|

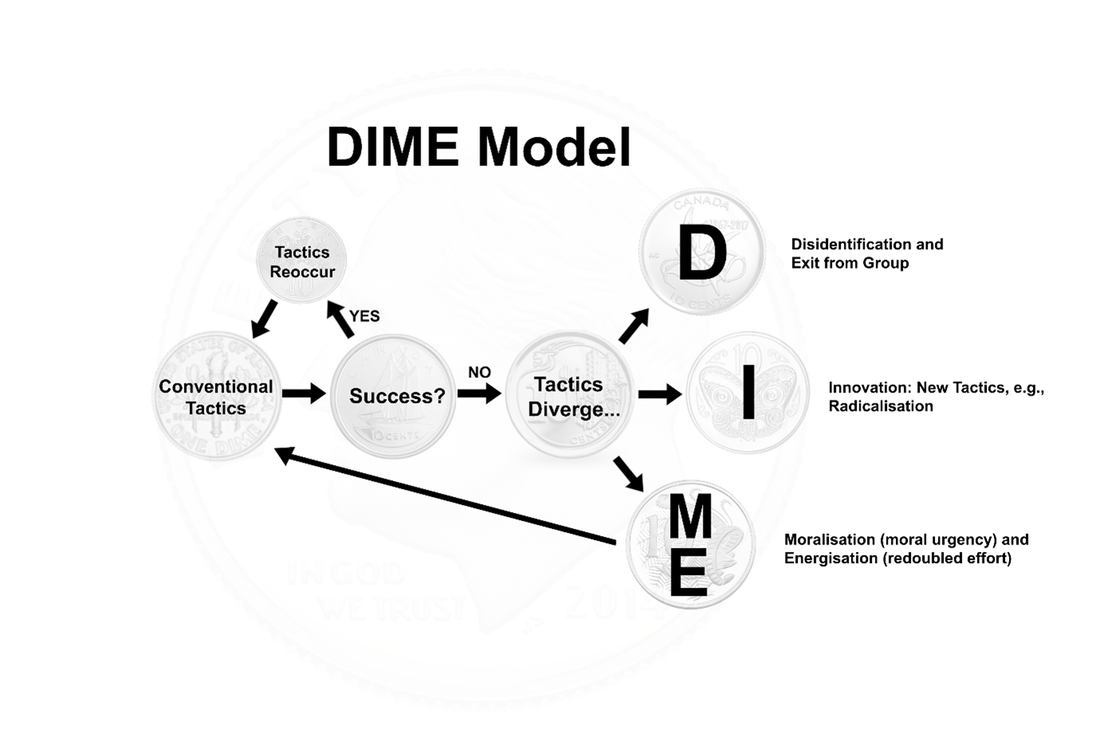

Collective action is a key process through which people try to achieve social change (e.g., School Strike 4 Climate, Black Lives Matter) or to defend the status quo. Members of social movements use a range of conventional tactics (like petitions and rallies) and radical tactics (like blockades and violence) in pursuit of their goals. In this blog post, we’re writing to introduce DIME, which seeks to model activists’ divergence in tactics. The theoretical model is published in an article on “The volatility of collective action: Theoretical analysis and empirical data”, published online here in Advances in Political Psychology. The model is named after a dime, which is a small ten cent coin in some Western currencies. In English the expressions to “stop on a dime” and “turn on a dime” both communicate an abrupt change of direction or speed. With the DIME model (Figure 1; adapted from Louis et al., 2020, p. 60), our goal was to consider the volatility of collective action, and to put forward the idea that failure diversifies social movements because the collective actors diverge onto distinct and mutually contradictory trajectories. Specifically, the DIME model proposes that after success collective actors generally persist in the original tactics. After failure, however, some actors would Disidentify (losing commitment and ultimately leaving a group). Others would seek to Innovate, leading to trajectories away from the failing tactics that could include radicalisation and deradicalisation. And a third group might double down on their pre-existing attitudes and actions, showing Moralisation, greater moral urgency and conviction, and Energisation, a desire to ramp up the pace and intensity of the existing tactics. We think these responses can all co-occur, but since they are to some extent contradictory (particularly disidentification and moralization/energization), the patterns are often masked within any one sample. They can be teased apart using person-centered analyses that look for groups of respondents with different associations among variables. Another approach could be comparing different types of participants (like people who are more and less committed to a cause) where based on past work we would expect that all three of the responses might emerge as distinct. The disidentification trajectory – getting demotivated and dropping out – has been understudied in collective action, and for groups more broadly (but see Blackwood & Louis, 2012; Becker & Tausch, 2014). A major task for leaders and committed activists is to try to reduce the likelihood of others’ disidentification by creating narratives that sustain commitment to the group in the face of failure. Inexperienced activists, those with high expectations of efficacy, and those with lower levels of identification with the cause may all be more likely to follow a disidentification or exit path. Some that drop out, furthermore, may develop hostility towards the cause they left behind. A challenge for the movement therefore is to manage the bitterness and burnout of former members. The moralization/energization path is likely to be the default path for those who were more committed to the group. In the face of obstacles, these group members will ramp up their commitment. But for how long? Attributions regarding the reason for the failure of the initial action are likely to influence the duration of persistence, we suspect: those with beliefs that the movement can grow and would be more effective if it grew may stay committed for a longer time, for example. In contrast, attributions that failures are due to decision-makers’ corruption or opponents’ intractability may lay the groundwork for taking an innovation pathway. A challenge for the leadership and movement is to understand the reasons for the movement failures as they occur, and to communicate accurate and motivating theories of change that sustain mobilisation. Finally, the innovation path as we conceive it may lead from conventional to radical action (radicalisation), or from radical back to conventional (deradicalisation). It may also lead away from political action altogether, towards more internally focused solidarity and support for ingroup members, or towards movements of creative truth-telling and art. There may be individual difference factors that promote this pathway, but it is also a direction where leadership and contestation of the group’s norms would normally take place, as group members dispute whether the innovation is called for and what new forms of action the group should support. The DIME model aims to answer the call to theorise about the volatility of collective action and the dynamic changes that so clearly occur. It also contributes to a growing body of work that is exploring the nature of radicalisation and deradicalisation. We look forward to engaging with other scholars who have a vision of work in this space. - By Professor Winnifred Louis

0 Comments

Polarization in society (division into sharply contrasting groups), can be based on race (e.g., White vs Black), nationality (Australians vs Immigrants), religion (Catholics vs Protestants in Northern Ireland), political ideology (conservatives vs progressives), or even a choice in temporary political contestation (Trump’s supporters vs Hillary’s supporters). How does polarization develop? The trajectory of polarization and conflict does not just happen all of a sudden, but rather goes through stages. Professor Fathali Moghaddam has outlined the three main stages of polarization:

Political elections are ripe grounds for polarization as the competition elections allows for each group to intentionally highlight differences that create the “us” vs “them” mentality. In this process biases such as a tendency to interpret evidence as being more robust if it is in line with prior beliefs are used to gather people’s support. Information access and fake news One process which has the potential to accelerate polarization is the distribution of fake news. During the 2016 US election campaign, hundreds of websites were published in order to strengthen support for one candidate and bring the opposing candidate down. Social media users also propagated a huge number of messages that distorted the facts to voters. However, this is not just a problem in the United States. In Brazil’s 2018 presidential election, a fake voting machine video was retweeted by thousands of social media users after being shared by a right-wing politician. This video was later found to be a hoax. In Indonesia, a politician tweeted about seven containers in one of the ports which were allegedly storing ballot paper pre-marked with votes for one of the candidates. Through his twitter, this politician later asked the police to investigate the information. The tweet raised massive controversy and incited public debates. One group took the information to be fact, while the opposing party reported the politician to the police, accusing him of using technology to spread misinformation. While it is easy to delete a tweet that has been shown to be false, the downstream effect of misinformation is more difficult to fix. It is also challenging to prevent the initial polarization that occurs over a specific issue from developing into more widespread and extreme polarization. As explained by Professor Moghaddam, extreme polarization develops through extreme in-group cohesion. Ingroup cohesion exacerbates polarization as it creates “social bubbles” in which we only hear information that is in line with our group’s beliefs. Within this process, a closed mindset takes place within a group as a consequence of being bombarded with information with a partisanship bias, or even fake news. As the fake news provides increasing “evidence” of outgroup threat and ingroup superiority, each side becomes more wedded to its own distorted perspectives. Preventing the effect of fake news Stopping fake news from being spread is difficult, and some use it for their own political gain. But, what can people do to protect themselves from the unexpected effects of fake news? We know from studies that education is can be an antidote to fake news. However, we also know that highly educated people can be fooled. For example, some educated people distributed fake news related to politics and religion in the Indonesian elections. Education is extraordinarily important as a buffer against hoaxes and fake news, but the educational process must encourage healthy skepticism for it to be effective. Without active, educated dissent from misinformation campaigns (even when these favour the ingroup), we can expect the cycle of polarization and mutual radicalization to continue in future. - Susilo Wibisono  The Social Change Yearly Lab Photo (Front row - left to right: Gi Chonu, Winnifred Louis, Susilo Wibisono, & Ella Cotterell. Back row – left to right: Vlad Bjorskich (visitor), Carly Roberts, Frederik Wermser (visitor), Cassandra Chapman, Kiara Minto, & Robyn Gulliver. Missing: Robin Banks, Zahra Mirnajafi, Tulsi Achia. I want to start by acknowledging our group’s successes: For 2018, I have to salute a brilliant group of finishing students - Lucy Mercer-Mapstone, Wei-jie (Kathy) Lin, Tracy Schultz, and Cassandra Chapman, who all submitted their PhD theses (whoohoo!). Lucy’s thesis has already been passed (Will Rifkin was the lead advisor), and she was off to the University of Edinburgh on a postdoc from mid-year: well done Lucy! Everyone else is grinding on through the bureaucracy, but this has not stopped them re career launch. Kathy is back with her job as an academic in China (with fresh glory; Shuang Liu was the lead advisor). Tracy Schultz was snapped up by the Queensland Department of the Environment and is making change on the ground (Kelly Fielding was Tracy’s lead advisor). Cassandra Chapman (co-supervised by Barbara Masser) is taking up a postdoc on trust and charities in UQ’s Business school. It’s a pleasure to see everyone doing so well, and we look forward to keeping in touch! As well as from our fearless PhD completers, we saw Ella Cottrell and Carly Roberts both finish honours with flying colours; well done both! Many other students smoothly passed their other milestones (Gi, Zahra, Kiara, Susilo, Robyn), with Hannibal and Robin are coming up soon for their confirmations, and we wish them well. There were also those taking well-deserved leave this year (Gi, with maternity leave, and Tulsi, who is away for health reasons). We welcome these transitions and pauses and look forward to new accomplishments in 2019. In other news: As planned, I revelled all year long in my professorship. It is such a luxury and privilege to be a full professor, and I hope I can continue to use my powers for good in 2019 and beyond.

I also have been revelling since the news broke that we succeeded in getting a new Discovery grant for our team, funded for 2019-2021. I’ll be working with Pascal Molenberghs, Emma Thomas, Monique Crane, Catherine Amiot, and Jean Decety, and we will be looking at the transition to Voluntary Assisted Dying in Victoria and more broadly at norms and well-being for practitioners and the community regarding euthanasia or palliative killing. It is a big beast of a grant and I am very excited to launch into it with our group. Possibly the highlight of the year was when I ran an extraordinarily successful conference in 2018 on Trajectories of Radicalisation and De-radicalisation, with many others – many thanks especially to Susilo Wibisono, Sam Popple, Tarli Young, Jo Brown, and Hannibal Thai. We are moving slowly but inexorably towards having the talks online for speakers, and also slowly and more tentatively towards other publishing projects – We will keep you posted. I also want to pass on a special thank you to our volunteers and visitors for the social change lab in 2018, including Frederik Wermser, Claudia Zuniga, Taciano Milfont, and Kai Sassenberg. I particularly acknowledge the contributions this year of Vladimir Bojarskich (visiting from Groningen to conduct environmental research) to multiple projects and to my own work. Thank you, and congratulations everyone! Other news of 2018 engagement and impact As well as the normal dissemination through keynotes and journal articles (see our publications page), I had great fun this year with engagement. The superb conference on Trajectories of Radicalisation and De-radicalisation was a highlight, but I also want to note the November 2018 Zoos Victoria conference on social science and conservation at which I was lucky enough to give a keynote. My own talk was on avoiding stalemates and polarization, but I feel deeply thrilled about the new work coming through from conservation initiatives that I saw presented there – the scale, the rigorous evaluation, the behavioural measures, the impact! One intervention that we learned about at the conference was delivered to 40,000 school children in Victoria, with 8 focal targets (e.g., around reducing marine plastic pollution), and featured pre, post, and 6-month follow-ups that included counting plastics on beaches and in the bellies of shearwater birds – astonishing! But perhaps most impressive of all to me was the open disclosure of failures and willingness as a community of practice to learn from them. What a great research culture! More broadly I am excited about how the new open science initiatives in 2018 are transforming scholarship, and pleased to report that our lab is now working towards consistency in pre-registration, online data sharing, transparency re analyses, and new commitment to open access. Those of you that follow me from way back know that I tried to create something similar in the 2000s but with little traction. The new wave of #openscience is clearly breaking through to change practices with more success. Paywalls by for-profit journals for tax-payer subsidised research are also ongoing and objectionable, and so it is great to see online repositories like Researchgate make connections to readers more feasible. But I also think that academic publishing is still clearly dominated by pressures for selective reporting and that significant results are much more likely to succeed in running the gauntlet through reviewers and editors. In that context, even more impressive is the leadership by practitioners and scholars who allow others to learn openly from trial and error. This will propel us forward as a field. Well done, Zoos Victoria! Socialchangelab.net in 2018 Within the lab, Zahra Mirnajafi has been carrying the baton passed on by Cassandra Chapman, who started the blog and website last year – thank you to Zahra for all your great work with our in-house writers, our guest bloggers, and the site! I continue to be surprised by the generosity of guest writers, and the take-up of our posts by the community. We are now seeing about 600 readers for each blog post within a week - last year it was 200 within a month! Part of the story has certainly been our lab’s activity on Twitter (and other social media) to promote research, and I hope you will follow @WlouisUQ and @socialchangelab if you are on Twitter yourself. In the meantime, we welcome each fresh bot, family member, academic, or community reader with enthusiasm, and hope to see the trend continue in 2019. What the new year holds: In 2019, for face to face networking, if all goes well, I’ll be at SASP in April in Sydney; the post-conference on contact in Newcastle in April/May; at SPSSI in June; at the APA conference in August; a peace conference in Bogota in July; and ICEP in September. Please email me if you’d like to meet up. I’ll also be travelling extensively from July 2019 to June 2020 due to a sabbatical – I plan visits to Europe (probably in September) and Canada/the US (probably in June and again in November-ish). I’ll be around Australia in Melbourne and Sydney as well as Adelaide for the new grant and for my last one, which is grinding on towards awesome publications – stay tuned. I hope people will contact me if interested in meetings and talks. I also welcome one new student as an associate advisor in 2019 – Mukhamat Surya, who will be working with Adrian Cherney at UQ for a project on de-radicalisation and radicalisation. We also have Claudia Zuniga from the University of Chile as a visitor with us until June, woot! Due to the sabbatical from July, I won’t be taking on new PhD students or honours students this year, but welcome expressions of interest for volunteer RAs and visitors. And of course there are lots of other projects on the go throughout the lab with the bigger team – I can’t wait to see what 2019 brings for us all! - Winnifred Louis Growing up in Divided Societies: Children’s Understanding of Conflict-related Group Symbols10/12/2018 ‘Who am I? Who are you?’ Kids’ understanding of social categories has implications for conflict resolution. How and when children recognize names, symbols and social cues influences how they understand and identify with relevant social groups. How they identify with one group also affects their attitudes and behaviours toward ‘others.’ This effect can be even stronger in settings with a long history of conflict. Northern Ireland, Kosovo and Macedonia, for example are rooted in a history of conflict. The two dominant social groups in each setting have remained notably segregated across neighbourhoods and schools. Although the overt conflict has ended, it has left a lasting effect on post-accord generations. Understanding these effects can help research-based reconciliation and peace-building projects. In the long-term, this can build a healthy and cohesive society. The Helping Kids! project explored how children from five to eleven years old in Northern Ireland, Kosovo and Macedonia perceive prevalent social cues – such as names or icons – associated with conflict-related groups. Across all three settings, children readily recognized cues belonging to conflict-related categories. This recognition increased with age. For example, in Northern Ireland, children identified the poppy as belonging to the Protestant/British community, while the shamrock represented the Catholic/Irish community; in Macedonia, children distinguished between celebratory foods as Macedonian or Albanian; and in Kosovo, children recognized various murals and pop artists as either Albanian or Serbian. The more aware children were of conflict-related group markers, the more they preferred their own groups’ symbols; those who preferring in-group symbols also shared fewer resources (e.g., stickers) with the outgroup. Thus, the way children thought about conflict-related groups had behavioural implications even at early ages. The bright side is that children’s previous experience seems to counteract this pattern. If a child reported more positive experiences with outgroup children, he/she was more likely to share resources with the outgroup.

Previous work in Northern Ireland has identified similar patterns. Children from segregated neighbourhoods in Belfast distributed more resources to ingroup members, especially when they held a strong group identity. Moreover, youth in Belfast who had higher quality and quantity contact with outgroup members had higher peacebuilding attitudes and civic engagement. From this we know that children know about and have preferences for social cues related to conflict-related groups. This knowledge and preference has influences how resources are shared with others, an important first step in peacebuilding. Fostering more positive outgroup attitudes and opportunities for outgroup helping may have promising, long-term implications for more constructive intergroup relations. The Helping Kids! lab is working to apply these findings in other contexts. As such, these findings may have implications for the 350 million children living in conflict-affected areas. - Guest post by Dr. Laura K. Taylor, Dr. Jocelyn Dautel, Risa Rylander MSc, Dr. Ana Tomovska Misoska, and Edona Maloku Berdyna MSc. *This phase of the Helping Kids! project was funded by the School of Psychology Research Incentivisation Scheme (RIS) and the Department for the Economy (DfE) - Global Challenge Research Fund (GCRF) Award [DFEGCRF17-18/Taylor]. * This post is part of a series based on talks given at the Trajectories of Radicalisation and De-radicalisation Conference held at the University of Queensland in 2018.

Recent research suggests that identity fusion, a visceral sense of oneness with the group, is capable for motivating extreme self-sacrifice for others, even willingness to lay down one’s life in order to protect them. The link between fusion and self-sacrifice has been demonstrated in a wide variety of different groups, from rural tribesmen to football hooligans and from religious fundamentalists to revolutionary insurgents. Can identity fusion help to explain the phenomenon of suicide terrorism? In a recent target article due to appear in Behavioural and Brain Sciences, I have argued yes. The article attracted a deluge of commentaries from which twenty-nine were accepted for publication, along with a substantial response from me. The debate is lively but the potential costs for not taking it seriously are high. If I’m right, instead of trying to de-radicalize terrorists we should be trying to de-fuse them. Rather than directly challenging the religious convictions or other kinds of beliefs held by extremists, the idea would be to focus attention instead on their personal experiences, and initiating a process of reframing self-defining memories that give rise to identity fusion in the first place. If such an approach were to work, it would likely need the support of the terrorists’ relational networks, including members of their families, school friends, workmates, and others. Winnifred’s commentary (with Emma Thomas, Craig McGarty, Catherine Amiot, and Fathali Moghaddam*) also makes the argument that people fused with peaceful groups are not at risk of becoming violent extremists, so norm change may be a more relevant path forward for violent groups. I agree that violence condoning norms are likely to be part of the problem, and research we have done on fusion and violence with football hooligans supports this, but changing norms may not be the easiest or most effective starting point in tackling extremism. What we do know from previous research is that fusion is a necessary, even if not a sufficient, condition for certain forms of violent self-sacrifice so de-fusion certainly appears to be one of the options we should be considering in our efforts to tackle the problem. Research on identity fusion has other potentially valuable applications to reduce criminal violence in society. In some cases, there may be benefits in fostering processes of fusion in persons who lack socially desirable group alignments, for example, convicted felons. If a legitimate goal of any criminal justice system is to reform prisoners, to reintegrate them into society as loyal and law-abiding citizens, then one way to do this might be to facilitate fusion with mainstream groups and values. Yet another potential application of fusion theory would be neither to create nor to obstruct group alignments but to harness existing ones, for example, to rebuild societies devastated by conflicts or natural disasters or to redirect the destructive urges of football hooligans into more socially desirable activities. Again, the research to test and translate the theory into application is only beginning to be conducted – and there is plenty of room for more researchers to become involved. - Guest post by Professor Harvey Whitehouse, the University of Oxford. * Louis, W. R., McGarty, C., Thomas, E. F., Amiot, C. E., & Moghaddam, F. M. (in press). The power of norms to sway fused group members. Brain and Behaviour Sciences. Accepted for publication, 11 June 2018. * This post is part of a series based on talks given at the Trajectories of Radicalisation and De-radicalisation Conference held at the University of Queensland in 2018. Young people across the world are growing up in environments marred by violent group-based conflict around religious, racial or political differences. These conflicts can have long-lasting effects, not only among survivors, but also for subsequent generations. These effects, however, need not only be negative; there are also constructive ways that young people react to conflict and its legacy. It is these constructive pathways that we have been researching amongst young people in Northern Ireland in our Altruism Born of Suffering project. What is Altruism Born of Suffering?

Altruism born of suffering (ABS) is a theory that outlines the conditions under which individuals who have experienced risk or harm may be motivated to help others. Key dimensions include whether the harm was suffered individually (e.g., being beaten up) or collectively (e.g., bomb targeted at a community), and whether it was intentional (e.g., hate crime) or not (e.g., natural disaster). It is thought that individuals who experience harm or risk might engage in helping behaviours due to shared past experiences, common victim identity and increased empathy with other sufferers. Whether an individual helps or not might also be influenced by personal and environmental influences such as norms (unwritten rules about how to behave) and past intergroup contact experiences (how often an individual interacts with those from a different group and how positive those interactions are). We believe that understanding the processes underlying these positive pathways following adversity, especially among young people, may be the foundation for more constructive intra- and intergroup experiences that can help to rebuild social relations. Youth as Peacemakers in Northern Ireland As part of our project, we conducted a survey (in Autumn 2016 and then again in Spring 2017) amongst 14-15 year olds living in Northern Ireland (N = 466, evenly split by religion and gender) to examine how ABS might playout in a real-world conflict setting. Participants, born after the 1998 Belfast Agreement, represent a ‘post-accord’ generation. Although not exposed to the height of the ‘Troubles,’ the most recent peak of intergroup violence between Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland, these young people still face ongoing sectarianism and annual spikes in tension. We found that having friends who support youth to have friends from the ‘other’ group is really important in determining how much young people interact across group lines. Furthermore, having intergroup contact is associated with greater support for peacebuilding and being more engaged in society, and with lower participation in sectarian anti-social behaviours. Finally, when youth are exposed to a continued intergroup threat, they are more likely to engage in sectarian antisocial behaviours if families reinforce group distinctions and intergroup bias. Our findings suggest that youth who are living with the legacy of protracted intergroup conflict can be supported to engage in constructive behaviours and that it is vital to recognise the peacebuilding potential of youth. Guest post by Dr. Shelley McKeown Jones, University of Bristol, and Dr. Laura K. Taylor, University of Bristol. |

AuthorsAll researchers in the Social Change Lab contribute to the "Do Good" blog. Click the author's name at the bottom of any post to learn more about their research or get in touch. Categories

All

Archive

July 2024

|

Social Change Lab

Join our mailing list!Click the button below to join our mailing list:

Social Change Lab supports crowdfunding of the research and support for the team! To donate to the lab, please click the button below! (Tax deductible receipts are provided via UQ’s secure donation website.) If you’d like to fund a specific project or student internship, you can also reach out directly!

|

LocationSocial Change Lab

School of Psychology McElwain Building The University of Queensland St Lucia, QLD 4072 Australia |

Check out our Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2017

RSS Feed

RSS Feed