|

Have you ever considered how much, as humans, we are connected to stories? We read stories to children to help them sleep and to ourselves to escape reality. As scientists, we share our research by telling stories that aim to explain what our findings mean and how they apply to life. Our identities are stories, formed by memories that frequently replay and come to describe a sense of ‘me’ – the kindness we've received, the challenges we've faced, the people we love, and the choices we've made. Many of our ideas about love and romance come from stories that are told on the big screen and through social media. And love itself is intertwined with stories: When people enter a romantic relationship, their stories of ‘me’ become stories of ‘us’, based on shared experiences meshed together with another person (Dunlop, 2019). As Toni Morrison (1993) once said, “Narrative is radical, creating us at the very moment it is being created.” Stories create us and our world. Storytelling is also a universal human trait. Evolutionary theorists believe it developed as a way to share information and foster cooperation among early humans, and in turn, promoting group survival (Smith et al. 2017). After all, human history is full of stories, from ancient myths to modern schools of thought. Storytelling is also important in Indigenous cultures. Bessarab and Ng’andu (2010) describe yarning as an Indigenous way of conversing and storytelling, which relies on existing relationships. Yarns are meaningful because they help to create, and are part of, a common social identity: The idea that who we are is based on a sense of us. Because storytelling plays a unique role for Indigenous peoples, it's important to respect cultural differences and not impose a Western story when conducting research in these contexts (Caxaj 2015). This story-based approach is also used in medicine to understand patients' experiences and help them process their health issues – tales of what happened, why, and how can I get better (Fioretti et al. 2016). We can see that stories are everywhere, in our own lives and in the media all around us, from uplifting tales to ones full of conflict. So, why are stories so important to us? Bühler and Dunlop (2019) suggest that stories help us make sense of the world, by providing logic and meaning by combining our past, present, and future. The tales we know help us navigate our own tales of woe. This helps us adapt and change over time. As we’ve seen, stories also shape our identity and group memberships, helping us feel unique and connected. It’s always a special moment when we share a story with the people we care about. If asked, "Who are you?" you might describe your roles and social groups, like family, friends, and work. Being a part of a group has always made us feel as though we are more – a part of something bigger than just a simple, lonely ‘me’. Ultimately, stories help us learn, teach, organise our lives, understand events, and define who we are. They are embedded in every aspect of the human experience: history, culture, language, and identity. We are truly enamoured of stories. Further Reading:

Bessarab, D., & Ng'andu, B. (2010). Yarning about yarning as a legitimate method in Indigenous research. International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies, 3(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcis.v3i1.57 Bühler, J. L., & Dunlop, W. L. (2019). The narrative identity approach and romantic relationships. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 13(4), n/a–n/a. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12447 Caxaj, C. S. (2015). Indigenous Storytelling and Participatory Action Research: Allies Toward Decolonization? Reflections From the Peoples’ International Health Tribunal. Global Qualitative Nursing Research, 2, 2333393615580764–2333393615580764. https://doi.org/10.1177/2333393615580764 Dunlop, W. L. (2019). Love as story, love as storytelling. Personal Relationships, 26(1), 114–136. https://doi.org/10.1111/pere.12271 Fioretti, C., Mazzocco, K., Riva, S., Oliveri, S., Masiero, M., & Pravettoni, G. (2016). Research studies on patients' illness experience using the Narrative Medicine approach: a systematic review. BMJ Open, 6(7), e011220–e011220. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011220 Morrison, T. (1993). Nobel Lecture. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Prize Outreach AB 2024. Accessed Tue. 9 Jul 2024. https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/literature/1993/morrison/lecture/ Smith, D., Schlaepfer, P., Major, K., Dyble, M., Page, A. E., Thompson, J., Chaudhary, N., Salali, G. D., Mace, R., Astete, L., Ngales, M., Vinicius, L., & Migliano, A. B. (2017). Cooperation and the evolution of hunter-gatherer storytelling. Nature Communications, 8(1), 1853–1859. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-02036-8

0 Comments

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has fuelled debate about who is ‘European’. Yet, European identity is an elusive construct. A European identity can offer a sense of belonging to a group larger than the nation, prompting solidarity with a larger collection of people. Youth are more likely to identify as European than their older counterparts; moreover, childhood and adolescence are crucial periods for identity development. Here, we synthesise research on the development of European identity across childhood, adolescence and young adulthood.

We conducted a Rapid Evidence Assessment of European identity in 4-25 year olds, to understand (1) how to measure European identity, and what (2) predictors and (3) outcomes are linked with youth’s European identity. The REA included 11 papers from disciplines such as psychology, education and sociology. Across the studies, five themes summarised how European identity is defined and measured in young people (Figure 1). The Complexity of European identity is reflected in the lack of a consistent tool to measure European identity, and permeates the other themes. European identity is also Ascriptive, as youth choose to identify as such, in search of the sense of Belonging that it may bring. European identity is closely related to the EU motto, United in Diversity, as we see both Similarity – such as a shared culture, history, desires and political identity, and Difference – as national subgroups under the ‘European’ umbrella have different historical, cultural and linguistic roots; there is variation in who identifies as European. But, how is a European identity fostered? What implications does a European identity bring for those youth who hold it dear? School-based interventions and tailored curricula can contribute to stronger European identification among youth, though effects vary based on group membership and status. Artistic programmes give insight into European identity construction among younger children. Knowledge about Europe and the EU give rise to stronger European identification, though political trust and the benefits of EU membership are stronger influences. Cross-border experiences through travel and friendships, and higher socio-economic status contribute to stronger identification. In terms of the implications of European identity in youth, two main benefits have been identified: more positive intergroup attitudes and political participation. There is a small but growing body of research on European identity among young people. Developing a measurement tool which taps into the complexities of the development of European identity is a fundamental next step in this research. Furthermore, only one study focused on youth under age 12, pointing to the need to study childhood. Given the promising findings of school-based interventions, and the effect of such a (potentially) unifying identity on social inclusion and political participation, this is an exciting area for future research for the 142 million young people living in Europe today. By Isabelle Nic Craith and Laura K. Taylor  I want to start, as usual, by acknowledging our group’s successes: In 2021, the lab saw Susilo Wibisono, Zahra Mirnajafi, and Kiara Minto awarded their PhDs, whoohoo! Following submission, Zahra continued into a post-doctoral research role working with Jolanda Jetten in Iran; Susilo worked with me on our Voluntary Assisted Dying grant and secured funding for a project on religious and secular environmental collective action in Indonesia (with me and Robyn Gulliver); and Kiara worked on the Voluntary Assisted Dying grant before transitioning in 2022 to a post-doc on Sexual Violence and the Limits of Consent, led by Lisa Featherstone. Well done everyone! I’m looking forward to seeing what you get up to in 2022. Susilo and Kiara were able to graduate in person last year – floppy hats of awesomeness modelled in pix.  Our three 2021 Social Change Lab undergraduate honours students, Mathias Lai Woa, Mary Shaw, and Stuart Wilkinson, also triumphantly submitted their theses and graduated with honours, despite the rockiest year I can recall for ethics and data-collection – and former honours students will know the bar is high on that one. A big ‘Woot!’ all round, and my sincere apologies to the honours students for subjecting them to the new ‘streamlined’ ethics process. I won’t make that mistake again. Below you can see them thinking, thank goodness that’s over! In other good news, Léïla Eisner, who had secured a post doc from the Swiss government to work (online) with me in 2021 on norms and collective action, won a second post-doctoral fellowship from the Swiss government to continue her work in 2022. Congratulations Léïla! In mid-2021, Léïla accepted a Best Dissertation Award from the International Society for Political Psychology for her PhD thesis work, which surely would have helped. Robyn Gulliver, who finished a PhD in 2020 in the lab, completed a post doc on collective action at HKU with Christian Chan and me in 2021, and secured a UQ post doc with Kelly Fielding for 2022; well done Robyn! Robyn also won the distinctive works prize and student prize for the 'Campaign Explorer' citizen science project from the Australian Council for the Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences (the first time someone has won both). Gi Chonu, who graduated in 2020 also, received an award for going above and beyond in her first year of work at the Singapore campus of James Cook Uni, the JCU Quiet Achiever Award – great work Gi! Finally, Cassandra Chapman, who finished in 2019 in the lab, picked up a string of funding – an early career fellowship (DECRA) and two grants (Linkage and Discovery). Congrats Cass! What a way to jumpstart the next phase of your career!

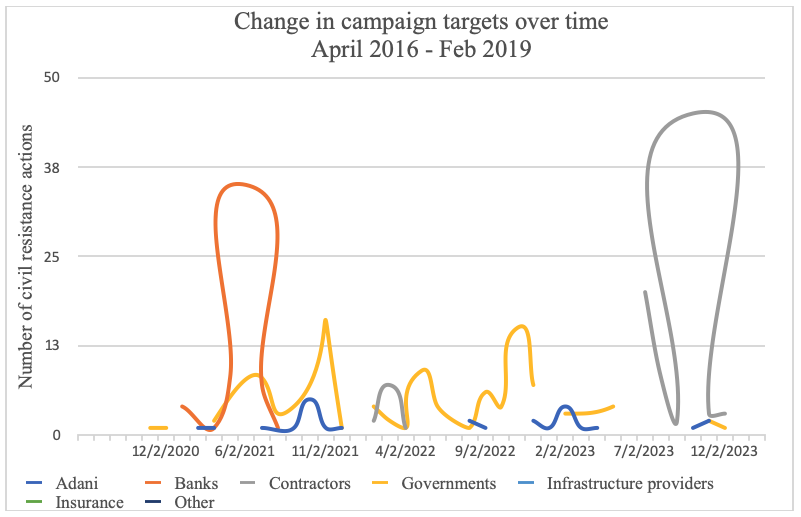

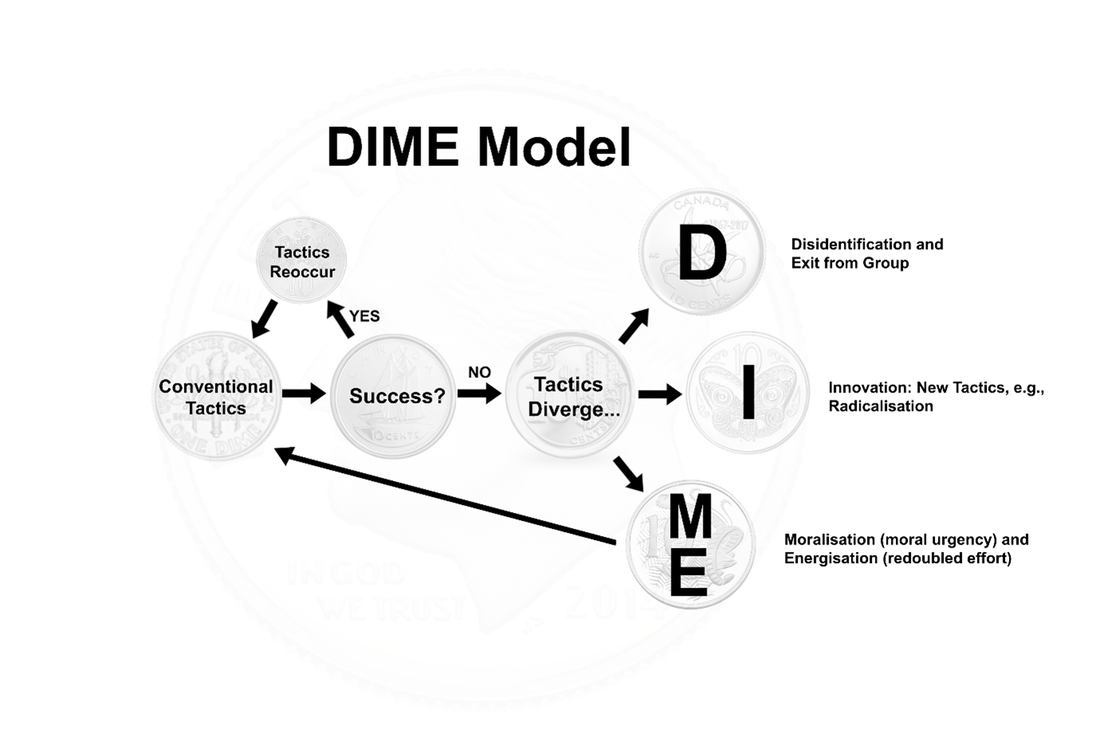

2021 also saw many other students working through their other milestones, including Robin and Hannibal who finished their thesis reviews, and Eunike, Liberty and Tulsi who are moving into their final years after having completed their mid-candidature reviews. Tulsi also started a business, in the middle of the pandemic, which is doing very well – congratulations Tulsi! Our social change lab affiliates, volunteers, and visitors also kept the lab meetings lively in addition to mustering a string of successes of their own. Thank you and congratulations to Alicia Steele, Saleena Ham, Helena Radke, Hema Selvanathan, Jo Brown, Mai Tanjitpiyanond, Mina Fu, Madeleine Hersey, and Zoe Gath. A special shout out to Mai, who won the 2021 Outstanding Postgraduate Research Award from the Society for Australasian Social Psychology (woot!), and to Hema Selvanathan who secured a five year gig at UQ, which is a wonderful step. Well done Hema! It’s also exciting to acknowledge the successes of former students and social change lab visitors and collaborators – Michael Thai and Fiona Barlow won an ARC Discovery in this year's round, and so did our collaborators Annie Pohlman, Emma Thomas, and Vera te Velde. Huzzah! Coming back to our lab visitors and volunteers, I also completed a fun ‘staff-student partnership’ in July 2021 with a team of undergraduate students, who helped to assemble resources for my 4th year course in Applied Social Psychology. Many thanks to this energetic team: Krisya Nor Sabrina Azman, Jason Neame, Megan Kah En Chong, Anindya Permata Putri Tarigan, Kathryn Pearson, Frances Elliott, Samara Phelan, Eugene Cho, Olivia Hannah Mann, and Nanna Thomsen. Tarli Young, Morgana Lizzio-Wilson, Kiara Minto, and Susie Burke also completed guest lectures in PSYC4181. You made the course a lot stronger, and I’m grateful, thank you. In other teaching news, in Semester 1 2021, Jo Brown and I reprised our successful partnership for PSYC3010, and we are also collaborating with another colleague, Janine Lurie, to develop resources for online teaching with JAMOVI. We’ll see how we go in the coming months at taking some steps towards this big transition. In other news looking ahead to 2022, we are excited to welcome Charlie Pittaway to the lab, starting a PhD supervised by Kelly Fielding and myself on youth responses to climate change. Zoe Gath and Madeleine Hersey and Olivia Mann will also rejoin the lab for their 2022 honours year. Welcome! And after this string of congratulations, I want to close by commenting that in 2021, simply keeping your head above water was a huge achievement. To those who spent the year drowning in drama from COVID and elsewhere, I salute you, and I acknowledge your struggle. You are worthy. 😊 Here’s hoping that 2022 is equally and more fun, productive, healthy, happy and social for us and for the group! Other news of 2021 engagement and impact In 2021, we had our normal collective plethora of journal articles (listed below; see also our publications page) and missed out for the most part on conferences, due to the ongoing disruption of COVID (some lab COVID resources listed here). I did participate online in the Indonesia Council Open Conference, as well as in the Social Psychology Association-Indonesian Psychology Association (IPS-HIMPSI) 2021, and some seminars – the one for the AVERT network (Addressing Violent Extremism and Radicalisation to Terrorism) is online here. We also some fun virtual lab meetings – I presented to Immo Fritsche’s group, for example, and our lab hosted three of Martijn van Zomeren’s students and the man himself in a symposium in October. Please reach out if you are interested in this kind of connection, if your lab’s research interests align with ours – it’s easier than ever for us to facilitate this, and great fun and learnings for the students, not to mention staff. I also very much enjoyed being part of the collaborative research project https://psycorona.org/ this year - there are many interesting papers starting to flow from the work, also listed below. It was exciting to finally publish the DIME empirical work in two high impact pieces, a paper led by Morgana Lizzio-Wilson in Psychological Science and our big team’s work in SPPS. I find most of my own papers interesting (*cough*), but I particularly enjoyed the monograph that we published with Cambridge University press (Robyn Gulliver, Susilo Wibisono, Kelly Fielding, and I) on The Psychology of Effective Activism. This piece builds on a lot of past work and has our new theoretical model, ABIASCA, which is about the goals and outcomes of collective action – goals which include raising Awareness, Building sympathy, generating Intentions, turning intentions into Actions, Sustaining movements over time, Coalition-building, and Avoiding counter-mobilisation. I’m happy to share the paper (as well as any others from the lab) if people are interested. Socialchangelab online in 2022 I want to give a big shout out to Kiara Minto, who worked tirelessly in 2020-2021 to solicit, edit, and publish the blog posts at socialchangelab.net, and to encourage creation and updating of our pages. Thank you Kiara for all your great work last year with our inhouse writers, our guest bloggers, and the site! As Kiara has moved on to her new post-doctoral role, I’m looking for energy in this space, so please reach out if you have some. We have some money for this role in 2022, so I’ll be advertising if I don’t get a suitable self-nomination first. We continue to welcome each new reader of the blogs and the lab site with enthusiasm, and if you have ideas for guest blogging, by all means contact me to discuss them. Social Change Lab has received a bequest to facilitate our work in research and research translation (below) so I will hope to see a strong set of writing this year, but always room for more. We also started our Psychology of Change YouTube videos, so fun. A list of the videos is online here and the channel can be accessed here. Season 1 (explainer videos on persuasive conversations) and Season 2 (on collective action) are both already online. I’d like to thank Robyn Gulliver for her vision and persistence with this effort, as well as the wider lab for feedback and suggestions, and James Casey and Lily Kramer who helped out along the way. I also thank the academics who contributed to the published videos, John Drury and Martijn van Zomeren, as well as to thank Dr. Susie Burke, Prof. Daniel Rothbart, and Dr. Maria Fernandez-Jesus, among others, who recorded videos for the lab last year and have been patiently waiting ever since for their publication. Season 3 is bogged down on my laptop due to IT and life drama, but hopefully will see the light of day before too much longer. The lab and I also are still active for work on Twitter, and I hope that you will follow @WlouisUQ and @socialchangelab if you are on Twitter yourself. Our facebook page is now entering its second year: https://www.facebook.com/The-Social-Change-Lab-research-by-Winnifred-Louis-and-team-109966340687649/ . It has been updated in 2021 a patchy and not-that-exciting manner, but we’ll see how it goes in 2022 and beyond. What the new year holds: In 2022, at the moment I have no plans for actual travel, and so it’s all online meetings all the time. However, I do frivol around with zoom a lot and I hope that people will contact me for meetings and talks if interested. I will be participating online at the SPSP pre-conference on extremism in Feb 2022. At UQ, I’ll be teaching third year stats in S1 and Attitudes and Social Cognition (a third year elective) in S2. With colleagues, I also was successful in attracting funding for my work on trajectories of stalemates, gridlock and polarisation as well as unconventional advocates (e.g., conservative environmentalists). The two grants are: Professor Winnifred Louis; Professor Matthew Hornsey; Professor Kelly Fielding; Professor Emma Thomas; Professor Catherine Amiot; Professor Fathali Moghaddam (2022-2024). The psychology of gridlock: Compromise, coalitions, and radicalisation. $407,915.00 This project aims to test an innovative psychological model of collective gridlock. Using interviews, surveys, experiments, small group research, and analysis of social media data, the project aims to examine critical pathways in gridlock psychology, where opponents are locked into mutually suboptimal outcomes, unable to move forward. These pathways include the exit or self-censorship of moderates; normative pressure towards purity and refusal to compromise; tactical choices to avoid coalitions; and radicalisation. The research aims to develop novel interventions to reduce polarisation and radicalisation, and to promote compromises, which together will help society respond more nimbly and effectively to social and environmental challenges. Dr Rebecca Colvin; Professor Winnifred Louis; Professor Kelly Fielding (2022-2024). The effect of unconventional advocates on public support for climate policy. $432,467.00 This project aims to discover whether the presence of unconventional climate advocates in public debate can foster broad-based support for climate policy in Australia. Unconventional advocates include political conservatives, farmers, resource industry workers, and businesspeople. The project expects to generate new knowledge about the role of intersectional social identities in contentious policy debates. Expected outcomes of this project include evidence-based insights on how to reduce social division about climate policy. This should provide significant benefits such as guidance for policy actors for how to overcome social cleavages to implement climate policy, with relevance to other contentious policy domains. Super exciting! I welcome new contacts and collaborators in these areas. Mary Lee bequest As another source of funding, in 2022, we are finally able to acknowledge a very large bequest, more than A$1M, gifted to the Social Change Lab by Mary Lee, who passed away from cancer in 2020. Mary was a psychologist who trained at UQ, and she was struck down in her 40s, with only a short time to grapple with her illness and mortality. She turned to her passion to support peace, democracy, and the environment, and she selected the Social Change Lab as the primary vehicle for that legacy. It is an enormous honour, and of course quite unexpected, to attract such generous philanthropy. I am proud of the work of the team, featured on our website, that caught Mary’s eye when she considered whom to entrust with her legacy. I acknowledge and give thanks for the support of UQ, and Prof. Cindy Gallois in particular, who empowered this connection to occur. After some thought, I have asked UQ to create an endowment fund to receive the support that Mary has bequeathed us. The fund will result in a significant income stream to the lab every year until I retire or leave UQ, which we will be using with enthusiasm to support a wide variety of suitable projects in research, teaching, and research translation. In addition, after my career wraps up, the endowment will be given as a perk to a new Chair (professorial appointment) in the psychology of social change, thereby ensuring that Mary’s vision will continue to support scholarship and application for decades to come. It’s a wonderful satisfaction to know that this great work lies ahead, and I can’t wait to get stuck into it with the team. 2022 is our first year of the Social Change Lab Fund’s operation and as each project is approved, it will be advertised on the socialchangelab.net website and on the present e-list. I look forward to reporting next year on our progress in advancing the psychology of peace, of democracy, and of the sustainable environment, with our own students and with our collaborators and partners. Joining the lab – info for students This year I also am open to new expressions of interest from PhD students for a 2023 start. There is some info on working with me here. For honours students, in 2023 I’ll be teaching a so-called team thesis – a group of 20 students in the ‘work-integrated-placement’ stream. To be honest I’ve little idea what that entails, except that I won’t be supervising any individual honours students for that year. And finally, the list of our recent papers (since 2021) is given below, and if you are interested in a copy of any of these, please do just ask. All the best from our team, Winnifred Louis Publications since 2021 In Press Chapman, C., Lizzio-Wilson, M., Mirnajafi, Z., Masser, B., & Louis, W. R. (in press). Rage donations and demobilization: Understanding the effects of advocacy on collective giving responses. British Journal of Social Psychology. Accepted 18/1/22. Gulliver, R., Fielding, K., & Louis, W. R. (in press). An investigation into factors influencing experienced environmental volunteers’ engagement in leadership and participation behaviors. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. AWR 1/12/21. Gulliver, R., Star, C., Fielding, K., & Louis, W. (in press). A systematic review of the outcomes of sustained environmental collective action. Environmental Science & Policy. AWR 13/1/22. Lizzio-Wilson, M., Wibisono, S., & Louis, W. (in press). Immigrants as Threat and Opportunity: The Australian Experience. In F. Moghaddam & M. Hendricks (Eds.), Contemporary Immigration: Psychological Perspectives to Address Challenges and Inform Solutions. Forthcoming from American Psychological Association. Lizzio-Wilson, M., Mirnajafi, Z., & Louis, W. (in press). Who we are and who we choose to help (or not): An introduction to Social Identity Theory. In M. Bal & M. Yerkes (Eds.), Solidarity and Social Justice in Contemporary Societies: An Interdisciplinary Approach to Understanding Social Inequalities. Accepted 18/7/21. Lizzio-Wilson, M., Amiot, C., Thomas, E., & Louis, W. R. (in press). The psychology of harm-doing. Revised manuscript resubmitted to Wissenschaft und Frieden. Accepted 19/1/22. Himawan, E.M., Pohlman, A., & Louis, W. (in press). Revisiting the May 1998 Riots in Indonesia: Civilians and their untold memories. Journal of Current Southeast Asian Affairs. AWR 20/12/21. Himawan, E.M., Pohlman, A., & Louis, W. (in press). Indonesian civilians’ attributions for anti-Chinese violence during the May 1998 riots in Indonesia. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, in the special issue on ‘Political Psychology of Southeast Asia’, guest edited by Ali Mashuri, Idhamsyah Eka Putra and Cristina Montiel, AWR (!) 8/10/21. Johnson, J., & Gulliver, R. (In press). Public Interest Communication. Press Book. Thomas, E., Duncan, L., McGarty, C., Louis, W., & Smith, L. (in press). MOBILISE: A higher-order integration of collective action to address global challenges. In S. Nicholson & E. Pérez (Eds.), Advances in Political Psychology. Accepted 22/1/22. Thomas, E. F., Louis, W. R., & McGarty, C. (in press). Collective action for social change: Individual, group and contextual factors shaping collective action and its outcomes. In D. Osborne & C. Sibley (Eds.), Cambridge Handbook of Political Psychology. Accepted 1/9/20. Wibisono, S., Louis, W., & Jetten, J. (in press). Willingness to engage in religious collective action: The role of group identification and identity fusion. Studies in Conflict and Terrorism. Accepted 27 May 2021. 2022 Gulliver, R., Wibisono, S., & Louis, W. R. (2022). Rising tides and dirty coal: The environmental movement in Oceania. In M. Grasso & M. Giugni (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Environmental Movements, pp. 123-136. Routledge Ebook ISBN 9780367855680. DOI https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367855680 2021 Dare, M., & Jetten, J. (2021). Preserving prosociality in the face of inequality: A role for multiple group memberships and superordinate group identification. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684302211015303 Durwood, L., Eisner, L., Fladeboe, K. Ji, G., Barney, S., McLaughlin, K.A., Olson, K.R. (2021). Social Support and Internalizing Psychopathology in Transgender Youth. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01391-y . Eisner, L., Hässler, T., Turner-Zwinkels, F., & Settersten, R. (2021). Perceptions of Intolerant Norms Both Facilitate and Inhibit Collective Action Among Sexual Minorities. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684302211024335 Gulliver, R., Ferguson, J. L. (2021). The Advocates: Women Within the Australian Environmental Movement. Melbourne University Press. Gulliver, R.G., Fielding, K. S., & Louis, W. R. (2021). Assessing the mobilization potential of environmental advocacy communication. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 74. DOI: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2021.101563 . Published online February 2021. Gulliver, R.G., Fielding, K. S., & Louis, W. R. (2021). Civil Resistance Against Climate Change. International Centre on Nonviolent Conflict: Washington, DC. Published online September 2021. https://www.nonviolent-conflict.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Civil-Resistance-Against-Climate-Change.pdf Gulliver, R., Wibisono, S., Fielding, K., & Louis, W. R. (2021). The Psychology of Effective Activism. Cambridge University Press, Elements in Applied Social Psychology series. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108975476 . Himawan, E.M., Pohlman, A., & Louis, W. R. (2021). Memahami dinamika psikologis individu yang turut terlibat dalam kerusuhan massa Mei 1998: Sebuah kerangka psikologis [Understanding the psychological dynamics of individuals involved in the May 1998 mass riots: A psychological framework]. Jurnal Psikologi Ulayat: Indonesian Journal of Indigenous Psychology. Published online 21 October 2021. DOI: 10.24854/jpu464 p-ISSN Kadhim, N., Amiot, C., & Louis, W. R. (2021). The buffering role of social norms for unhealthy eating before, during, and after the Christmas holidays: A longitudinal study. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/gdn0000179 Lee, M., Johnson, D., Tanjitpiyanond, M., & Louis, W. R. (2021). It’s habit, not toxicity, driving hours spent in DOTA 2. Entertainment Computing. Published online December 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.entcom.2021.100472 Lizzio-Wilson, M., Thomas, E. F., Louis, W. R., Wilcockson, B., Amiot, C. E., Moghaddam, F. M., McGarty, C. (2021). How collective action failure shapes group heterogeneity and engagement in conventional and radical action over time. Psychological Science. Published online April 2021 https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0956797620970562 Louis, W. R., Lizzio-Wilson, M., Cibich, M., McGarty, C.E., Thomas, E.F., Amiot, C.E., Weber, N., Rhee, J. J., Davies, G., Rach, T., Goh, S., McMaster, Z., Muldoon, O. T., Howe, N. M., & Moghaddam, F. (2021). Failure leads protest movements to support more radical tactics. Social Psychology and Personality Science. Published online 7/9/21. https://doi.org/10.1177/19485506211037296 . Louis, W. R., Cila, J., Townshend, E., Chonu, G.K., & Lalonde, R. N. (2021). Religious norms, norm conflict, and religious identification. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. Published online 24 June 2021. https://doi.org/10.1037/rel0000428 Minto, K., Masser, B. M., & Louis, W. R. (2021). Lay understandings of the structure of Intimate Partner Violence in relationships: An analysis of behavioral clustering patterns. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. Published online 22/1/21. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260520986276 Neville, F., Templeton, A., Smith, J. R., & Louis, W. (2021). Social norms, social identities and the COVID-19 pandemic: Theory and recommendations. Social & Personality Psychology Compass. Accepted 10/3/21. Published online early view https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/spc3.12596 April 2021. Selvanathan, H. P., & Leidner, B. (2021). Normalization of the Alt-Right: How perceived prevalence and acceptability of the Alt-Right is linked to public attitudes. Group Processes & Intergroup Relations, 13684302211017633. https://doi.org/10.1177/13684302211017633 Thai, M., Lizzio-Wilson, M., & Selvanathan, H. P. (2021). Public perceptions of prejudice research: The double-edged sword faced by marginalized group researchers. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 96, 104181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2021.104181 Thomas, E., McGarty, C., Louis, W., Wenzel, M., Bury, S., & Woodyatt, L. (2021). It’s about time? Distinct emotions predict unique trajectories of solidarity-based collective action to support people in developing countries. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 1-12. Published online October 2021, https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672211047083 . Zúñiga, C., Louis, W., Asún, R., Ascencio, C. (2021). The Chilean transition: Achievements, shortcomings and consequences for the current democracy. In L. Taylor & W. Lopez (Eds.), Transitioning to Peace: Contributions of Peace Psychology around the World. Published online, Springer Press. DOI: 10.1007/978-3-030-77688-6_8 . PsyCorona collaboration Mula, S., Di Santo, D., Resta, E., Bakhtiari, F., Baldner, C., Molinario, E., ... & Leander, N. P. (2022). Concern with COVID-19 pandemic threat and attitudes towards immigrants: The mediating effect of the desire for tightness. Current Research in Ecological and Social Psychology, 3, 100028. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666622721000216 Nisa, C. F., Bélanger, J. J., Faller, D. G., Buttrick, N. R., Mierau, J. O., Austin, M. M., ... & Leander, N. P. (2021). Lives versus Livelihoods? Perceived economic risk has a stronger association with support for COVID-19 preventive measures than perceived health risk. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 1-12. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-021-88314-4 Resta, E., Mula, S., Baldner, C., Di Santo, D., Agostini, M., Bélanger, J. J., ... & Leander, N. P. (2021). ‘We are all in the same boat’: How societal discontent affects intention to help during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/casp.2572 Stroebe, W., vanDellen, M. R., Abakoumkin, G., Lemay Jr, E. P., Schiavone, W. M., Agostini, M., ... & Leander, N. P. (2021). Politicization of COVID-19 health-protective behaviors in the United States: Longitudinal and cross-national evidence. PLoS One, 16(10), e0256740. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0256740 This post is a departure from our usual blog format of short pieces about research and practice in our group: it's a personal reflection (from Winnifred Louis) on Donald Taylor as a person, and his scholarship and influence.

I was a masters student with Don starting in 1994, when I wrote a thesis on reactions to gender discrimination at McGill University. I then went on to complete my PhD with him from 1996, looking at reactions to English-French conflict in Quebec. He generously involved me in projects and papers on attitudes to immigrants in South Africa and heritage language retention in Quebec, and we worked together on a paper on responses to 9/11, and then on responses to terrorism. After I graduated, he cheered me on and welcomed my students’ visits. He passed away from cancer last month, in November 2021. I can’t possibly express how much I love the guy and what he meant to me, but here is a short list of some of the key things that come to mind. Autonomous students. Like all Don’s students I worked on projects close to my heart and my interests, I didn’t build an empire for him. He used to laugh at people who would take credit for their students’ work and say, “good supervision is when you set it up for students to steal *your* ideas!”. Students would come in rambling and riffing, and he’d point them to the relevant literatures and send them off to forage, then when they came back, distill their chaotic learnings into hypotheses and a sound research design, and loop them to repeat, as they developed “their” project. Don loved the diverse research that this approach brought to him. And when the PhD students finished, he set them up to develop new collaborations, so they could establish themselves as independent scholars, instead of milking their PhD, not matter how successful it was. “If I couldn’t totally change my research focus every seven years I wouldn’t be here,” he said. Incredible hulk. Don was a guy who was broad-shouldered and beefy, a football and hockey player at the varsity level. His fashion sense was erratic - in our first meetings, I was alarmed by his 70s style, with shirt open to mid chest, and gold chains nestling in his chest hair. I thought this must mean he was terribly sexist – and some of his unsavory comments didn’t help allay that fear, talking about how the girls chased the players on varsity teams, or how he and a friend in grad school had planned to start a university so they could fool around with the undergrad girls. He used to wear an Australian Akubra cowboy hat and oilskins - he liked the look - and signed an email to me in 2020 with a smiling emoji wearing a cowboy hat. Even in our last ftf meeting, when he was in his late 70s, he turned up in his Akubra, and told me with glee how he’d been captured by the cult of cross-fit, referring to himself as a gym-jockey. But what I quickly learned was that for all this flamboyance - he loved attention, he loved sports, he loved physical challenges – Don was very far from the stereotypes of toxic masculinity, insensitive or domineering. Instead, he was a gentle and often a humble person. The more shy and powerless the other person, the more Don was respectful and kind, quick to self-deprecate or joke, hunching down and tilting his head, attentively listening and learning. Support for square pegs. The transition from football scholarship to academic research saw Don scrape over class barriers that were very much alive in the 1950s and 1960s. Maybe that was why he was always ready to support square pegs to work their way into the system. Anyone who battled their way through was liable to find him ready to hold the door open into his lab – female students, or people from minority ethnic groups, at times when that was still unusual at McGill. Refugees from Iran and Rwanda. Myself as a lesbian, at a time when I didn’t know anyone at all, in all of academic psychology, who was openly gay. Quirky characters with narrow focus, and people raging against the system. He savoured the diversity and the joyfulness of people whooshing out the doors of his lab with skills and drive. “You’ve got to launch them!,” he said to me on mentoring grad students. “You don’t just churn them out, you launch them!” Passion for teaching. At the same time Don loved and respected undergraduate teaching. Famously he never missed a class in his 40+ years of undergrad teaching, even the day after a hockey game where he had 20 stitches to his face. “You will influence many more people through your teaching than through your research,” he used to say to me and others. He would teach huge classes of 700, but always remembered to see the students as individual people. He would discard the scheduled lecture content to respond to climactic events, like 9/11. He would talk to students and he would listen to them. I used to fear public speaking tremendously myself, to the point of blushing, trembling, and cracking voice, complete overwhelm. “You feel fear as a teacher when you are thinking about yourself,” he said to me kindly. “Try to think about your students instead - how much you want them to learn what you’re saying. Think about the content, and how much you love the content, and why you care!” Good advice - he was an excellent public speaker. “You’ve got to live for the anecdote!,” he used to say. Don was also a story-teller who would mercilessly blow the time limits of his talks, and of his classes, in order to digress to stories that made people laugh, think and act differently. But he was also someone who, in his everyday life and his career, would turn to go down less travelled paths, stop to hear from unexpected people, and choose something strange and different whenever the choice was offered. “Live for the anecdote!,” he would say. Don’t get stuck in a rut. Don’t pass by the opportunity that won’t come again. Live with panache! Make a difference! Don’s career was impressive in many respects, but perhaps most unusual in showing his long-term commitment to sweeping social change around the world. For five years as a PhD student, I flew up annually on seven-seater planes to Kangiqsujuaq, a tiny village in Arctic Quebec, 100s of kilometers above the treeline. I was part of a 30 year rotating team of students and RAs who learned about the North and contributed to research co-designed with Indigenous Inuit communities on language, identity, and social attitudes. Another time, with Don, I contributed to a special issue in memory of William Robinson, a language scholar who was retiring, and who lamented that at the close of his career he was disappointed that he had not overthrown the class system in the UK. Don and I laughed – but Don applauded that he had never lowered his sights. “They just don’t get it!,” Don used to say irritably, skimming the latest incremental, trivial study, or self-focused theoretical micro-dispute. The world was full of huge problems, with real people struggling - *these* problems needed attention and theorising. The big problems, the big picture – his students were always pushed to consider how our research fit into these categories. Moving beyond the WEIRD context before it was labelled as such, Don introduced me and dozens of other students and collaborators to challenges facing disadvantaged communities, and encouraged us to study them – by going there, by being there, by listening, by working with them, by following their agendas. He supported scholars from the disadvantaged communities and in the global south, and amplified their voices and their theorising. Pragmatism and sober-minded clarity. He was woke before there was wokeness, but at the same time, he would never have presumed that others would feel the same way, or waste time being surprised if others rejected those values. Don was always really clear about the academia that we worked in as not valuing social change or positive benefits to communities, and even being hostile to them. Maybe that’s not true now in some cases – I hope so. But I still teach my students what Don taught me in the 1990s. He said, you need two lines of research: a mainstream one using mainstream methods published in mainstream journals – this will get you your job, tenure and promotion. It will get you grants. The other work, your applied work, you have to be ready to have dismissed. It has to be for the benefit of communities, so it may be slower, or grind to a halt, or blow apart due to politics. Maybe there will be no academic outcomes for years, or at all. Publication may be relegated to journals and conferences that powerful gatekeepers don’t care about at all, or even see as harmful. (In my own career, a former Head of School, which is like a department chair, once remarked, “If you’re going to publish in the Journal of Applied Social Psychology, why publish at all?”) So you have to do both mainstream and applied work, to secure your future, Don would say. You have to publish. But it’s not *just* about job security. Applied work will make you a better theoretician, Don said – more alive to complexity, more aware of received wisdom that’s not actually true. Go outside the box. Look back from the outside. And also: theorising and experiments will strengthen your contribution to application – they will help to untangle causality. And they will credential you to go out to communities and speak to policy makers. Money matters. In the same pragmatic vein, Don was always keenly aware that money matters. He learned from Wally Lambert, a social psychologist at McGill famous for his research and his own memorable stories of cheap-skatedness, to never stay at conference hotels, as being too expensive and a ripoff to the taxpayer. Over the course of his career, Don used to reflect with smugness, he’d directed thousands of dollars from his grants towards research participants and RAs, by staying in shared rooms at hostels when he travelled, or with friends, instead of living it up in luxury. He loved the vibe as well – or at least, male graduate students and RAs that’d shared with him brought back stories of Don sitting around in his boxers playing the guitar, and late nights talking theory and drinking beer. More nefariously, in his later career Don used to sneak into conferences to give his research talks without paying to register for them – something that puzzled and exasperated the conference organising teams, often made up of his former students and friends. “These are ridiculously expensive,” he said at one point when I asked him about it - I guess he decided other student and research expenses were more worthy. It’s a choice he felt was legitimate for him to make, which tells you a lot about him. Bend the rules and make them work for you. Don understood the importance of institutions, and cultivated relationships with policy-makers for immigration, language, and race relations carefully all his career. He also kept a vigilant eye on university politics. But he despised bureaucracy and institutional politicking. So he was always ready to bend the rules. He helped set up courses at McGill for Inuttitut education that effectively became offered in intensives, creating a path that allowed Inuit students to credential themselves as teachers with less difficulty. “What kind of names are these?,” the Dean asked him in bewilderment at one point, peering at the -iaq and -miq graduands – unexpected lists of names ending in q and k. Don used to laugh happily to us as he recalled getting the system to work for the students this way. Look for ways to make what you want to do fit a label the system can live with. Look the authorities in the eye and smile blandly. Hold the door open to let others through. Human at work. All of these things influenced me, and they help me now, and my students too, but the thing that speaks most loudly to my heart now is that long before the term was fashionable, Don was ‘human at work’ – he was authentic and real, and not just defined by his job. He spoke to us about his family, and he asked about mine. He came to my wedding. He played music, and sports, and coached kids’ sports, and took time off for holidays with his wife and kids – and he encouraged us to do the same: take time off for other things. Be real. Have friends and family. “It’s different now,” we used to say to him – we grad students of the 1990s – “it’s too competitive, you’ve got to work all the time and stack up publications, you can’t get by and take weekends off”. “I worry that’s true,” he used to say. But work expands to fill the time you give it. Have the best career you can, within the boundaries you set. Don had a great career. He won national awards for teaching, for research, and for service. He was also deeply loved, as much as anyone else I know or more so. At a symposium we had in honour of Don at the Canadian Psychological Association conference in 2016, people came from all over the world to celebrate his influence and research. I came myself from Australia. He was utterly astonished – he was completely flabbergasted that so many people would go to so much effort to celebrate him and his work. I will close this tribute, as I closed the talk on the day, with these words: Thank you Don! For tremendous support personally & professionally for more than 20 years …For an inspiring vision of a great life filled with joyful curiosity, research, family, sports, music, and activism …For moral indignation always translated with determination and humour into action and alliances, …For boundless scepticism about authorities and bureaucracy, but tremendous faith in teaching, science, and possibilities, … And for highlighting the value of living for the anecdote ! *** Other tributes to Don for those who knew him or are curious: In his own words

Others’ words

What are the key ingredients for successfully developing large-scale cross-disciplinary research proposals? What’s required for a team to successfully work together at the proposal development stage? Here we provide seven lessons based on our experience, divided into:

Team characteristics Lesson 1: Invite a mix of new blood and established experience. It is useful to have team members at various stages of their careers, as well as researchers who have worked together previously and those who have never met before. It can work well to have clusters of researchers who have worked intensively within the cluster, but who are new to each other across clusters. Lesson 2: Foster convergence readiness. Prior experience in cross-disciplinary collaboration can enhance the dynamics of preparing a proposal by combining deep expertise in a discipline with the ability to see how the pieces fit together. Lesson 3: Encourage open questioning. One of the main difficulties with cross-disciplinary collaboration is the longer runway required for takeoff. It takes time to understand other disciplines and develop trusting relationships. This involves listening generously and asking a lot of questions. In addition, specialized disciplinary languages do not translate across all fields, so plain language is needed. To achieve such an environment, we recruit team members with confidence but without big egos. Confidence engenders the security needed to be vulnerable and ask questions, as well as to be comfortable in the unknown. On the other hand, big egos can result in repression of other team members’ perspectives. Structuring the grant proposal writing process Lesson 4: Use a mixture of ways to communicate and work together. Big group conversations are important for coherence, but small working groups are more effective at getting things done. Share the ideas generated in small groups with regular updates and survey questions. In addition, cross-pollinate with boundary-spanners across teams, who may be the leaders of the sub-teams, or individuals liaising across two or more sub-teams. Further, actively weave together thinking and writing. While it can be tempting (and easy) to spend a lot of time talking with each other, writing is a powerful way of communicating and brings much needed clarity to the thinking process. Lesson 5: Shift the academic culture. The collaboration-driven convergence culture stands in sharp contrast to traditional academic culture mired in competition and silos. Researchers need to recognize the interdependence between their success, their colleagues’ success, and the success of the overall research team. Women have an important role to play in shifting the academic culture and fostering collaboration, sharing, and connecting. Lesson 6: Allow plenty of time for team development. Teams need time to form, storm, norm, and finally perform. Take into account the fact that everyone has multiple obligations to juggle, as well as needing downtime at the end of the year and for vacations. Lesson 7: Plan for research implementation and broader impact. Key to research making a difference is long-term partnerships with those who are likely to use the research. For instance, research seeking to contribute to racial equity will only be effective if the researchers already have relevant long-term partnerships, for example with minority-serving institutions. Conclusion This blog post is based on our recent experience developing a proposal for the US National Science Foundation’s Sustainable Regional Systems-Research Networks solicitation. Our five-year $15 million project involved ten academic institutes, with a wide spectrum of disciplines, and 30 other stakeholder groups including state and city governments, non-governmental organizations, and industry partners. What have your experiences been with developing proposals for large-scale cross-disciplinary research projects? What lessons have you have learnt? What roses (strengths), buds (potential) and thorns (challenges) could you share with the community? - By Gemma Jiang, Jin Wen, and Simi Hoque This post was previously published on the Integration and Implementation Insights Blog Biography: Gemma Jiang PhD is the Founding Director of the Organizational Innovation Lab in the Swanson School of Engineering, as well as the founding host of the Pitt u.lab hub and the Adaptive Space at the University of Pittsburgh in the USA. She applies complexity leadership theory, social network analysis, and a suite of facilitation methods to enable transdisciplinary teams to converge upon solutions for challenges of societal importance. Biography: Jin Wen PhD is a Professor in the Department of Civil, Architectural, and Environmental Engineering at Drexel University in Philadelphia, USA. She has about twenty-years of experience in the sustainable building field and has taken several leadership roles in directing large scale collaborative research projects. Biography: Simi Hoque PhD is an associate professor in Architectural Engineering at Drexel University in Philadelphia, USA. Her expertise is in sustainable building design and computational modeling to characterize urban resilience. She is deeply invested in promoting women and girls in engineering. A cross-national study shows that intervention is the norm in public conflicts. KEY POINTS

The recent spate of attacks on Asian Americans in cities around the United States has reinforced the popular belief that bystanders seldom intervene to help strangers, especially in densely populated urban areas. But is that belief correct?