|

From reduced air pollution to cleaner water, the COVID-19 pandemic has provided a vision of hope: evidence that we are capable of rapidly changing our behaviours to build a cleaner, healthier environment. However, what is less clear is whether this vision can be translated into reality. To help investigate this question, the Network of Social Scientists convened an online workshop in late May. The group of around 30 academics and environmental professionals pooled their expertise to explore the effects of the pandemic on the environment. Through investigating the following three questions they identified a range of impacts and barriers to change, as well as techniques for sustaining positive outcomes as the lock downs ease. What have been the environmental impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic? A diverse range of positive and negative environmental effects were highlighted by NESS experts. Many enforced changes from the lock downs led to environmental benefits: more cycling, gardening and engagement in green spaces, a reduction in food waste and greater support for local businesses and food chains were all suggested. In the workplace, a remarkable transition to an online world challenged the dominance of in-person meetings and international travel, both reducing environmental impacts and increasing accessibility and connectivity. Attitudes may have also changed. Trust in experts was enhanced by the centrality of health experts on daily news reports and other media. Some workshop participants believed more positive attitudes towards our ability to create change had emerged, which could flow onto increased mobilization against climate change. Our ability to collectively shoulder immense economic risks to safeguard our health proved that politics can produce results in times of crisis. Some argued that this has shown that the ‘behaviour change barrier’ can be broken. However, as many social scientists noted, behavioral changes are likely to slide as we slowly return to past habits. As well as this concern, NESS experts highlighted the range of negative environmental impacts which were resulting from the pandemic. The drowning out of attention on bushfires and climate change, the continued practice of ‘ghost flights’, a surge in internet and energy use, and the quadrupling of medical waste indicated a high level of doubt about whether any longer term positive environmental benefits will be sustained. What barriers may prevent our ability to sustain positive environmental effects? The UN Secretary General António Guterres hoped that 2020 would be a pivotal year for addressing climate change. Yet despite the horror of the 2019/20 Australian bushfires, media and political attention swiftly re-focused on the pandemic. As the economic and social costs of the pandemic built, NESS experts noted how political barriers resisting change may once again reassert themselves. The renewed focus on development and jobs might serve as a reason or excuse to cut environmental funding, projects and regulations aiming to protect the environment as has happened in previous economic downturns. The prioritization of a gas led recovery indicates limited political support for a fast transition to clean energy. While calls for an Australian ‘green new deal’ are growing, countering the desire to strip back environmental regulation will require a sustained and powerful collective response. As work and holidays returns to pre-pandemic habits, emissions and other negative environmental impacts resulting from commuting and travel may rapidly rise. Turning changed attitudes and behaviours into habits will likely be difficult. A 50% increase in household waste managed by Australian Councils were foreseen by NESS experts. Pivoting back to eco-friendly behaviours such as public transportation use will be likely be discouraged. The surge in use of public green spaces in wealthier nations could be offset by increased deforestation and biodiversity loss in the Global South as newly unemployed migrant workers return to villages to survive. The economic shock of a recession may reduce public support for implementing environmentally beneficial policies. There are myriad localized and personal barriers which may make sustaining environmental positive behaviours much harder to maintain. What insights from social science can help leverage COVID-19 to achieve positive outcomes for the environment? NESS experts suggested three techniques which could be used to overcome the barriers which will drive a return to ‘business as usual’ as our communities emerge from lock down. First, there is evidence from past pandemics that highlighting the positive personal benefits of changed behaviours can spur lasting change. Past pandemics using this frame drove the development of more green spaces, enabling healthier urban environments alongside increased access to nature. Organisations seeking to advocate for permanent post-pandemic changes could seek to frame their messages referencing the personal benefits of clean air and quieter cities, the benefits to health and personal safety, and the financial and time savings to people and firms from reduced travel costs. Second, NESS experts highlighted the value of capitalising on the momentum we have already built in achieving short term changes. Research on dynamic or change norms highlights that the mere knowledge that a growing number of others have been doing a certain behaviour will increase intentions to adopt that behaviour. Third, NESS experts recommended the use of trusted messengers to communicate about environmental change. Celebrate local businesses cementing in more sustainable post-COVID-19 practices. Capitalize on the increased profile of health experts by amplifying messages from groups such as Doctors for the Environment. Work from within organisations to accelerate change and demonstrate the value of a cleaner and healthier world. COVID-19 has powerfully demonstrated the differences in the power of trusted leaders and voices to mobilise, compared to contested or outsider voices. Already the environmental effects of the pandemic have begun to be documented through a range of academic papers and opinion pieces. Whether for good or ill, the pandemic has shown us that we do have the power to change the impact we have on the world. The challenge is now to build a new reality from this brief moment of hope. The summary report from the workshop is available here. - By Dr. Robyn Gulliver This article was originally posted by NESSAUSTRALIA (Network of Environmental Social Scientists).

1 Comment

You did, so you can, and you will – how self-efficacy guides adoption of difficult behaviour.29/6/2020 How can people become more environmentally sustainable? One theory that describes how human behaviour may be influenced is behavioural spillover. Spillover is the notion that doing one behaviour triggers adoption of other behaviours. It’s the idea that engaging in certain behaviours can put you on a ‘virtuous escalator’, where you keep doing more and more. Spillover has grabbed the attention of researchers and policy makers since it offers a cost-efficient, self-sustaining form of behaviour change that when understood properly could be harnessed for fostering the adoption of desirable behaviour. Spillover as a concept is intuitive, since it ‘makes sense’ that one behaviour may influence another. Yet spillover as a phenomenon is far more elusive than intuitive, since there are a growing number of studies with mixed findings about whether or not spillover occurs. The important question within spillover research these days is “how can spillover be encouraged?” We were interested in one particular mechanism: self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is the belief that you are capable enough to be able to do a certain behaviour. We were interested in self-efficacy as a spillover mechanism since it is theorised to have a bi-directional relationship with behaviour. Self-efficacy is influenced by what you have done in the past and self-efficacy influences what you choose to do in the future (known as reciprocal determinism).

Across 2 studies with Australian participants, we explored whether self-efficacy may be a potential mechanism for fostering behavioural spillover. In the first study, information was gathered on participants’ past engagement and intended engagement in 10 water-related behaviours (i.e., behaviours that influence water use, such as water conservation/efficiency and water quality protection behaviours). A pilot study showed that 6 of these behaviours were considered ‘easy’ to do and 4 were considered ‘difficult’ to do. We also measured participants’ sense of self-efficacy towards protecting water quality and conserving water (e.g., I feel confident I can engage in ways to protect water quality). We found that the easy behaviours people have done in the past were related to their sense of self-efficacy, and this greater sense of confidence was associated with increased intentions for more difficult behaviour in the future. These findings were exciting, but two questions remained: 1) is self-efficacy a consistent spillover mechanism? E.g., can we find the effect again? And 2) can this effect lead to actual behaviour? To answers these questions, we used data collected over two occasions with Australian householders that reported whether they were participating in certain water-reducing behaviours and had installed water efficiency devices (e.g., water tank, water efficient washer). Similar to the findings of Study 1, we found that the more water reduction behaviours (i.e., easy behaviours) householders had adopted, the greater their self-efficacy, and the greater their intentions for installing water efficiency devices (i.e., difficult behaviours), in turn, the more of these water efficient devices were actually installed. In lay peoples’ terms, we found that the easy things people had been doing fed into their self-efficacy, which increased their intentions and actual adoption of more difficult behaviour. Ultimately these findings demonstrate support for the idea that self-efficacy may be a mechanism that encourages spillover. These two studies demonstrate associations between past behaviour, self-efficacy, and intended and actual future behaviour, shedding some light on a potential mechanism of spillover. Further testing in real-world settings is needed to understand if self-efficacy can be harnessed and used to inspire adoption of more impactful behaviour. What these findings do suggest is that “from little things, big things grow”! The things we do, even if they are easy and simple, help us to gain the confidence to take on more difficult behaviours in the future. - By Nita Lauren Lauren, N., Fielding, K. S., Smith, L., & Louis, W. R. (2016). You did, so you can and you will: Self-efficacy as a mediator of spillover from easy to more difficult pro-environmental behaviour. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 48, 191-199. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.10.004 The coronavirus restrictions are slowly being eased but the pressures on families at home still probably lead to many tears of frustration. It could be tensions about noise and clutter, keeping up with home schooling and mums and dads torn between parenting and their own work duties. So to make sure our memories of being locked in with our families are as positive as possible, here are some evidence-based tips for calming down, preventing conflict and dealing with any sibling rivalry. Take a deep breath If you feel yourself getting angry at something, breathe in while counting to three. Then breathe out slowly counting to six (or any patterns with a slower out breath). If you do this ten times you should notice yourself becoming calmer. If you’re too agitated to breathe slowly, put your hands on your heart and simply wait until you feel more relaxed. Try counting to ten or 100 before you react. Leave the room and take a break. Plan to deal with the niggle another time. When you’re on break, do something to distract yourself like make a drink, listen to music, look at a beautiful picture or play a video game that is absorbing.

Call a friend or professional helpline to help you get another perspective, especially if you feel scared or hurt.

Different strategies work for different people, so try them all. Encourage your kids to keep trying if they don’t initially succeed. You need to practise any skill to make it feel natural. For younger children, taking a break may be simpler to master. Ease the tension before things blow It’s good to calm down from explosions but it’s even better if you can reduce the build-up in the first place. Take time to share some of the problems upsetting people and see if as family you can negotiate a solution. It’s likely everyone in your family is more tense because of the COVID-19 crisis. Many aspects can’t be easily fixed, like lost work or money stress, but others can, such as creating new routines or sharing space, resources or chores. Work out different ways to get exercise indoors, like games or apps. Plan ahead for the times that need extra care, like when people are tired, or if difficult tasks need finishing. Let others know what to expect. And importantly, lower expectations for everyone. What used to be easy might now be hard, and that’s okay. Control the emotions Help everyone work on managing their emotions. Just because you are experiencing extra distress doesn’t mean you should snap at your loved ones. You need to grow your toolkit of things that make you feel calmer and happier when you’re under pressure.

could be spending time talking about what is going right and what is okay, working with your hands, meditation or prayer, time with your partner, reading or learning something new.

Every day, take time do something from your toolkit to chill out. Talk to each other When the tension is lower, quiet family conversations can help by naming any stresses. Naming things like “this is a stressful time” or “I’m a bit grumpy about work today” helps children process emotions.

t’s important to actively listen to others and celebrate strengths.

Listening and repeating back what others say makes people feel heard, and so does acknowledging shared feelings (“I miss my friends too”). When parents calmly talk about how some things cannot be easily changed, it builds acceptance. Over time, the most powerful thing to prevent explosions is to notice when anger is building so you can deal with it before things escalate. It’s useful to reflect on questions such as “Will this matter in 20 years?” and “Am I taking this too personally?” You can help children by exploring what might really be bothering them. That argument about a toy might be about feeling sad. Try to listen for the deeper message, so they feel understood. Calm that sibling rivalry If sibling rivalry is driving you to distraction, the good news is it does not mean there is something wrong. Low-level sibling bickering is common during times of tension and boredom.

But you should step in when the volume goes up with nasty name-calling or physical contact.

Acknowledge emotions, help the kids express what they feel and encourage empathy. Try to help them decide what’s fair, instead of imposing your view. More serious incidents require you to stop the interaction. If there is harm, separate the kids, care for the hurt child and consider a consequence. Use time-outs to calm things down, not for punishment. But like all conflict, prevention is better than punishment. Does one child need more attention, exercise, stimulation or structure? Do certain toys need to be put away, or shared? Depending on the age of your children, you can help older kids to learn to react gently to provocation. Praise children when they take steps to manage their stress. Remember, these are stressful times for many families around the world. If we can use this time to stay patient, manage tension and act with goodwill towards our loved ones, our families will be better equipped to weather COVID-19, and many other storms that will follow. For more help and information see our website or go to 1800Respect and No To Violence. - By Winnifred Louis, Tori Cooke, Tom Denson, and Peter Streker Tori Cooke is the Head of Workforce Development at No To Violence. Tom Denson is a Professor in Psychology at the University of New South Wales who researches anger regulation and aggressive behaviour. Peter Streker is the Director of Community Stars. This article was written with help from Carmel O'Brien at PsychRespect, and the University of Queensland’s students Ruby Green and Kiara Minto. This post was originally published in The Conversation. Facing COVID-19, communities are trying to strike the balance between locking each other out and keeping each other safe. As government experts and political commentators examine the art of public health messaging for effective behaviour change, lessons could and should be drawn from the most devastating health emergency in recent times: the 2013-2016 Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) epidemic in western Africa. EVD had an incredibly high death rate (50%) and broke out in countries with severely under-resourced healthcare and little public health access. During the EVD epidemic, communities faced similar challenges as with COVID-19, though with even more deadly consequences. Multiagency reports show that early in 2014, EVD public health messaging was understood, but failed to motivate meaningful behavioural change. For example:

Why comprehension may not result in action During an emergency, the individual’s ability to shape what is happening to them is severely reduced. This loss of control leads to a perceived reduction in personal efficacy (an inability to produce desired effects and forestall undesired effects by their actions), leaving individuals with little motivation to act. Social psychological researcher Bandura argues that due to an increasingly interdependent world, people will turn to their communities to accomplish what they cannot individually. Perceived collective efficacy will subsequently determine how confident or discouraged they are to tackle bigger societal problems. In countries with strong emergency infrastructure, however, individuals may turn to state proxies instead of the collective. They may call an ambulance, fire services, or police to assist them in overcoming a challenge they cannot, rather than a neighbour. The proxy replaces the collective. Therefore, it may be argued that collective action during an emergency is made redundant by the state-led initiative. If this were the case with COVID-19, epidemiologists speaking from a government platform via the national broadcaster should command public compliance. Yet, in many cases they do not. Similar patterns were also borne out during the EVD epidemic. Studies confirm that the disconnect between individual comprehension of public health messaging and meaningful behavioural change, was due to a failure of national and international responders to address community practices. That is, national and international leadership overlooked potential collective solutions at the community level, with fatal consequences for those communities. In the latter part of 2014 community health workers and local journalists intervened. To confront EVD, these groups translated public health messaging through a community lens, directly addressing rumours and misinformation. Within six months of community interventions, humanitarian agencies reported significant improvements in prevention measures; over 95% of EVD patients presented to health facilities within 24 hours of experiencing symptoms. Emergency response organisations were able to leverage understanding of local explanatory models, history of previous emergencies, beliefs, practices, and politics through community health workers. Contact tracing and education campaigns were undertaken by local volunteers. Together with religious authorities, new burial practices were enacted. Especially in countries with developed health systems, the COVID-19 response has largely overlooked community responses. The focus on unified top-down policy is important, but the efficacy may be limited as during EVD. Collective efficacy is key to mobilise to save lives and keep each other safe. - By Siobhán McEvoy & Laura K Taylor Laura K. Taylor (PhD) is an Assistant Professor, School of Psychology, University College Dublin (Ireland) and Queen's University Belfast (Northern Ireland). Her research integrates peace studies with developmental and social psychology to study how to promote constructive intergroup relations and peacebuilding among children and youth in divided societies. Siobhan McEvoy is a humanitarian consultant specialising in social mobilisation and community engagement with people displaced due to conflict. Her work has included tackling misinformation during migration of refugees in southern Europe, understanding the use of Rohingya language in responding to health emergencies in refugee camps in Bangladesh and creating strategy for community mobilisation in South Sudan to prevent the spread of Ebola virus disease. Problems within our global and interconnected food systems can result in outbreaks of infectious disease spread by bacteria, viruses, or parasites from non-human animals to humans. This is also known as zoonosis. The swine flu pandemic of 2009, for example, was caused by a hybrid human/pig/bird flu virus that originated from dense factory farms where pigs and poultry were raised in extremely cramped conditions together. Methicillin-resistant staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), a bacteria that results in more deaths in the US than HIV/AIDS, also has strong causal link to factory pig farms. SARS-CoV-2, the virus behind the current COVID19 pandemic, may have developed in bats and later pangolins. Both species are regularly hunted for food and medicinal purposes and are sold in wet markets. Wet markets, where live animals comingle in unsanitary conditions provide the perfect environment for diseases to migrate between animals and people. Zoonosis is just one of the many threats posed by the expansion of our food system to global public health. Globally, 72% of poultry, and 55% of pork production come from concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs), or factory farms. For example, chicken CAFOs can hold up over 125,000 chickens. The close quarters and high population inside CAFOs allow the sharing of pathogens between animals with weakened immune systems. Thus, diseases spread rapidly. To safeguard their stock, CAFOs inject low doses of antibiotics into feed. This is intended to lower chances of infection, and conserve the energy animals expend to fight off bacteria in order to promote growth. This method is not without problems; antibiotics are usually administered to whole herds of animals in feed or water, which makes it impossible to ensure that every single animal receives a sufficient dose of the drug. Additionally, farms rarely use diagnostic tests to check whether they are using the right kind of antibiotic. Thus, every time an antibiotic is administered, there is a chance that bacteria develop resistance to it. Resistant bacteria can then pass from animals to humans via the food chain, or be washed into rivers and lakes. Also, bacteria can interact in the farm or in the environment, exchanging genetic information, thus increasing the pool of bacteria that is resistant to once-powerful antibiotics. Due to global trade of meat and animal products, these resistant bacteria can spread rapidly across the globe. A study sampling chicken, beef, turkey, and pork meat from 200 US supermarkets found 20% of samples contained Salmonella, with 84% of those resistant to at least one antibiotic. Another study tested 136 beef, poultry and pork samples from 36 US supermarkets and found that 25% tested positive for resistant bacteria MRSA. Fortunately, in both cases these bacteria can be eliminated with thorough cooking. Nevertheless, more than 2.8 million antibiotic-resistant infections occur in the U.S annually, resulting in more than 35 000 deaths. While antibiotic resistance has been a known issue for some time, policy responses have been mixed. The European Union has prohibited the use of antibiotics to promote growth in animals since 2016. Other parts of the world have been more lax, with nearly 80% of all the antibiotics dispensed in the US fed to livestock, and only 20% on humans. Here at home in Australia, we have one of the most conservative approaches, ranked the 5th lowest for antibiotic use in agriculture among the 29 countries examined. The factory farm system is a modern answer to a modern problem -the rapid rise in global population and demand for meat. While the economies of scale allow factory farms to be more cost-efficient and more competitive in a very crowded market, these come at the expense of every other living thing involved. Further, as our demand for meat is projected to continue rising, so will the issues associated with factory farms: environmental damage from toxic waste pollution, poor animal welfare, the exacerbation of climate change, and poor working conditions. Last year, US Senator Cory Booker unveiled the US Farm System Reform Act of 2019. One proposal from the Bill is to shut down large industrial animal operations like CAFOs. While the Bill is unlikely to pass the Republican-controlled Senate and White House, it signifies the growing public awareness of the wide-ranging problems associated with our food systems. Reducing our meat consumption also comes with personal health benefits, and reduces animal suffering, in addition to reducing the demand for factory farming and the associated health risks. That is not to say a change in dietary habit is without its barriers. Factors such as socio-economic status, access to food, and existing health problems will prevent many from drastically reducing their meat consumption. At the end of the day, our best is all we can do, but as more of us begin taking steps, however small, towards changing our diets, we will make a difference. - By Hannibal Thai *Special thanks to Ruby Green for her assistance in the writing of this post. Perhaps there is no worse way of welcoming the new decade of 2020 than the fear and loss caused by the rapid spread of COVID-19. Despite its relatively lower lethality rates (3.4% as of March 3, 2020) compared to previous similar pandemics, such as MERS (34%) and SARS (9.6%), as quickly and widely as the coronavirus has spread across the world, so too has the fear, anxiety, and worries about the virus. Lockdown procedure first took effect in Wuhan, the site where the infection was first identified, followed by Italy, and now countries around the world are enforcing varied levels of lockdown restrictions. After the lockdown in Italy and other places, photos and videos quickly circulated through social media, describing the miserable conditions of cities in lockdown. Some were left traumatised, while some others prepared in case a similar lockdown procedure was enforced by authorities in their country. Australia is no exception, experiencing the virus and the accompanying social media terror. It took only 64 days since the first case of COVID-19 was identified in Australia to record almost 4000 patients on 29th March 2020. Given the rapid escalation of the virus, people immediately began stockpiling items considered essential for survival including: canned foods, cooking oils, diapers, tissues and toilet paper. Tragedy of the Commons There is a classical notion called Tragedy of the Commons that perfectly describes the social dilemma experienced in our situation. William Lloyd was the first person to define this issue in 1833 to refer to a situation when shared resources that will be available should individuals use as according to their needs, become less available because people behave contrary to the common good of all users. Such a situation creates a vicious cycle: fear of scarcity encourages people to buy in a large quantity, and by monopolising or stockpiling certain resources, “panic buying” creates a scarcity of various goods that had previously existed only in the imagination of those panic buying. Even when individuals know that under optimal conditions the system can work to deliver the products, once a norm of stockpiling is established, it becomes a rational choice not to let oneself be the one left without critical resources. The collective buying not only affects the quantity of goods, but can also trigger aggressive behaviour as the resources become scarce. Why does scarcity stir up aggressiveness? Scarcity logically occurs when demand outweighs supply, which results in shortages, ignites competition for these resources, and increases their perceived value. Scarcity of the things that people consider essential is a perfect atmosphere for an instrumental aggressive behavior (behaviors intended to harm or injure another person as a means to obtain the resources) to occur. In performing aggressive action, individuals instinctively evaluate the cost and benefits of their action. In this case, hostile behavior is only performed if and when the fear caused by the absence of the resources outweighs the risk associated with fighting. One factor that is critical is whether there are social norms (rules or standards for behaviour) that regulate the aggression. Humans are more complex than basic survival instincts, and values and identities also contribute in determining individuals’ actions. In this sense, people whose values condemn violence and favor humanity, or whose groups have norms of sharing and cooperation, may never consider aggression as an option regardless of their perceived need for the resource in question. How to avoid the emergence of aggressive behaviour in a crisis?

In the case of stockpiling happening around us today, aggression is activated by competition for resources that are believed to be scarce. Competition often arises from worries of not being able to survive. These worries can influence us to think of others as a threat, thus providing another reason to behave aggressively. A second, more powerful reason is then created when social media and media magnify the images of aggressive behavior, creating a perceived norm of aggression that is at odds with the reality of every-day cooperation and politeness. In response to this, I believe trust is the answer, and regaining people’s trust is our main homework. Trusting that suppliers are implementing their best strategies to ensure sustainability and fair distribution of stocks is important, but most importantly, trusting that people around us are just like us, humans with full dignity and values. Highlighting our shared identities is often the bedrock of that trust: focusing on our common faith, nationality, or humanity invokes our common agenda to come together to support each other in difficult times. As soon as we show trust and respect the system by following the advice from the authorised parties, and following what the majority of people do instead of the minority, we could show the world who we actually are: a united human species whose survival is determined by shared dignities, values, and respect more than by violence. May 2020 be best remembered not by the chaos and fear caused by the COVID-19, but by the true values that defines us as humans, whose compassion, and not aggression, is what maintains our existence. - By Eunike Mutiara If you have gone through diversity and inclusion training at your workplace, watched discussions on TV about inequality or disparity of any kind, or come across articles on these issues on your timeline on social media, chances are, you have come across the word “privilege”. Privilege has been researched and written about extensively, with the focus primarily being on perceptions of privilege and separately, on socio-economic and health outcomes associated with certain social groups being privileged compared to others. However, there’s been relatively little research on understanding how it affects all of us psychologically. What is social privilege? In the academic literature, there is wide consensus that privilege encompasses 5 core components:

Types of privilege Privilege was first studied in the race and gender contexts - male privilege or White privilege being the most commonly studied and cited instances. But we now know from extensive social, health, and economic research, that there are many types of social privilege. For example:

It is important to note too, that these types of privileges do not stand alone. One form may exist in conjunction with other forms of privilege (e.g. a White man who is from an upper socio-economic background, who is also able-bodied). How does social privilege affect us all psychologically?

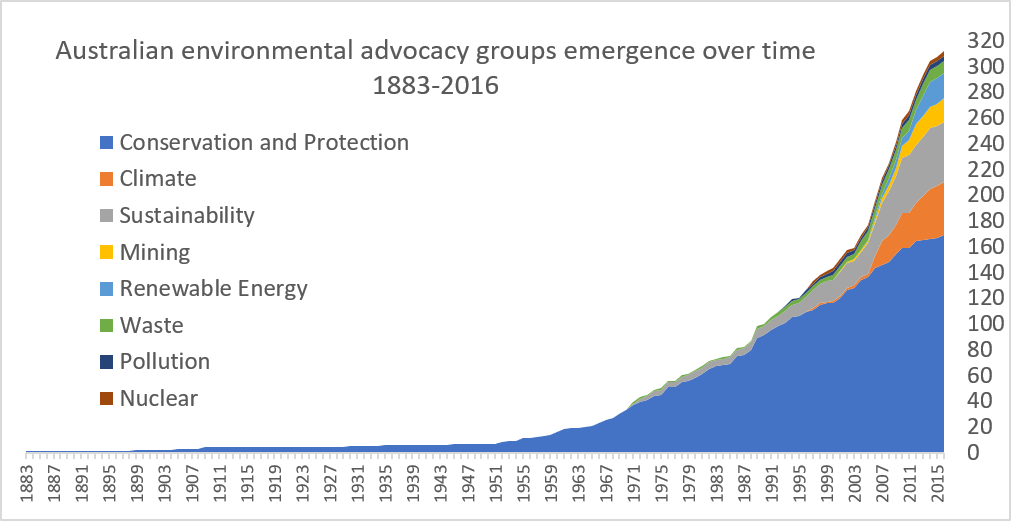

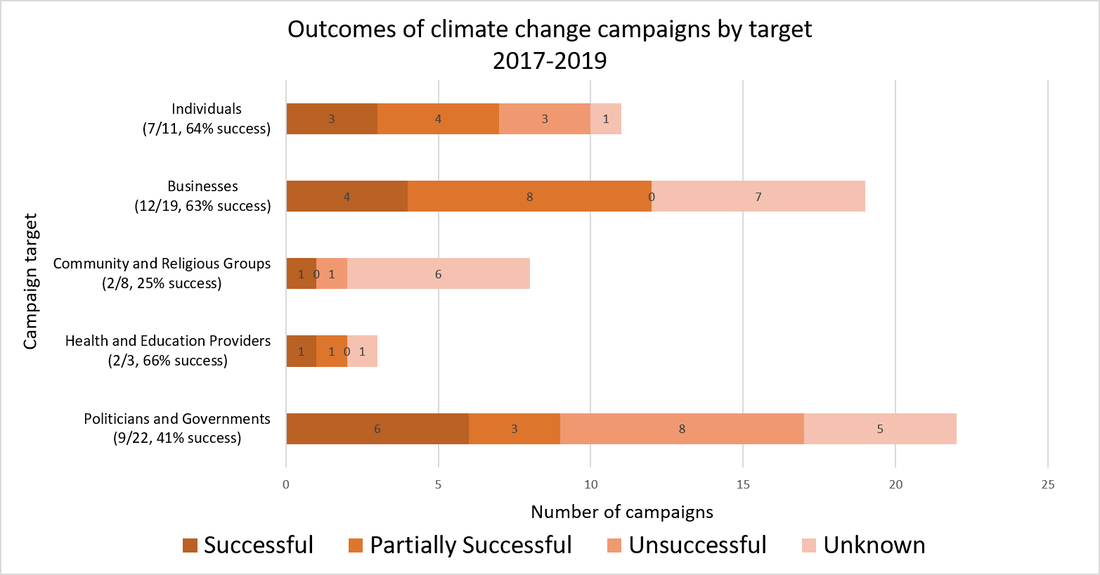

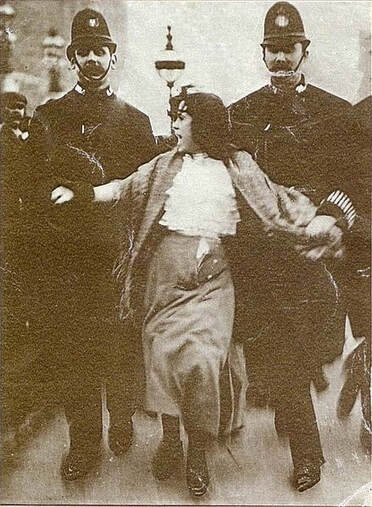

very far now”). b) Distancing oneself from the privileged group (“White privilege is a thing, but I grew up really poor and had more in common with struggling immigrants”). However, people from socially privileged groups are also known to engage in this third strategy that is positive in nature. c) Dismantling strategies (“Heteronormative privilege makes people of diverse genders and sexualities feel marginal, which is why we need to support anti-discrimination laws and marriage equality”). If reckoning with social privilege is associated with all these negative psychological experiences, why bother dealing with it? Can’t we just focus on working towards a better future for all of us? Difficult as it is to deal with the social privileges we have accrued, it has a range of important social and relational benefits! There is strong research evidence showing that for those of us who push through the discomfort of acknowledging our social privilege and the illegitimacy of it, especially in contexts where inequality and disadvantage are being discussed, we are more likely to accurately perceive instances of discrimination and disparity and forge meaningful and supportive relationships with diverse people who may not come from socially privileged groups. Further, acknowledging our privilege goes a long way in being perceived as trustworthy and supportive on issues of inequality. So it appears, that as with most things in life, effectively confronting the consequences of social privilege, requires sitting through the unpleasantness of it not avoidance of the issue. - By Tulsi Achia Every day most of us reap the benefits of collective action undertaken in the past by others. Momentous upheavals play out over centuries as the rights of some and duties of others change in tempo with changing norms and laws. We have seen this play out through history as legal slavery is abolished, disability rights are protected, and demands for Indigenous sovereignty grow. These changes ebb and flow at the macro level, the viewpoint we use to understand changes in society at large. But how do we know what the actual forces of social change are? We must understand the meso-level dynamics of groups, communities and institutions, or investigate even deeper into the micro-level influences on social change fueled by individuals and their activities. Delving into this micro world of activism is how I spent the first year of my PhD. New technologies have enabled digital humanities researchers to gather large empirical databases to investigate the characteristics of social change at the group and individual level. I used these technologies to capture what environmental movement groups and their members are doing, where they are doing it, and what they are achieving. Our findings have been published in two journal articles. Our first paper published in Environmental Communication - The Characteristics, Activities and Goals of Environmental Organizations Engaged in Advocacy Within the Australian Environmental Movement - uses data captured through a content analysis of 497 websites to show how active environmental advocates are. With over 900 campaigns and thousands of online and offline events, they have been busy advocating for environmental care for more than a hundred years. Furthermore, most of their efforts are not radical, with activists predominantly working as volunteers in our local communities with the aim to increase awareness and understanding about more pro-environmental behaviors. But activity is one thing; outcomes are another. We wanted to know whether this activity is successfully effecting change. To investigate, we went back to the micro level to ascertain the outcomes of climate change campaigns. The causes of climate change are intractable, diffuse, and woven into the fabric of our social, political and economic systems. So how do activist groups try to stop climate change, and is any one way more successful than the others? Our findings were published in the paper ‘Understanding the outcomes of climate change campaigns in the Australian environmental movement’ in the journal Case Studies in the Environment. We identified the target and goal of 58 campaigns specifically focusing on climate change and tracked their outcomes over a 2-year period. Some of these campaigns aimed to stop new coal mines. Some of them wanted government to enact new climate policies. Our data showed that almost half of these campaigns either fully or partially achieved their goal. For example, coal mines were delayed, and climate policy was enacted. In particular, 63% of campaigns asking individuals, businesses and health and education providers to reduce their climate impact were either partially or fully successful. In total 49% of all campaigns achieved full or partial success. These campaigns each only focus on one small piece of the solution to climate change and we cannot be sure how much campaign activities directly influence outcomes. Yet our research using real-world data shows that these environmental groups are connected to, and likely playing a crucial role in driving meaningful change which will help protect the environment. These activities constitute the incremental successes and failures which together drive social change. - By Robyn Gulliver Consider this troubling fact: an analysis of blogs that focus on denying climate change found that 80% of those blogs got their information from a single primary source. Worse, this source—a single individual who claims to be a “polar bear expert”—is no expert at all; they possess no formal qualifications and have conducted no research on polar bears. No matter what side of the debate you are on, this should concern you. Arguments built on false premises don’t help anyone, regardless of their beliefs or political leanings. But does this sort of widespread misinformation—involving the mere repetition of information across many sources—actually affect people's beliefs? To find out, we asked research participants to read news articles about topics that involved different governmental policies. In one experiment, participants read an article claiming that Japan’s economy would not improve, as well as one or more articles claiming the economy would improve. Unbeknownst to our participants, they were divided into three groups. The first group read four articles claiming the economy was going to improve—and importantly, each of these articles cited a different source. The second group read the same four articles, except in this case, all of the articles cited the same source (just like the climate-change-denying blogs all cite the same “expert”). And to establish a point of comparison for the other groups, the third group of participants read just one article claiming the economy would continue to improve. You might expect that when information is corroborated by multiple independent sources, it is much more likely to sway people’s opinions. If this is the case, then people who read four articles that each cited a unique source should be very certain that Japan’s economy will continue to improve. Furthermore, if people pay attention to the original sources of the information they read, then those who read four articles that all cited exactly the same source should be less certain (because that information was repeated but not corroborated). And, finally, people who read only one article claiming Japan’s economy will improve should be the least certain. Indeed, people were much more likely to believe that Japan’s economy would improve when they heard it from four unique sources than when they read only one article. But, surprisingly, people who read four articles all citing the same source were just as confident in their conclusions. Our participants seemed to pay attention only to the number of times the information was repeated without considering where the information came from. Why? Perhaps people assume that when one person is cited repeatedly, that person is the one, true expert on that topic. But, in a follow-up study, we asked other participants exactly this question: all else equal, would you rather hear from five independent sources or one single source? Unsurprisingly, most believed that more sources were better. But here's the shocking part: when those same participants then completed the task described above, they still believed the repeated information that all came from the same source just as much as independently sourced information—even for those who had just said they would prefer multiple independent sources. These results show that as we form opinions, we are influenced by the number of times we hear information repeated. Even when many claims can be traced back to a single source, we do not treat these claims as if we had heard them only once; we act as if multiple people had come to the same conclusion independently. This “illusion of consensus” presumably applies to virtually all the information that we encounter, including debates about major societal issues like gun control, vaccination, and climate change. We need to be aware of how simple biases like these affect our beliefs and behavior so that we can be better community members, make informed voting decisions, and fully participate in debates over the public good. We wanted to finish this article with a fun fact concerning the massive amount of information that people are exposed to each day. So, we asked Google: "How much information do we take in daily?", and we got a lot of answers. Try it for yourself. You'll see source after source that says you consume about 34 gigabytes of information each day. You may not know exactly how much 34 gigabytes is, but it sure sounds like a lot, and several sources told you so. What's the problem? All of these sources circle back to a single primary source. And, despite our best efforts, we weren't able to find an original source that was able to back-up these claims at all. If we weren't careful, it would have been easy to step away believing something that might not be true—and only because that information was repeated several times. So, next time you hear a rumor or watch the news, think about it. Take one moment and ask, simply, "Where is this information coming from?" - By Sami Yousif, Rosie Aboody, and Frank Keil Sami Yousif is a graduate student at Yale University. His research primarily focuses on how we see, make sense of, and navigate the space around us. In his spare time, he also studies how we (metaphorically) navigate a world of overabundant information. Rosie Aboody is a graduate student at Yale University. She studies how we learn from others. Specifically, she’s interested in how children and adults decide what others know, who to learn from, and what to believe. Frank Keil is a professor of psychology at Yale University and the director of the Cognition and Development lab. At the most general level, he is interested in how we come to make sense of the world around us. This post is previously published on the Society of Personality and Social Psychology; Character and Context Blog For Further Reading: Yousif, S. R., Aboody, R., & Keil, F. C. (2019). The illusion of consensus: a failure to distinguish between true and false consensus. Psychological Science, 30, 1195-1204. “Women are inferior to men.” “Men and women are constantly battling for power.” “Women are trying to take men’s power away.” Although sexist beliefs such as these are probably less prevalent today than in the past, they are still surprisingly prevalent, even in egalitarian societies. Researchers have fittingly dubbed such beliefs “hostile sexism”—which involves beliefs that women seek to take power away from men. A great deal of research now shows that hostile sexism is different than “benevolent sexism”—which involves the belief that women are wonderful but fragile and should be put on a pedestal by men. Although both forms of sexism can lead to discrimination against women, research shows that hostile sexism is more likely to influence overt aggression toward women in power, such as hostile derogation of female leaders, politicians, and feminists. But hostile sexism is not directed only toward female leaders, female politicians, or feminists. The everyday damage of hostile sexism may be even more pervasive in romantic heterosexual relationships. After all, we interact with our romantic partners more than anyone else. Indeed, the more men agree with hostile sexist beliefs, the more they exhibit verbal and physical aggression toward their wives and girlfriends. Why do attitudes about men’s and women’s power affect intimate relationships? Think about your own present (or past) intimate relationship. You probably depend on your partner more than anyone else for support, closeness, and intimacy, which makes romantic relationships rewarding and fulfilling. But this high level of dependence on your partner also challenges the power and control you have in your life. What your partner does affects you, and you them, and this dependence inevitably means your (and your partner’s) power is limited. Men who hold hostile sexist attitudes find this challenge to their power in romantic relationships particularly threatening. In recent research, my colleagues I and tested whether these concerns about losing power would mean that men who hold hostile sexist beliefs think they lack power in their relationships. Across four studies, involving almost 300 couples, and more than 500 individuals from the United States and New Zealand, we found that men who score high in hostile sexism think they have less power than less sexist men think they do in their romantic relationships. Moreover, these perceptions were biased in the sense that men who held greater hostile sexist beliefs underestimated the power they had over their partners compared to how much power their partners reported the men actually had. So if Jack is high in hostile sexism, he is likely to believe that Jill has more power over him than Jill reports she has. Our results suggest that men who more strongly endorse hostile sexism are more sensitive and vigilant about threats to power. This general sensitivity seems to lead men to underestimate the power they have in their own intimate relationships with women. This is important because when people think they lack power, they often behave in aggressive ways to try to restore their sense of power and control. Accordingly, across our studies, men scoring higher in hostile sexism perceived they lacked power in their relationships, which in turn predicted aggression toward their partners. This showed up on several measures of aggression—including derogatory comments, threats, and yelling at a partner during a conflict and both partners’ ratings of aggressive behaviors, such as being hurtful and critical, in their daily lives. It even applied when people recalled how aggressive they acted towards their partner over the last year. Furthermore, perceiving a lack of power—and not simply desiring to be dominant over women—explained the link between hostile sexism and relationship aggression. This is important because people often assume that sexist men feel powerful and are aggressive to maintain dominance. However, in intimate relationships, neither partner can hold all the power. Power is always shared, and both partners depend on each other. Men who are worried about losing power—that is, those who endorse hostile sexism—should find it particularly hard to navigate the power constraints in intimate relationships. Social scientists and the public often think about how sexism affects women in politics or the workplace. But hostile attitudes towards women are most routinely expressed in everyday interactions in close relationships. This research shows that sexist attitudes impact our intimate relationships, influence how we perceive our intimate relationships, and affect how we treat our partners. The aggression associated with men’s hostile sexism is obviously harmful to women, and combatting this aggression to protect women’s health and well-being is important. But this pattern of perception and behavior is also damaging for men. Being involved in relationships in which men think they lack power and behave aggressively in a bid to gain power will inevitably undermine men’s well-being as well. To cite just one example, research in health psychology suggests that experiencing chronic hostility or anger is bad for people’s cardiac health. The damage that aggression causes to intimate relationships might also reinforce hostile sexism by creating a self-fulfilling prophecy. Men who endorse hostile sexism are concerned about losing power, which promotes aggression, which then undermines women’s relationship satisfaction and commitment. The more women are dissatisfied, the more likely they are to withdraw from the relationship, express negative feelings, become less committed, and so on. These effects will not only threaten men’s power further but may also reinforce hostile attitudes that depict women as untrustworthy. This potentially damaging cycle highlights another reason why examining the impact of sexist attitudes within relationships is so important. - By Emily Cross Emily J. Cross is a postdoctoral fellow at York University in Toronto, Canada, where she studies how sexism functions in romantic heterosexual relationships. The current research was conducted with colleagues at the University of Auckland, New Zealand. This post is previously published on the Society of Personality and Social Psychology; Character and Context Blog For Further Reading Cross, E. J., Overall, N. C., Low, R. S. T., & McNulty, J. K. (2019). An interdependence account of sexism and power: Men’s hostile sexism, biased perceptions of low power, and relationship aggression. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 117(2), 338-363. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000167 Davidson, K. W., & Mostofsky, E. (2010). Anger expression and risk of coronary heart disease: Evidence from the Nova Scotia Health Survey. American heart journal, 159(2), 199–206. doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2009.11.007 I want to start by acknowledging our group’s successes In 2019, the lab saw Tracy Schultz and Cassandra Chapman awarded their PhD theses (whoohoo!). Tracy Schultz is working grimly but heroically in the Queensland department of the environment and Cassandra Chapman spent a year as a post doc in UQ’s Business School before securing a continuing T&R position there. Well done to both! It was also great fun welcoming Morgana Lizzio-Wilson as a post doc off our collective action grant (and hopefully continuing to work on the voluntary assisted dying grant in 2020): Morgana brought lots of vital energy to the lab, and I’m very grateful. 2019 also saw many other students working through their other milestones, including Hannibal, Liberty and Robin who were successfully confirmed (huzzah!), and Gi, Zahra, Kiara, Susilo, and Robyn who pushed through mid-candidature reviews and are coming up to thesis reviews. I also welcomed a new PhD student, Eunike Mutiara, who is working with Annie Pohlman in the School of Languages and Cultures at UQ on a project in genocide studies (I am an Associate Advisor). We had big health drama, with me and Tulsi both spending a lot of time away from work due to health concerns. Here’s hoping 2020 is healthy, happy and productive for us and for the group! I also want to pass on a special thank you to our volunteers and visitors for the social change lab in 2019, including Claudia Zuniga, Vladimir Bojarskich, Hema Selvanathan, Jo Brown, Tarli Young, Sam Popple, Michaels White, Dare, and Thai, Elena Gessau-Kaiser, Lea Hartwich, and Eleanor Glenn. Thank you everyone! And here’s hoping that 2020 is equally fun and social! Other news of 2019 engagement and impact With our normal collective plethora of conference presentations and journal articles (see our publications page for the latter), I continued to have great fun this year with engagement. In the environment space, I gave a few talks to universities but also state environment departments and groups such as the WWF (World Wildlife Fund). The talks argue that environmental scholars, leaders and advocates need to develop an understanding of the group processes underpinning polarisation and stalemates, because this is the new frontier of obstacles that we are facing. I reckon many established tactics of advocacy don’t actually work as desired to create a more sustainable world. We need to focus on those that avoid polarisation and stalemates, and instead grow the centre and empower conservative environmentalists. We should use evidence about effective persuasion in conflict to try to improve the outcomes of our advocacy and activism. As the year turns and the bush fires burn, as the feedback loops become more grimly clear in the oceans, ice caps, and rain forest, and as the global outlook looks worse and worse, I feel there is more appetite for new approaches among those environmental scientists, policy makers, and activists who are not drowning in despair and fury. J To mitigate despair and fury, I draw attention to new work by Robyn Gulliver coming out re what activists are doing and what successes they are obtaining. I also see a continued and increasing need for climate grief and anxiety work and I draw attention to the excellent Australian Psychological Society resources on this topic. Looking at radicalisation and extremism: thanks to the networks from our conference at UQ last year on Trajectories of Radicalisation and Deradicalisation, I was invited to a groovy conference on online radicalisation at Flinders organised by Claire Smith and others. I reconnected with many scholars there, plus meeting heaps more at the conference and at the DSTO (the defence research group) in Adelaide. I am looking forward to connecting more widely - the interdisciplinary, mixed-methods engagement is exhilarating. It was also excellent at the conference to see the strong representation from Indonesian scholars like Hamdi Muluk, Mirra Milla and their colleagues and students. There is a lot to learn from their experience and wisdom, and I am excited to visit Indonesia this year. Also on extremism, as part of my sabbatical, I visited the conflict centre at Bielefeld led by Andreas Zwick, with Arin Ayanian and others. It was truly impressive to see their interdisciplinary international assembly of conflict and radicalisation researchers, including refugee scholars sharing their expertise. I wish there were more of a consistent practice of translating the German-language output though eh. (Is it crazy to imagine a crude google translate version posted on ResearchGate, or at a uni page?) J I also visited Harvey Whitehouse’s group at Oxford, and greatly enjoyed the opportunity to give a talk at the Centre for the Study of Social Cohesion and to meet some of his brilliant students and post docs. And at St Andrews, Ken Mavor and Steve Reicher put together a gripping one day symposium on collective action: it is exciting to see the new Scottish networks that are coming together on this topic. On the sabbatical so far, I also visited Joanne Smith at Exeter, Linda Steg and Martijn van Zomeren at Groningen, Catherine Amiot at UQAM, Richard Lalonde at York, Jorida Cila and Becky Choma at Ryerson, and earlier Steve Wright and Michael Schmidt at Simon Fraser. It is very fun to spend time with these folks and their students and colleagues, and I look forward to my 2020 trips, which are listed below. Just so people know, right now as well as trying to publish the work from the DIME grant on collective action (cough cough), I am trying to work up new lines of work on norms (of course!), (in)effective advocacy and intergroup persuasion, and religion and the environment. I welcome new riffing and contacts on any of these. In other news, our lab has continued to work to take up open science practices in 2019 and to grapple with the sad reality – not new, but newly salient! – that sooo many hypotheses are disconfirmed and so many findings fail to replicate. We are seeking further consistency in pre-registration, online data sharing, transparency re analyses, and commitment to open access. Looking at articles, though, it still seems extremely rare to see acknowledgement of null findings and unexpected findings permitted, and I think this is still the great target for reviewers and editors to work on in order to propel us forward as a field. Socialchangelab.net in 2020 Within the lab, Kiara Minto has been carrying the baton passed on by Cassandra Chapman, who started the blog and website in 2018, and Zahra Mirnajafi, who also worked on it in 2019. Thank you to Kiara and Zahra for all your great work last year with our inhouse writers, our guest bloggers, and the site! I also am still active for work on Twitter, and I hope that you will follow @WlouisUQ and @socialchangelab if you are on Twitter yourself. In the meantime, we welcome each new reader of the blogs and the lab with enthusiasm, and hope to see the trend continue in 2020. What the new year holds In 2020, for face to face networking, if all goes well, I’ll be at SASP in April in Auckland, and at SPSSI in June in the USA. Please email me if you’d like to meet up. I’ll also be travelling extensively on the sabbatical – to Chile, Indonesia, New Zealand, and within Australia to Melbourne, Sydney and Adelaide. I hope people will contact me for meetings and talks if interested. Due to the sabbatical until July, I won’t be taking on new PhD students or honours students this year, but welcome expressions of interest for volunteer RAs and visitors from July onward. I’m not sure that I have as much energy as normal, what with all the travel and health dramas, but I am focusing almost exclusively on writing, talks and fun riffing until the sabbatical ends in few months, so let’s not let the time go to waste. J In Semester 2 2020, I’ll be teaching Attitudes and Social Cognition, a great third year social psychology elective, so I’m looking forward to that too. All the best from our team, Winnifred Louis Reflections on Cardinal Pell and Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse Allegations16/12/2019 In Australia, with the recent failed appeal of Cardinal Pell, the problem of child sex abuse in institutions has again been thrust into the media spotlight. Surprisingly, many continue to stand by Pell. Several prominent figures including former prime ministers Tony Abbott and John Howard publicly supported Pell. In addition, even after the failed appeal, many members of the Catholic Church have continued to argue for Pell’s innocence and the Catholic Church has refused to remove a plaque of Cardinal Pell from St Mary’s Church in Sydney despite protests. This begs the question of how can Pell’s supporters persist in believing in his innocence despite his conviction and failed appeal? My research into institutional responses to child sexual abuse may provide some insight into the question of why some continue to support Pell. We are all members of various groups and some of these groups are more important to us than others. Our group memberships can influence and bias how we respond to allegations of wrongdoing against other members of our groups. In the instance of Cardinal Pell who is one of the most powerful figures in the Catholic Church, membership in the Catholic Church may influence people’s judgements of the allegations against him and even his conviction. A theory called the “black sheep effect” suggests that when a person engages in wrongdoing, they will be judged most harshly by members of their own group in order to reject them and their behaviour and protect the reputation of the group. However, this effect is typically found in cases where the guilt is certain. In the case of Cardinal Pell, with some of the evidence withheld from the public, and as Pell maintains his innocence, the guilt cannot truly be considered certain. My research suggests that when there is any uncertainty in the guilt of the alleged offender, we are likely to see the opposite of the “the black sheep effect”. Specifically, Catholics are more likely to be protective of the accused and sceptical of the accuser. This is in line with efforts of the Catholic league to invalidate the allegations against Pell by maligning the character of the accusers. According to my research findings, the desire to protect Pell and the scepticism of his accusers would be particularly strong amongst those who identify strongly as Catholic, regardless of the quality of the evidence available. As a public figure, and staunch Catholic Tony Abbott may be particularly motivated to maintain Pell’s innocence and disbelieve allegations of child sex abuse as accepting Pell’s guilt would reflect negatively on himself and his religion. Similarly, although John Howard is not a Catholic, he is a Christian and has been personally acquainted with Cardinal Pell for several decades. Whilst it is likely that many supporters of Pell are unwilling to consider the possibility of his guilt due to subconscious biases motivating their judgements, it is also important to note that when speaking to leaders of the Catholic church, Justice Peter McClellan (head of Australia’s royal commission into child sex abuse) found that some argued that child sex abuse was a moral failure rather than a criminal act. Consequently, accepted allegations were often met with an inadequate response and the offender remained in the ministry. Recommendations for the future Given what we now know about child sex abuse in institutions, it’s clear that there has been a systematic failure for decades. My research suggests that allegations would be best dealt with by those not invested in the group of the accused. This is backed up by the recommendations of the royal commission; that those intending to enter the ministry should be subject to external psychological testing and should be removed from the ministry permanently if an allegation of sexual abuse is substantiated. Essentially, organisations should not be solely responsible for policing themselves. If you have experienced abuse within the Church or elsewhere, please contact Lifeline on 13 11 14 or one of the other help services recommended by the Royal commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse. - By Kiara Minto Protest is a common approach to the pursuit of societal change and a legal and protected procedure under the democratic system. Mobilising people to come together and express their opinion on social issues can, in some cases, push the government to create new policies. It can also attract the broader public to become engaged with particular movements (e.g., animal rights, marriage equality, clean and transparent political processes, etc.). However, some protests, especially when they involve a huge number of people are seen as a threat to public order. In many countries (e.g., Egypt, Hong Kong, Turkey, Ukraine, and Indonesia), this perceived threat to public order became the justification for handling public protest with a repressive strategy in the hope that people would withdraw their involvement in the protest. Repression is not only about the physical violence, but also the narratives produced by the government against protestors. For example, this September saw massive student protests in Indonesia, against a new act allegedly weakening the Independent Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK). In response to these protests, a repressive approach was employed by the police and authorities, not only against the protestors, but also the ministry of higher education, research, and technology, intimidating university leaders for letting their students join the protest. Despite being used by several governments, social psychology studies have revealed that repressive approaches in handling public protests are not always effective. Instead of stopping the protest by activating feelings of fear, repressive or even violent strategies employed by the authorities can drive the action to become more sustainable and garner increased participation and support for the movement. When is repression is not effective? The repressive approach exploits the power to intimidate, press, threaten or even injure. Authorities may take this approach to deal with protest actions, especially when the protest is focused on responding to political issues and perceived to threaten the interests of the political elites. Evidence shows that repressive narratives or violence conducted by the authorities can increase perceived risks in a protest’s participation. Other than that, repression can also lead to the feeling of fear and being oppressed. According to the authority’s perspective, the fear is expected to reduce or even stop the intention to participate in the following protests. Indeed, fear can be a deterrent to protesters, and violence and imprisonment can drive them off the street. However, repressive acts from the authorities are also able to strengthen the participants’ engagement with the action. Violence and repression can undermine the perceived legitimacy of the state, not just in the eyes of protestors, but in the broader community. In addition, the shared experience as victims of oppression can grow the sense of familial ties amongst protestors, as shared anxiety or fear can bring people together and strengthen the bonds of protestors. To put it simply, the previous ties that might be based on the same demands or interests are replaced by a form of kinship ties, adding a new emotional intensity to previous perceptions of solidarity. This sense of fusion or family ties creates a feeling of agency for the group, manifested in a strong tendency from every individual within the group to do something more significant on behalf of the group.The participants will be more motivated to protect their own, even risking their own life to become a shield for their fellow protestors. In the more extreme context, when the kinship bond is built amongst the protestors, and the real threats appear from the authority (e.g., police), then the tendency to make a counterattack will rise and the protest might develop into a riot. The riot is caused not just by protestors’ escalation of tactics, but by the mutual radicalisation of the police and security forces, who may cease to see the crowds as citizens worthy of protection. This pattern can be observed in the protest events in Hong Kong. Following the repressive approaches from the police, the protestors’ solidarity seems to be even greater. The individuals who do not know each other personally, through their participation in repressed protests, even become sau zuk (Cantonese term to express a very strong tie, etymologically means ‘hand and feet’) with each other. It also appears that the broader relationship between the community and the state has become more polarised and oppositional. In conclusion, activists’ efforts to create an expected social change are of course part of long-term processes. People mobilisating to raise public awareness or to encourage authorities to create more favorable policies often experience a backlash from the government, in the form of stigmatisation or even violence. In many cases, especially in a less democratic country, this repressive approach is employed out of a desire to stabilise the situation. However, an important point to consider is that this approach is often not effective. Instead of stopping their actions, the protestors experiencing collective fear and anxiety may strengthen their feelings of kinship ties and escalate their action’s intensity; the police and state actors may radicalise away from the protection of citizens to commit human rights abuses; and the broader community may come to feel the state itself is less legitimate as an authority. These are not trivial risks for a government to run. - By Susilo Wibisono When reflecting on what social change and social movements look like, images of activists protesting and engaging in other acts of civil resistance likely spring to mind for most people. However, this isn’t the only way to be a change agent. There are a myriad of ways that people can aide social change without engaging in ‘traditional’ forms of activism. In fact, we can only maximise the impact and potency of social movements if we diversify our tactics and have people ‘fighting the good fight’ in different ways. Below, I outline five common change agent roles and their effectiveness in different domains of the social change process to highlight the varied and equally valuable ways we can all contribute. The Activist The term activist can generally be understood as a person participating in collective action to further a cause or issue. Here, I focus on people who operate outside of formal systems or institutions to call public attention to injustice and agitate for social change using conventional and, in some cases, more radical tactics (e.g. Extinction Rebellion protesters blocking off bridges and main roads). When conducted appropriately, these actions can increase public support and discussion of the social issue. However, these approaches can also reinforce stereotypes that activists are ‘extreme’ which, in turn, may deter collective action participation among observers. The Insider Although activists can advocate for change outside the system, oftentimes social change messages are better received from ‘insiders’ or people who belong to the same groups or institutions that activists are trying to influence. As criticisms are trusted more when coming from ingroup members, insiders can make social change messages more palatable to the target group and may, in some cases, be able to communicate activists’ messages and concerns in terms that the ingroup can understand and be swayed by. The Scholar The Scholar’s role is twofold: to conduct rigorous and ethical research about social issues (e.g. the prevalence and impact of discrimination, the existence of anthropogenic climate change); and share this knowledge to inform public understanding of and discussions about these issues. Scholars can be academics at universities, members of research organisations (e.g. OurWatch), or, in some cases, organisations that share data about the prevalence and impact of social problems (e.g. Children by Choice publishing reports about the prevalence of Domestic Violence among their clients seeking terminations). Scholars’ ability to uniquely access and share this information can help to inform the general public’s understanding of social problems, fight misinformation, convince relevant stakeholders about the importance of an issue, and proffer evidence-based solutions. Indeed, social justice research can be used to successfully challenge and dismantle institutional prejudice and foster transformative social change by informing public policy and interventions. The Teacher An oft-overlooked role in social change is that of the teacher: a person who can foster civic engagement through formal education (e.g. primary, secondary, and/or tertiary education) or informal education (e.g. service-learning opportunities). Formal, classroom based educational interventions promote engagement with political issues and voting, while service-learning increases interest and participation in community-based action. Further, educational interventions can also be used to reduce prejudice toward disadvantaged groups. Thus, taking an active role in shaping people’s understanding of politics and social issues can positively influence their attitudes and political participation. The Constituent Constituents, or the general public, are often the numerical majority in social movements. They can include people who are sympathetic to but not committed to participating in actions for social change, or people who disagree with and resist social change messages. Unsurprisingly, constituents can greatly sway the progress of social movements, in that the attitudes and values they choose to adopt or reject influence the outcomes of state and federal elections, the types of laws and policies that governments and industries support, and broader norms in society. Thus, constituents have the power to elect leaders who support social change, call out unfair treatment and subvert anti-egalitarian norms, and support organisations and brands that make ethical choices (e.g. cruelty free cosmetics). Perhaps most importantly, other changes agents must make a considered effort to ensure that constituents have the information and support they need to make informed decisions and use their civic, relational, and economic powers effectively. Moving Forward Although the number and nature of these roles will likely vary between movements and socio-political contexts, they represent the diverse yet equally important forms of change agent work that can enhance the impact and effectiveness of social movements. The question now is: what role(s) do you play? How can you harness your unique skills and forms of influence to aid social change? Regardless of your answer, remember that just because you haven’t attended a protest or blocked oncoming traffic doesn’t mean that you aren’t a change agent. - By Morgana Lizzio-Wilson Disruptive protests gain media attention. For many people, this media attention might be the first time they learn of a particular social or environmental movement. his tactic and resulting media coverage often prompt predictable responses from the public and officials. Why, some ask, are protestors blocking roads instead of standing on the pavement educating people? Why protest if they don’t have a solution? But herein lurks a pervasive misconception of what activism actually is. Acts of civil disobedience enable awareness of a movement to bubble to the surface of daily life because they are newsworthy. However, this media attention can mask the years of relentless campaigning which builds the scaffolding to sustain these moments of shock. This scaffold is the groundwork done by the foot soldiers of a movement. Work done day after day, year after year, labouring at the often unseen toil that is the bread and butter of activism: recruiting volunteers, educating people and creating solutions. These tactics aren’t newsworthy. And sometimes to activists, they may feel like failure, creating the justification for the emergence of radical action. Does that mean that this toil was futile? Or, as argued by Extinction Rebellion, that tactics are now only just beginning? Coordinated acts of civil disobedience do not emerge spontaneously from an empty well. Take the American civil rights movement. Yes, Rosa Park’s determination to hold her bus seat created an iconic moment which helped galvanise the movement towards its goals. However, Rosa Parks was a long-term activist who, for decades, fought relentlessly against school segregation, wrongful convictions of black men, and anti-voter registration practices. Many other people had, in fact, held bus seats before her. She was one of thousands, many of whom, like her, were on the verge of exhaustion after perceiving that their years of activism had produced little change. We could look at any moment of newsworthy radical action and find parallels. Take the Salt March, an iconic moment of disobedience is now inextricably linked to the success of the Indian Independence movement. Organised as a defiant act against British rule in India, it was however, just one of the many tactics used in the 90 long years of struggle. Here in Australia, recent acts of civil disobedience for climate change action have emerged from a rich and vibrant foundation of environmentalism. Thousands of groups have been running thousands of campaigns across an array of issues. Activists have engaged in radical action against mining, logging and other destructive environmental practices for many years, using a diverse range of tactics for their cause. What were these tactics? Building groups, training volunteers, handing out flyers, organising workshops, visiting politicians, contacting polluting companies, developing policy frameworks. These tactics can successfully generate change. Almost half of the campaigns focussed on climate change achieved their goals, without the use of civil disobedience.

As social change researchers we look to understand the potential of tactics to generate change. But when we research activism, it is important to look beyond the headlines. Civil disobedience is not where ‘tactics begin’. As a movement works to raise awareness, create sympathy, motivate intentions to act, and ensure implementation, civil disobedience may instead be the end of the beginning. - By Robin Gulliver When you think about what you might learn by completing a PhD, it’s natural that you might focus on the most obvious outcome: expertise in the research topic. Sure, it is true that by the end of your PhD you will know a lot about your chosen topic but what you might not realise is that, along the way, you will also learn other important skills that are completely unrelated to the research topic. Here are the top 3 things that I learnt: 1. Dealing with uncertainty By the very nature of a research PhD, you aren’t sure what the outcome of your research is going to be when you start. The reason why you are doing the research in the first place is to answer an as yet unanswered question! Importantly however, you will realise that while sometimes your studies work out and sometimes they don’t, your PhD rolls on regardless of the outcome. So you learn to deal with the uncertainty and push on. This is a great skill to have when you are starting a new job or a new project. During such times you will inevitably feel unsure or uncertain but knowing that, with hard work and perseverance, the moment will pass is reassuring. 2. Dealing with the imposter syndrome I originally titled this sub-heading ‘Overcoming the imposter syndrome’ but that would not be true. By the end of my PhD I had not overcome the imposter syndrome but I did get to a place where it would not stop me from doing what needed to be done. What I learnt was that EVERYONE suffers from imposter syndrome, from students through to professors. Those that succeed in their careers have simply learnt how to ‘handle it’. Some tips that have helped me to ‘handle it’ are: