|

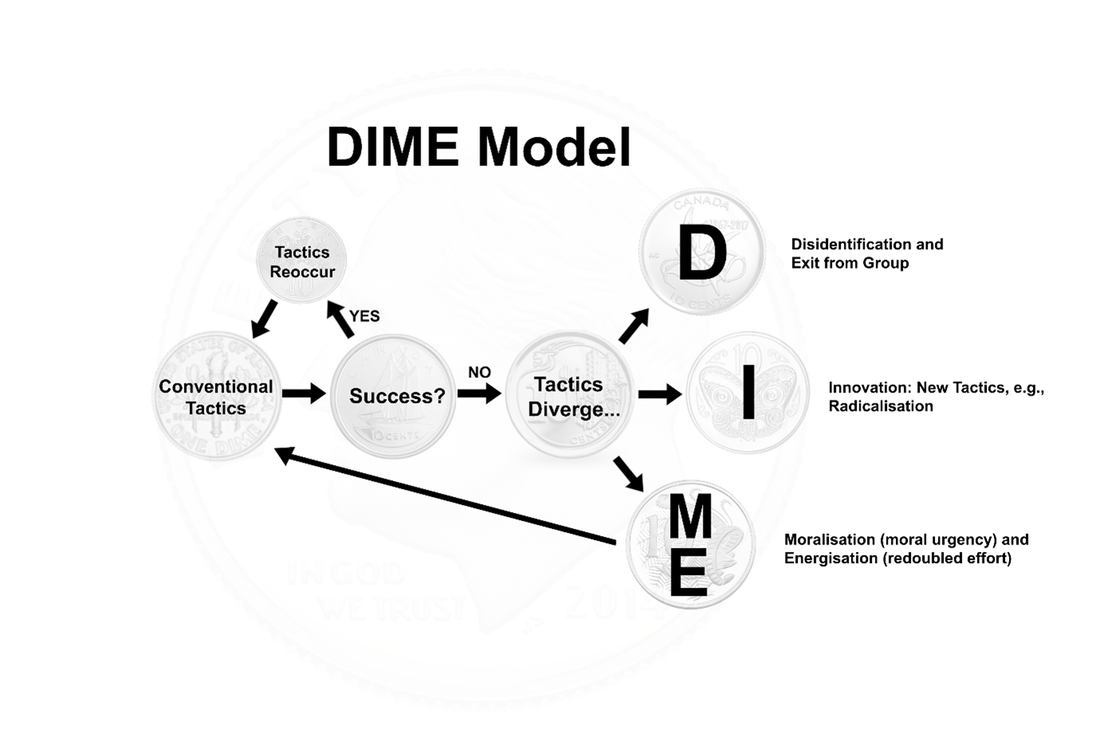

Collective action is a key process through which people try to achieve social change (e.g., School Strike 4 Climate, Black Lives Matter) or to defend the status quo. Members of social movements use a range of conventional tactics (like petitions and rallies) and radical tactics (like blockades and violence) in pursuit of their goals. In this blog post, we’re writing to introduce DIME, which seeks to model activists’ divergence in tactics. The theoretical model is published in an article on “The volatility of collective action: Theoretical analysis and empirical data”, published online here in Advances in Political Psychology. The model is named after a dime, which is a small ten cent coin in some Western currencies. In English the expressions to “stop on a dime” and “turn on a dime” both communicate an abrupt change of direction or speed. With the DIME model (Figure 1; adapted from Louis et al., 2020, p. 60), our goal was to consider the volatility of collective action, and to put forward the idea that failure diversifies social movements because the collective actors diverge onto distinct and mutually contradictory trajectories. Specifically, the DIME model proposes that after success collective actors generally persist in the original tactics. After failure, however, some actors would Disidentify (losing commitment and ultimately leaving a group). Others would seek to Innovate, leading to trajectories away from the failing tactics that could include radicalisation and deradicalisation. And a third group might double down on their pre-existing attitudes and actions, showing Moralisation, greater moral urgency and conviction, and Energisation, a desire to ramp up the pace and intensity of the existing tactics. We think these responses can all co-occur, but since they are to some extent contradictory (particularly disidentification and moralization/energization), the patterns are often masked within any one sample. They can be teased apart using person-centered analyses that look for groups of respondents with different associations among variables. Another approach could be comparing different types of participants (like people who are more and less committed to a cause) where based on past work we would expect that all three of the responses might emerge as distinct. The disidentification trajectory – getting demotivated and dropping out – has been understudied in collective action, and for groups more broadly (but see Blackwood & Louis, 2012; Becker & Tausch, 2014). A major task for leaders and committed activists is to try to reduce the likelihood of others’ disidentification by creating narratives that sustain commitment to the group in the face of failure. Inexperienced activists, those with high expectations of efficacy, and those with lower levels of identification with the cause may all be more likely to follow a disidentification or exit path. Some that drop out, furthermore, may develop hostility towards the cause they left behind. A challenge for the movement therefore is to manage the bitterness and burnout of former members. The moralization/energization path is likely to be the default path for those who were more committed to the group. In the face of obstacles, these group members will ramp up their commitment. But for how long? Attributions regarding the reason for the failure of the initial action are likely to influence the duration of persistence, we suspect: those with beliefs that the movement can grow and would be more effective if it grew may stay committed for a longer time, for example. In contrast, attributions that failures are due to decision-makers’ corruption or opponents’ intractability may lay the groundwork for taking an innovation pathway. A challenge for the leadership and movement is to understand the reasons for the movement failures as they occur, and to communicate accurate and motivating theories of change that sustain mobilisation. Finally, the innovation path as we conceive it may lead from conventional to radical action (radicalisation), or from radical back to conventional (deradicalisation). It may also lead away from political action altogether, towards more internally focused solidarity and support for ingroup members, or towards movements of creative truth-telling and art. There may be individual difference factors that promote this pathway, but it is also a direction where leadership and contestation of the group’s norms would normally take place, as group members dispute whether the innovation is called for and what new forms of action the group should support. The DIME model aims to answer the call to theorise about the volatility of collective action and the dynamic changes that so clearly occur. It also contributes to a growing body of work that is exploring the nature of radicalisation and deradicalisation. We look forward to engaging with other scholars who have a vision of work in this space. - By Professor Winnifred Louis

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorsAll researchers in the Social Change Lab contribute to the "Do Good" blog. Click the author's name at the bottom of any post to learn more about their research or get in touch. Categories

All

Archive

July 2024

|

Social Change Lab

Join our mailing list!Click the button below to join our mailing list:

Social Change Lab supports crowdfunding of the research and support for the team! To donate to the lab, please click the button below! (Tax deductible receipts are provided via UQ’s secure donation website.) If you’d like to fund a specific project or student internship, you can also reach out directly!

|

LocationSocial Change Lab

School of Psychology McElwain Building The University of Queensland St Lucia, QLD 4072 Australia |

Check out our Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2017

RSS Feed

RSS Feed