinds of identities in their fundraising appeals to help donors see a connection between the cause and one of these important identities. 3. Shared identities are powerful motives for giving A significant minority of donors (around 8%) explicitly mentioned shared identities—the fact that they and the beneficiary both belonged to a group that was important to the donor. This suggests that charities that can highlight a shared identity between potential donors and the organisation’s beneficiaries will be more successful in their fundraising. 4. Motives depend on the beneficiary By analysing the frequency of different motives across different types of charities, we found that donors’ motives are influenced by the beneficiaries in question. Donors were more likely to use self-oriented motives to explain their giving to medical research and religious charities. For these kinds of charities, fundraisers may wish to emphasise relevant identities, personal experiences, and benefits for the donor. On the other hand, donors were more likely to use other-oriented motives to explain giving to social welfare, animal, and international charities. For these kinds of charities, fundraisers may find more traditional empathy-based appeals to be most effective. In sum, this study shows that donors have diverse motives for giving. In particular, both donor and beneficiary identities influence charity preferences. Charities must understand the identities that motivate donors to give to their particular cause or beneficiary, in order to write powerful and effective fundraising campaigns. - Dr Cassandra Chapman *** Read the full article: Chapman, C. M., Masser, B. M., & Louis, W. R. (2020). Identity motives in charitable giving: Explanations for charity preferences from a global donor survey. Psychology & Marketing, 37(9), 1277-1291. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.2136 (or email Cassandra at [email protected] to request a copy of the article) Most of us eat junk foods such as donuts, french fries, and soda. Consuming these types of food is associated with adverse health problems such as obesity, diabetes and cardiovascular diseases. So, what motivates us to eat junk food? The answer, of course, is that our reasons for eating any food vary. For example, we might sometimes eat a chocolate cake for pure pleasure. Yet, at other times we might eat it just to please our friend who is celebrating their birthday. The many types of motivations for unhealthy eating According to self-determination theory, our reasons or motivations for engaging in any behavior differ along a continuum. At one end of the continuum, we find the self-determined motivations, which refer to behaviors motivated by inherent pleasure (e.g., enjoying the taste), important values and lifestyle (e.g., a lifestyle of low physical activity) as well as personal goals (e.g., eating to help social connection). At the other end, we have the non-self-determined motivations indicating behaviors pursued because of an internal sense of pressure (e.g., eating comfort food to reduce stress), external pressures (e.g., pressure to eat birthday cake) or unclear and ambiguous reasons (e.g., no clear reason). Our reasons for eating junk food change during the holidays In our study, we examined these types of motivations in relation to eating unhealthy and junk food. Understanding these motivations for unhealthy eating is important, because when individuals feel self-determined to engage in a behavior, they are more likely to persist in it. Since eating junk food is common and normalized during the Christmas holiday period, this time of the year was chosen for the study. Participants from the United States were followed across time and filled out our questionnaires one month before, during, and one month after the Christmas holidays. Interestingly, we found that some types of motivations for unhealthy eating fluctuated over time, while others stayed stable. During the holiday period, individuals ate unhealthy food because they thought it was important, they wanted to avoid feeling guilty, and they felt pressured by other eating partners. They were also less confused about what motivates them to eat unhealthy food compared to before and after Christmas. So it seems like unhealthy eating was highly salient during the holiday season, and external pressures were playing a strong role. These results show that the social context in which we eat has a strong impact on our reasons for eating unhealthy food. Unhealthy eating is more persistent when it is part of our habits

We also looked at how each type of motivation predicted the amount of unhealthy food individuals consumed. We found that four types of motivations (i.e., values and lifestyle, internal sense of pressure, external pressures and ambiguous reasons) were linked to higher levels of unhealthy food consumption. However, only important values and lifestyle consistent with junk food consumption predicted more unhealthy eating at all times (i.e., before, during and after the holiday period). So, although both self-determined and non-self-determined motivations are associated with eating more junk food, it is when unhealthy eating is part of a person’s important values and lifestyle, that junk food consumption is consistently higher. How do we feel about our motivations for unhealthy eating? These motivations refer to internal thoughts and feelings. So what’s their relationship with psychological well-being? We found that when individuals ate unhealthy food because they found it personally relevant and necessary in a given context, they felt good psychologically. However, if they ate junk food for an unpleasant reason such as a pressure they put on themselves, or if they really couldn’t find a good reason for doing so, they experienced lower psychological well-being. That is consistent with the self-determination approach. But intriguingly, even when feeling that unhealthy eating was part of one’s habits and values increased junk food consumption, eating junk food for this reason was associated with lower well-being.

- By Nada Kadhim Full reference: Kadhim, N., Amiot, C. E., & Louis, W. R. (2020). Applying the self‐determination theory continuum to unhealthy eating: Consequences on well‐being and behavioral frequency. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 50, 381-393. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12667 Consider this troubling fact: an analysis of blogs that focus on denying climate change found that 80% of those blogs got their information from a single primary source. Worse, this source—a single individual who claims to be a “polar bear expert”—is no expert at all; they possess no formal qualifications and have conducted no research on polar bears. No matter what side of the debate you are on, this should concern you. Arguments built on false premises don’t help anyone, regardless of their beliefs or political leanings. But does this sort of widespread misinformation—involving the mere repetition of information across many sources—actually affect people's beliefs? To find out, we asked research participants to read news articles about topics that involved different governmental policies. In one experiment, participants read an article claiming that Japan’s economy would not improve, as well as one or more articles claiming the economy would improve. Unbeknownst to our participants, they were divided into three groups. The first group read four articles claiming the economy was going to improve—and importantly, each of these articles cited a different source. The second group read the same four articles, except in this case, all of the articles cited the same source (just like the climate-change-denying blogs all cite the same “expert”). And to establish a point of comparison for the other groups, the third group of participants read just one article claiming the economy would continue to improve. You might expect that when information is corroborated by multiple independent sources, it is much more likely to sway people’s opinions. If this is the case, then people who read four articles that each cited a unique source should be very certain that Japan’s economy will continue to improve. Furthermore, if people pay attention to the original sources of the information they read, then those who read four articles that all cited exactly the same source should be less certain (because that information was repeated but not corroborated). And, finally, people who read only one article claiming Japan’s economy will improve should be the least certain. Indeed, people were much more likely to believe that Japan’s economy would improve when they heard it from four unique sources than when they read only one article. But, surprisingly, people who read four articles all citing the same source were just as confident in their conclusions. Our participants seemed to pay attention only to the number of times the information was repeated without considering where the information came from. Why? Perhaps people assume that when one person is cited repeatedly, that person is the one, true expert on that topic. But, in a follow-up study, we asked other participants exactly this question: all else equal, would you rather hear from five independent sources or one single source? Unsurprisingly, most believed that more sources were better. But here's the shocking part: when those same participants then completed the task described above, they still believed the repeated information that all came from the same source just as much as independently sourced information—even for those who had just said they would prefer multiple independent sources. These results show that as we form opinions, we are influenced by the number of times we hear information repeated. Even when many claims can be traced back to a single source, we do not treat these claims as if we had heard them only once; we act as if multiple people had come to the same conclusion independently. This “illusion of consensus” presumably applies to virtually all the information that we encounter, including debates about major societal issues like gun control, vaccination, and climate change. We need to be aware of how simple biases like these affect our beliefs and behavior so that we can be better community members, make informed voting decisions, and fully participate in debates over the public good. We wanted to finish this article with a fun fact concerning the massive amount of information that people are exposed to each day. So, we asked Google: "How much information do we take in daily?", and we got a lot of answers. Try it for yourself. You'll see source after source that says you consume about 34 gigabytes of information each day. You may not know exactly how much 34 gigabytes is, but it sure sounds like a lot, and several sources told you so. What's the problem? All of these sources circle back to a single primary source. And, despite our best efforts, we weren't able to find an original source that was able to back-up these claims at all. If we weren't careful, it would have been easy to step away believing something that might not be true—and only because that information was repeated several times. So, next time you hear a rumor or watch the news, think about it. Take one moment and ask, simply, "Where is this information coming from?" - By Sami Yousif, Rosie Aboody, and Frank Keil Sami Yousif is a graduate student at Yale University. His research primarily focuses on how we see, make sense of, and navigate the space around us. In his spare time, he also studies how we (metaphorically) navigate a world of overabundant information. Rosie Aboody is a graduate student at Yale University. She studies how we learn from others. Specifically, she’s interested in how children and adults decide what others know, who to learn from, and what to believe. Frank Keil is a professor of psychology at Yale University and the director of the Cognition and Development lab. At the most general level, he is interested in how we come to make sense of the world around us. This post is previously published on the Society of Personality and Social Psychology; Character and Context Blog For Further Reading: Yousif, S. R., Aboody, R., & Keil, F. C. (2019). The illusion of consensus: a failure to distinguish between true and false consensus. Psychological Science, 30, 1195-1204. When you think about what you might learn by completing a PhD, it’s natural that you might focus on the most obvious outcome: expertise in the research topic. Sure, it is true that by the end of your PhD you will know a lot about your chosen topic but what you might not realise is that, along the way, you will also learn other important skills that are completely unrelated to the research topic. Here are the top 3 things that I learnt: 1. Dealing with uncertainty By the very nature of a research PhD, you aren’t sure what the outcome of your research is going to be when you start. The reason why you are doing the research in the first place is to answer an as yet unanswered question! Importantly however, you will realise that while sometimes your studies work out and sometimes they don’t, your PhD rolls on regardless of the outcome. So you learn to deal with the uncertainty and push on. This is a great skill to have when you are starting a new job or a new project. During such times you will inevitably feel unsure or uncertain but knowing that, with hard work and perseverance, the moment will pass is reassuring. 2. Dealing with the imposter syndrome I originally titled this sub-heading ‘Overcoming the imposter syndrome’ but that would not be true. By the end of my PhD I had not overcome the imposter syndrome but I did get to a place where it would not stop me from doing what needed to be done. What I learnt was that EVERYONE suffers from imposter syndrome, from students through to professors. Those that succeed in their careers have simply learnt how to ‘handle it’. Some tips that have helped me to ‘handle it’ are:

3. Time and project management skills For 99% of people, completing a PhD will be the longest, hardest and most complex project that they have undertaken in their career to date. So don’t underestimate the skills that you gain in terms of time and project management. You might have to learn some of those lessons the hard-way but by the end of your PhD you will have a greater understanding of what it takes to manage your time and what project management systems (software, lists, charts etc) work for you. In the end, like an increasing number of PhD graduates, I now have a job outside of academia unrelated to my PhD topic. Not once have I felt that those years were wasted. I use the skills that I learnt and draw almost daily from the countless amazing people that I met throughout my PhD. And mostly I am grateful for the opportunities that completing a PhD afforded me, beyond my topic expertise. And if you ever need to talk to an expert in community engagement with stormwater imagery – you know where to find me ;-) - By Tracy Schultz The grass is not always greener in my neighbor’s garden… At least, that’s what people seem to think. In fact, when asked about others’ opinions toward sexual minorities’ issues, people tend to overestimate the level of intolerance in their society regardless of their personal views. In Switzerland, for example, residents thought that most other residents, including their neighbors, were intolerant toward same-sex marriage and same-sex parenting. Yet, this was not the case; Swiss residents were actually much more tolerant than what people thought (Eisner, Spini, & Sommet, 2019; Eisner, Turner-Zwinkels, Hässler, & Spini, 2019). You wouldn’t be surprised to hear that this perception of intolerance might impact on sexual and gender minorities’ well-being. To illustrate, perceptions of an intolerant climate toward sexual and gender minorities might raise expectations of rejection and, therefore, lead to concealment of one’s sexual orientation/gender identity and internalization of stigma. Moreover, perceptions of an intolerant climate might also affect social change processes themselves. Indeed, if you perceive that others in your society are intolerant of sexual and gender minorities, you might be discouraged from engaging in support for social change: “People aren’t ready for social change, thus, a social movement won’t be successful. So, let’s wait a little bit longer before pushing toward greater equality for sexual and gender minorities”. On the other hand, the intolerance you perceive might make you angry. This may lead you to believe that social change cannot be achieved without action: “This situation makes me so angry, we need to engage now because the situation is not getting better”. Hence, perceptions of intolerance could discourage or encourage support for social change. What did we do? While perceived climate might be relevant in all social movements, perception of others’ intolerance might particularly impact countries in which there are striking legal disparities. In Switzerland (and this might surprise you) sexual and gender minorities still suffer from many legal discriminations, such as being denied the right to marry and adopt. The legal discrimination goes so far that a single person can adopt a child, but as soon as you are in a registered same-sex partnership, you are not allowed to adopt children anymore. Importantly, while both sexual and gender minorities face many legal inequalities, the legal challenges of both groups are different. The present research was tailored to sexual minorities (e.g. homo-, bi-, pansexual people) since up-coming public voting regarding same-sex marriage affects sexual minorities. We tested the basic question of whether perceiving intolerant others discourages and/or encourages support for social change toward greater equality for sexual minorities in Switzerland. We gathered answers in our online questionnaire from sexual minorities (1220 participants) and cis-heterosexuals [1] (239 participants). What did we find? Perceiving others to be intolerant actually has a paradoxical impact on one’s support for social change:

What does this mean? Our research shows that the following detrimental effects of perception of an intolerant climate on support for social change must be key considerations when mobilizing for social change:

- Léïla Eisner & Tabea Hässler

This blog post is based on: Eisner, L., Spini, D., & Sommet, N., (2019). A Contingent Perspective on Pluralistic Ignorance: When the Attitude Object Matters. International Journal of Public Opinion Research. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edz004 Eisner, L., Turner-Zwinkels, F., Hässler, T., & Spini, D., (2019). Pluralistic Ignorance of Societal Norms about Sexual Minorities. Manuscript under review; Eisner, L., Hässler, T., & Settersten, R. (2019). It’s time, act up for equality: Perceived societal norms and support for social change in the sexual minority context. Manuscript in preparation. [1] The term cis-heterosexuals denotes heterosexual individuals whose gender identity corresponds to their assigned sex. Lean in! Take a seat at the table! Show the will to lead! Women are often told that this is the way to get ahead in the workplace and overcome inequality. So, what opportunities are available for women in academia to lean in? We know that, within academia, women are more likely to be asked, and to take on, so-called service roles. These roles might indeed lead to a seat at the table, but research shows that these roles are often under-valued when it comes to career progression. But if you’re asked to take on a leadership role – or if, like me, you actually like academic leadership – how can you ensure that ‘leaning in’ enhances your career? Here are six ‘top tips’ gleaned from my experiences: 1. Be selective In academia, women are more likely to be asked to take on more ‘nurturing’ roles. This often reflects commonly held stereotypes about what both women and men are ‘good at’. But I’ve found that academic leadership works best if you’re genuinely passionate about your role. When I took on the role of Director of Education in 2012, I truly believed that we could do things better in the department and wanted to focus my energies to improve the student experience. For other people (and I’m going to name drop some of my amazing colleagues here) their passion might be promoting increased access to higher education (Lisa Leaver – also speaking in Soapbox Science Exeter 2019) or promoting women in science (Safi Darden – one of the amazing Soapbox Science organisers). 2. Negotiate If you’re asked to take on a leadership role, don’t be afraid to negotiate (especially if it’s clear that none of your colleagues want the role!). Many women don’t negotiate because they recognise, consciously or subconsciously, that negotiating is fraught for women in ways that it is not for men. Indeed, research suggests that women are equally likely to negotiate than men (e.g., asking for a raise), but are much less likely to be successful. Sadly, you are unlikely to get a pay raise for taking on an academic leadership role, but you might be able to negotiate for other benefits, such as a period of study leave at the end of your tenure or additional research support or access to training opportunities (e.g., the Aurora program). 3. Delegate Full disclosure here: I am very bad at delegating…but this was one of the key lessons I took from my first leadership role as Director of Education into my second role as Director of Research. There are many reasons why it’s important to delegate: if you don’t, and you try to do everything yourself, you will burn out! But delegation is also about communicating trust and confidence in the people around you – that you believe that they will do a good job (even if it’s not exactly the way you would do it!). Delegation is about empowering others. So, if people offer help – take it! 4. Say no Full disclosure again: I find it very hard to say no…but we (women) need to do it more often. Throughout my career, I’ve often been rewarded for saying ‘yes’ – sometimes this has led to new collaborations or opportunities and people like you more if you do. But as you progress in your career, saying no to some things allows you to say yes to other things. In the last year, I’ve had a ‘no support group’ with some of my friends – each week we share the tasks we’ve said no to, and we congratulate each other on how we’ve protected our time or saved ourselves from a future obligation. 5. But it is OK to say yes As I’ve said, I find it hard to say no, and often end up saying yes. I confessed this to my ‘support group’ and my very wise friend noted four considerations when deciding whether to say yes. First, could the person do it themselves, even if it’s inconvenient or difficult? Second, can you do it without neglecting your own responsibilities, relationships, or self-care? Third, are you happy to do it or will you resent it later? Finally, will it help them to be independent or will it make them more dependent in the future? By thinking about these questions, you might find yourself saying yes to optional tasks, but you will be more mindful about it. 6. Do it well To return to the idea of ‘leaning in’, it’s not enough to take your seat and keep it warm. For academic leadership to enhance your career, you need to get stuff done and make a difference. When you take on a role, take time to think about how you can make your workplace a better place (however you define better) and how you can achieve it. Make sure that your achievements are visible (to help your career) and ensure that you’ve put structures in place that will make any impact sustainable after you leave the role (see #3). Being an academic leader is one of the most exciting and rewarding parts of my job – every day I feel like I’m making an important contribution to my discipline and I get to support my colleagues, especially early career researchers, to achieve their goals. - Guest post by Joanne Smith (Twitter: @jorosmith)

Joanne Smith is an Associate Professor and Director of Research in the School of Psychology at the University of Exeter. She was also Director of Education from 2012-2014. Joanne studies how the groups that we belong to influence our behaviour and how we can harness insights from social psychology to promote behaviour change. She studies social influence and behaviour change across multiple domains, with a focus on health and sustainable behaviour. Joanne will take part in our Soapbox Science Exeter event, on Saturday 29th July 2019. There she will talk about “With friends like these: How groups influence our behaviour for better…or for worse”. This blog post is previously published on Soapbox Science When groups of people actively help each other (“intergroup prosociality”), what is the driving force? Are all types of helping motivated by the same psychological processes? In a recent paper, we delved into these questions by reviewing what we know of intergroup prosociality from a psychological perspective Benevolent support or political activism? When we think of all the ways that people show concern for others, we may start listing things like donating to international aid campaigns, listening to stories of suffering with empathy, or marching in a rally to bring about more equitable conditions for a disadvantaged group. Do all of these stem from the same values or beliefs? In this paper, we argue that there are two different ways people engage in inter-group prosociality - benevolence and activism. Benevolence aims to compassionately alleviate the suffering of others. Acts such as charitable giving, or listening empathetically to the painful experiences of others would fall under this category. Activism aims to create change in social and political systems to bring about greater equality. The focus here is the recognition of harm and disadvantage brought on by systems, and working to challenge these systems through group-level action. Many types of collective action fall into this category. This distinction forms the basis through which we view how groups of people engage in various forms of prosociality. But of course, there are complexities! For example, how should charitable giving be categorised? – Is it benevolence, activism, or both? While charitable giving has been mostly studied in a way that lends itself to the benevolence definition we provided, charitable giving can also be motivated by motives to bring about equality, and giving to charities that are most likely to bring about structural social change. This argument complicates our traditional view of charitable giving and presents evidence that charitable giving can be both! And what about intergroup contact – What does it have to do with intergroup prosociality? Intergroup contact refers to exchanges between individuals of two different groups, and when it is positive, it has been shown to reduce the prejudice of advantaged group members towards stigmatized groups. Positive contact could be argued to be associated with benevolence rather than activism. Yet recent research on contact has shown that positive contact between advantaged and disadvantaged groups, while reducing the prejudice of advantaged group members, also weakens the disadvantaged groups’ motivations to engage in activism on their own behalf. In this way, contact can reinforce the inequality between advantaged and disadvantaged groups. So what is the solution? Is the choice between mobilizing the disadvantaged group or reducing the prejudice of advantaged groups? Not necessarily. Recent work shows that when the advantaged group acknowledges the inequality and explicitly supports social change, it promotes both groups’ activism as well as positive attitudes. This type of contact has been termed supportive contact. Finally, is there a distinction between allyship and solidarity? Although the terms are often used interchangeably, we make the argument that it might be useful to think about how the motives for the two are different. In Allyship, the advantaged group is helping the disadvantaged group because of some benefit to themselves, for example for their own political aims, to conform to their own group’s norms, or to act out their values. However, when one group stands in solidarity with another, it can mean that they feel identified with that group. In other words, allies might feel part of a larger group together with the people they are helping (“we are all Australian”, or “we all want gender equality”). If there are two different types of motives, we can look at which ones are more common, last longer, or are more likely to spur real change. For example, maybe allyship motives are more common, but solidarity motives are stronger and more likely to lead to social transformation! The paper also highlights an exciting and emerging trend in solidarity research to move beyond advantaged and disadvantaged group dynamics, and look at how disadvantaged groups engage in solidarity with each other. onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/spc3.12436

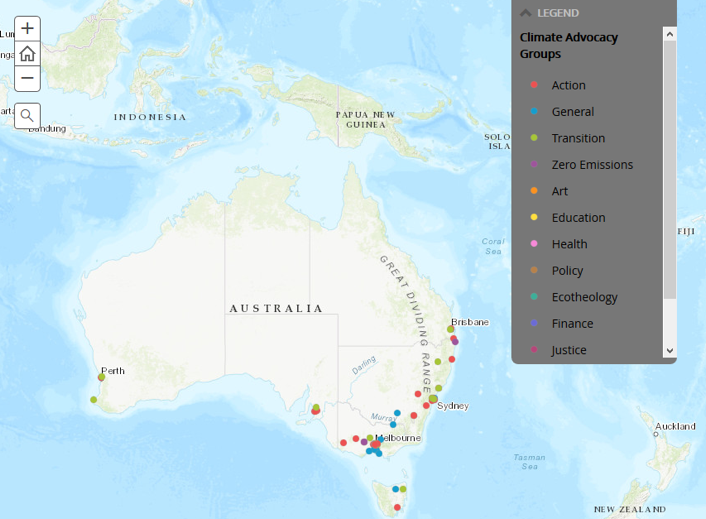

For those interested in intergroup relations, this paper details the many ways groups engage in prosociality with one and other. It provides a detailed review of the research and a helpful way to understand and distinguish between benevolence and activism when we consider the ways groups engage in helping with each other. We look forward to any feedback! - Zahra Mirnajafi This blog post is based on: Louis, W. R., Thomas, E., Chapman, C. M., Achia, T., Wibisoni, S., Mirnajafi, Z., & Droogendyk, L. (2019). "Emerging research on intergroup prosociality: Group members' charitable giving, positive contact, allyship, and solidarity with others." Social and Personality Psychology Compass 13(3): e12436. Activists are time and resource poor. They create social change by making quick decisions in stressful conditions, and often suffer disproportionately for their efforts. Given the urgency of our social and environmental challenges, linking activists with the latest research on topics ranging from how to engage in effective communication, to tactical decision making, to activist self-care, is more important than ever. Yet this research is mostly hidden behind paywalls or it is time consuming to acquire and apply. Thankfully, digital technologies offer a new opportunity to bridge the activist-researcher. Throughout my time here in the Social Change Lab, I’ve experimented with piloting effective research dissemination. This has lead me to the development of my website, www.earthactivists.com.au. This website began as a communication vehicle for various projects created during my time as a fellow in the University of Queensland Digital Research Fellowship program. The website is based on an initial dataset of 497 Australian environmental groups and 901 environmental campaigns. Mapped through the Esri ArcGIS online platform, the data and associated map will allow activists to easily view campaigns across all environmental issues, compare the data available on them, and track the campaign outcomes over time. Combined with archives collected on past environmental campaigns, one goal of the project is to create an open and accessible ‘treasure chest’ of information on Australia’s rich and diverse environmental movement. Open data can inform what type of activism is more likely to succeed; for example, data collected on over 100 years of protests demonstrates the surprising success rate of non-violent civil resistance as opposed to violence insurgencies. But it can also help enable stronger and more connected activists, reducing the ‘activist fatigue’ experienced through isolation and burnout. To this end, the website hosts stories of women fighting climate change. It also provides insights from experienced environmental campaigners on the highs and lows of activism, how they define success, and how they prioritise and acquire resources for their work. This website, still in its nascent stage, has been informed by international examples of accessible and open data on social change movements. One of the most influential of these examples is the Nonviolent and Violent Campaigns and Outcomes Data Project (NAVCO). This publically available dataset, initiated by Erica Chenoweth, has generated findings of international significance about the importance of non-violence civil resistance, and initiated a new research direction in civil resistance. Another successful open data initiative is that of the Environmental Justice Atlas (ejatlas.com). Centred on a global map of large scale environmental civil resistance campaigns, the project aims to both serve as a tool for informing activism and advocacy, and to foster increased academic research on the topic. Containing information on 2,100 environmental justice case studies, this project has international collaborators both contributing to new case studies and utilising existing studies for their activism and research. These examples demonstrate the new ways digital technology can be used as a bridge between activists and researchers. We have such a rich history of activists and activism around the globe. Collecting and sharing detailed empirical data about social and environmental collective action can help celebrate the work of those who fought for social and environmental justice in the past. But equally importantly, it can help inform how we can generate the urgent action we need to secure our future. In this time of crisis, bringing activists and researchers together is one more important than ever.

- Robyn Gulliver As for many other nations, gender equality in Australia has increased significantly over the last century. By 1923, all women in Australia had the right to vote and stand for parliament. In 1966, women earned the right to continue employment in the public sector after marriage through the removal of the marriage bar (a ruling that barred women from working in many careers after marriage). Female workers in Australia were granted the right to equal pay in 1969, and the 1996 Workplace Relations Act required men and women to receive equal pay for equal work. Whilst inequalities do persist, (e.g., the average Australian woman is earning 85c for every dollar earned by men) there is considerable support for gender equality in the public sphere. However, there is less support for gender equality in private life. An Australian attitudes survey found that 16% of Australians believe men should take control in relationships and be the head of the household, 25% of Australians believe that women prefer men to be in charge of the relationship, and 34% believe it’s natural for a man to want to appear to be in control of his partner in front of his male friends. This issue of gender inequality in the public versus the private sphere has come to the forefront of public discussion recently. The debate around the equal distribution of household chores and caregiving responsibilities is occurring both here and abroad. Heterosexual Australian women average seven hours more housework per week than their male partners. This inequality often starts in childhood, with female children often expected to take on more chores than their male siblings. In adult relationships, habits started in the early stages of the relationship can further increase unequal responsibilities. In this stage, women are more likely to be at home looking after children and cleaning up the house. This dynamic continues even after the female partner returns to work. Early exposure to unequal gender roles and failure to establish equitable dynamics in the early stages of the relationship, can lead to unequal expectations of men and women in romantic relationships. There is light being shed on the double standard regarding expectations of men and women. For example, men are praised for completing chores and looking after their children, when women are simply expected to do these things. As one father noted, the disproportionate praise heaped on men for simply interacting with or looking after their children is not only unfair for women, but condescending to men. Not only do these disparities reinforce unequal gender roles, limiting both men and women, but they may play a role in domestic abuse. When the onus of responsibility for domestic tasks is put onto women, this expectation may be used to justify abusive responses to a failure to maintain standards. For example, if a house is untidy, or a child gets sick or injured, instead of simply acknowledging it as something that happens, it can be viewed as the female partner’s fault, and the female partner’s failure to fulfil their role. Obviously, this is not the case for most relationships, but inequality in the home may be seen by some as legitimising abuse. Unequal home dynamics may also alter the perceptions of work. For example, even if both partners in a heterosexual relationship engage in paid work, emphasis on the female partner’s domestic responsibilities reinforces the idea that the man should be the primary income earner. This also highlights that his career is more important than hers. If the woman’s income or career success exceeds her partner’s, this may result in her partner reinforcing greater inequality in the home in an attempt to retain a feeling of power and control. The recent public discussion of gender equitable distribution of domestic responsibilities raises the question: Why did it take so much longer for equality in the home to become a priority in a nation that prides itself on progressive attitudes regarding gender equality? Perhaps the persistence of gender inequality in the home reflects residual hidden sexism in a culture where the beliefs may not have held pace with changing public norms. - Kiara Minto People often categorise themselves as either politically conservative or liberal. From a social psychological perspective, we often categorise ourselves and compare ourselves with other people. We like to identify who we are, and we do this by distinguishing ourselves from people who belong to other groups. Conservatism and liberalism are opposite ends of the political spectrum; in our perception nowadays, they are worlds apart. However, conservatism and liberalism are relative, and sometimes even cultural. For example, people in new generations often refer to themselves as less conservative and more liberal than older generations. Westerners may refer to themselves as less conservative and more liberal than Easterners. Being conservative in the American context might be considered liberal in the Chinese context. What does it actually mean to be more or less conservative (or liberal)? Is this a difference in cognitive processing? Or a social difference that we have picked up from the society around us? Protecting vs. Providing Motivation Liberals and conservatives differ in what motivates them. Studies with Western samples show that political lefties (liberals or progressives) tend to support policies that provide welfare for societies, whereas political conservatives tend to support policies that aim to protect their country from external harm. Such differences are rooted in the psychological distinction between approach and avoidance motivations. Approach motivation focuses on how we can gain benefits. In general, this motivation seeks to provide well-being by doing good things for ourselves and for others (prosocial behaviours). People with approach motivation are likely to support individual autonomy and social justice. In contrast, avoidance motivation focuses on avoiding harms, and what we should not do. Generally, this motivation seeks to prevent harm and to stop bad behaviours. People with avoidance motivation are likely to be responsive to threat and support social regulations. However, this does not mean that people have only one type of these motivations and not the other. We all have some degree of both motives, and all react to changing situations by adjusting our current motives, but may lean towards one side more overall. More vs. Less Negative Sensitivity Neurologists and psychologists have found a link between people’s political orientation and sensitivity to negative environments. This is known as the negativity bias. A negativity bias means that humans generally tend to pay more attention to negative things. For example, we are generally quicker at recognising angry faces than happy faces. Even though we all have a negativity bias, the degree of negativity bias may be different from person to person. Researchers found that people with more conservative thoughts are more responsive to negative environments than their counterparts. These people are more likely to support policies that minimise harmful incidents (e.g., anti-refugees) or promote their country’s stability (e.g., support military enforcement, support local businesses). In contrast, people with more liberal thoughts are more willing to support policies that provide social welfare (e.g., free access to medical care) or challenge conventional use of power and authority (e.g., rehabilitation of criminals). It is important to note that the negative bias is evolutionarily beneficial, and everyone has it to a certain degree. People who live in more conflict-ridden and more dangerous environments may show more negative biases compared to people who live in a safer environment. In summary, conservatism and liberalism are relative; they represent tendencies of thinking and behaviours, rather than absolute, unchanging characteristics. Those tendencies are rooted in individual psychological and physiological differences. However, they are also shaped by the cultural context and responsive to situational forces as well as group norms and leadership. In diverse environments, both conservatism and liberalism can be beneficial to a country. - Gi Chonu Rioting occurring after a football match is not an uncommon phenomenon. Longstanding hostility amongst football fan groups is a tradition worldwide. Hooliganism is a term that describes violent behaviour perpetrated by football spectators, and we find the phenomenon occurring across the globe. In extreme circumstances, death can be an outcome of such riots. For example, during Honduras’ 1969 World Cup qualification, 2,100 people died. In Indonesia, the country where I lived previously, hostility between two fan groups occurs between groups from two cities that are close together.