|

The grass is not always greener in my neighbor’s garden… At least, that’s what people seem to think. In fact, when asked about others’ opinions toward sexual minorities’ issues, people tend to overestimate the level of intolerance in their society regardless of their personal views. In Switzerland, for example, residents thought that most other residents, including their neighbors, were intolerant toward same-sex marriage and same-sex parenting. Yet, this was not the case; Swiss residents were actually much more tolerant than what people thought (Eisner, Spini, & Sommet, 2019; Eisner, Turner-Zwinkels, Hässler, & Spini, 2019). You wouldn’t be surprised to hear that this perception of intolerance might impact on sexual and gender minorities’ well-being. To illustrate, perceptions of an intolerant climate toward sexual and gender minorities might raise expectations of rejection and, therefore, lead to concealment of one’s sexual orientation/gender identity and internalization of stigma. Moreover, perceptions of an intolerant climate might also affect social change processes themselves. Indeed, if you perceive that others in your society are intolerant of sexual and gender minorities, you might be discouraged from engaging in support for social change: “People aren’t ready for social change, thus, a social movement won’t be successful. So, let’s wait a little bit longer before pushing toward greater equality for sexual and gender minorities”. On the other hand, the intolerance you perceive might make you angry. This may lead you to believe that social change cannot be achieved without action: “This situation makes me so angry, we need to engage now because the situation is not getting better”. Hence, perceptions of intolerance could discourage or encourage support for social change. What did we do? While perceived climate might be relevant in all social movements, perception of others’ intolerance might particularly impact countries in which there are striking legal disparities. In Switzerland (and this might surprise you) sexual and gender minorities still suffer from many legal discriminations, such as being denied the right to marry and adopt. The legal discrimination goes so far that a single person can adopt a child, but as soon as you are in a registered same-sex partnership, you are not allowed to adopt children anymore. Importantly, while both sexual and gender minorities face many legal inequalities, the legal challenges of both groups are different. The present research was tailored to sexual minorities (e.g. homo-, bi-, pansexual people) since up-coming public voting regarding same-sex marriage affects sexual minorities. We tested the basic question of whether perceiving intolerant others discourages and/or encourages support for social change toward greater equality for sexual minorities in Switzerland. We gathered answers in our online questionnaire from sexual minorities (1220 participants) and cis-heterosexuals [1] (239 participants). What did we find? Perceiving others to be intolerant actually has a paradoxical impact on one’s support for social change:

What does this mean? Our research shows that the following detrimental effects of perception of an intolerant climate on support for social change must be key considerations when mobilizing for social change:

- Léïla Eisner & Tabea Hässler

This blog post is based on: Eisner, L., Spini, D., & Sommet, N., (2019). A Contingent Perspective on Pluralistic Ignorance: When the Attitude Object Matters. International Journal of Public Opinion Research. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edz004 Eisner, L., Turner-Zwinkels, F., Hässler, T., & Spini, D., (2019). Pluralistic Ignorance of Societal Norms about Sexual Minorities. Manuscript under review; Eisner, L., Hässler, T., & Settersten, R. (2019). It’s time, act up for equality: Perceived societal norms and support for social change in the sexual minority context. Manuscript in preparation. [1] The term cis-heterosexuals denotes heterosexual individuals whose gender identity corresponds to their assigned sex.

0 Comments

Lean in! Take a seat at the table! Show the will to lead! Women are often told that this is the way to get ahead in the workplace and overcome inequality. So, what opportunities are available for women in academia to lean in? We know that, within academia, women are more likely to be asked, and to take on, so-called service roles. These roles might indeed lead to a seat at the table, but research shows that these roles are often under-valued when it comes to career progression. But if you’re asked to take on a leadership role – or if, like me, you actually like academic leadership – how can you ensure that ‘leaning in’ enhances your career? Here are six ‘top tips’ gleaned from my experiences: 1. Be selective In academia, women are more likely to be asked to take on more ‘nurturing’ roles. This often reflects commonly held stereotypes about what both women and men are ‘good at’. But I’ve found that academic leadership works best if you’re genuinely passionate about your role. When I took on the role of Director of Education in 2012, I truly believed that we could do things better in the department and wanted to focus my energies to improve the student experience. For other people (and I’m going to name drop some of my amazing colleagues here) their passion might be promoting increased access to higher education (Lisa Leaver – also speaking in Soapbox Science Exeter 2019) or promoting women in science (Safi Darden – one of the amazing Soapbox Science organisers). 2. Negotiate If you’re asked to take on a leadership role, don’t be afraid to negotiate (especially if it’s clear that none of your colleagues want the role!). Many women don’t negotiate because they recognise, consciously or subconsciously, that negotiating is fraught for women in ways that it is not for men. Indeed, research suggests that women are equally likely to negotiate than men (e.g., asking for a raise), but are much less likely to be successful. Sadly, you are unlikely to get a pay raise for taking on an academic leadership role, but you might be able to negotiate for other benefits, such as a period of study leave at the end of your tenure or additional research support or access to training opportunities (e.g., the Aurora program). 3. Delegate Full disclosure here: I am very bad at delegating…but this was one of the key lessons I took from my first leadership role as Director of Education into my second role as Director of Research. There are many reasons why it’s important to delegate: if you don’t, and you try to do everything yourself, you will burn out! But delegation is also about communicating trust and confidence in the people around you – that you believe that they will do a good job (even if it’s not exactly the way you would do it!). Delegation is about empowering others. So, if people offer help – take it! 4. Say no Full disclosure again: I find it very hard to say no…but we (women) need to do it more often. Throughout my career, I’ve often been rewarded for saying ‘yes’ – sometimes this has led to new collaborations or opportunities and people like you more if you do. But as you progress in your career, saying no to some things allows you to say yes to other things. In the last year, I’ve had a ‘no support group’ with some of my friends – each week we share the tasks we’ve said no to, and we congratulate each other on how we’ve protected our time or saved ourselves from a future obligation. 5. But it is OK to say yes As I’ve said, I find it hard to say no, and often end up saying yes. I confessed this to my ‘support group’ and my very wise friend noted four considerations when deciding whether to say yes. First, could the person do it themselves, even if it’s inconvenient or difficult? Second, can you do it without neglecting your own responsibilities, relationships, or self-care? Third, are you happy to do it or will you resent it later? Finally, will it help them to be independent or will it make them more dependent in the future? By thinking about these questions, you might find yourself saying yes to optional tasks, but you will be more mindful about it. 6. Do it well To return to the idea of ‘leaning in’, it’s not enough to take your seat and keep it warm. For academic leadership to enhance your career, you need to get stuff done and make a difference. When you take on a role, take time to think about how you can make your workplace a better place (however you define better) and how you can achieve it. Make sure that your achievements are visible (to help your career) and ensure that you’ve put structures in place that will make any impact sustainable after you leave the role (see #3). Being an academic leader is one of the most exciting and rewarding parts of my job – every day I feel like I’m making an important contribution to my discipline and I get to support my colleagues, especially early career researchers, to achieve their goals. - Guest post by Joanne Smith (Twitter: @jorosmith)

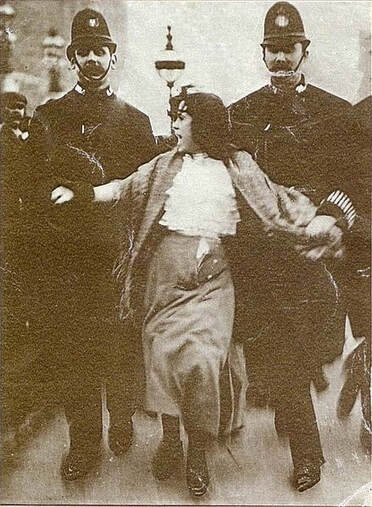

Joanne Smith is an Associate Professor and Director of Research in the School of Psychology at the University of Exeter. She was also Director of Education from 2012-2014. Joanne studies how the groups that we belong to influence our behaviour and how we can harness insights from social psychology to promote behaviour change. She studies social influence and behaviour change across multiple domains, with a focus on health and sustainable behaviour. Joanne will take part in our Soapbox Science Exeter event, on Saturday 29th July 2019. There she will talk about “With friends like these: How groups influence our behaviour for better…or for worse”. This blog post is previously published on Soapbox Science Who Runs The World? …Girls?: Why Female Leaders Struggle to Mobilise Individuals Toward Equality1/7/2019 Have you ever noticed that women are typically the ones spearheading gender equality movements? Think of the suffragettes, the #MeToo, and #TimesUp movements, the March for Women; All fronted by women – but at what cost? Research increasingly shows that relying solely on female leaders is not enough to achieve equality. Perhaps in response to this, there’s been a recent upsurge in male-led initiatives, such as the HeForShe movement, and the Male Champions of Change initiative. Both of these call on men to use their privilege and power to place gender equality on the agenda. These types of initiatives aren’t just companies taking a stab at something new – they’re backed by social psychological research. For example, two recent studies looking at how leader gender affected individuals’ responses to calls for equality found that men and women were more likely to follow a male leader into action (Hardacre & Subasic, 2018; Subasic et al., 2018). Importantly, the only change between the study conditions was the leader’s name and pronouns (e.g., from “Margaret” to “Matthew”). Below, we talk about some of the reasons why female leaders struggle to mobilise people toward equality. “Think manager, think male”: Leadership prototype embodies masculine attributes In our heads, we hold a 'prototype' of particular categories and roles – a fuzzy set of characteristics, attitudes, and behaviours that define certain groups and occupations. For example, if you were to think of a leader, you might think confident, assertive, and even male. Turns out this “think manager, think male” mindset is pervasive. Numerous leadership theories emphasise the desirability of stereotypically masculine traits in leaders. In fact, female leaders are frequently seen as ineffective because individuals’ ideas of effective leadership overlap with agentic male stereotypes (assertive, dominant), rather than communal female stereotypes (warm, nurturing). Even when female leaders do adopt masculine behaviours (such as those seen as typical of leaders), they face backlash because they’re seen as “violating” their traditional caring stereotype. This signifies a Catch-22 situation whereby female leaders are “damned if they do and doomed if they don’t!” Female leaders face accusations of self-interest, while male leaders are seen as having something to lose. It’s also difficult for female leaders of gender equality movements not to appear self-interested and overly invested in their cause (with good reason, given that it IS in their group’s best interests to challenge the status quo!). Essentially, women’s efforts at reducing inequality can be seen as furthering the interests of themselves and their group, and the more women are viewed as trying to benefit their own group, the more cynicism and dismissal they encounter. This can undermine women’s efforts at social change because acts of self-interest are less convincing and influential than acts that seem to oppose one’s best interests. In contrast, because many view gender equality as a zero-sum game, when men challenge gender inequality they’re seen as having something to lose – namely the rights and privilege that accompany their membership of a high-status group. This ultimately affords men greater legitimacy and influence, and therefore greater ability to mobilise followers. Male leaders possess a shared identity with men and women, while female leaders only share an identity with women. Possessing a shared identity with those you are trying to mobilise is at the crux of effective leadership, because those considered “us” are considered more influential than “them”. Herein lies another problem for female leaders. In gender equality contexts, male and female leaders both share a cause with women engaged in gender equality movements whilst men benefit from an additional shared social identity with men.. Meanwhile, no such shared identity yet exists for female leaders looking to mobilise a male audience. Instead, they’re seen as outgroup members by men in terms of their gender group membership, but also in terms of shared cause because gender equality is often seen as a women’s issue and of no benefit to men. Conclusion Paradoxically, by virtue of their gender and the privileges it permits, male leaders seem to have the ability to undertake gender equality leadership roles and mobilise men and women more effectively than female leaders. Research suggests that, among other reasons, this is due to leadership prototypes typically comprising masculine attributes, female leaders’ inability to escape accusations of self-interest, and male leaders’ possession of a shared identity with both male and female followers. It will be interesting to see how long the male ally advantage persists: in the longer term, effective feminist leadership will presumably eliminate the ironic inequality. - Guest post by Stephanie Hardacre (University of Newcastle). |

AuthorsAll researchers in the Social Change Lab contribute to the "Do Good" blog. Click the author's name at the bottom of any post to learn more about their research or get in touch. Categories

All

Archive

July 2024

|

Social Change Lab

Join our mailing list!Click the button below to join our mailing list:

Social Change Lab supports crowdfunding of the research and support for the team! To donate to the lab, please click the button below! (Tax deductible receipts are provided via UQ’s secure donation website.) If you’d like to fund a specific project or student internship, you can also reach out directly!

|

LocationSocial Change Lab

School of Psychology McElwain Building The University of Queensland St Lucia, QLD 4072 Australia |

Check out our Privacy Policy

Copyright © 2017

RSS Feed

RSS Feed