|

How do legislators use science? It’s not an easy question for scientists to answer. Many are hard pressed to identify even one concrete example of an evidence-based legislative action. So, we sat down with policymakers to ask them the same question. What we heard will surprise those who are pessimistic that science is used at all in policymaking. We now can identify several ways that research flows, much like a river, through the policy landscape. First, we reached out to 123 state legislators in Indiana and Wisconsin. These legislators then nominated an additional 32 colleagues who they felt were exemplary research users. We also supplemented our sample with 13 key policy players (such as governors, heads of lobbying firms, former legislators). Confidence in our findings can be inspired by the high response rates in the hard-to-access population of policymakers (60%, 84%, and 100% respectively). When Research is a Hard Sell We learned there are policies and people and places that can frustrate and facilitate research use. First, regarding policies, research was less likely to hold sway on polarized moral issues, such as reproductive rights. Research was generally less influential on issues driven by ideology, such as beliefs about whether government is the problem or the solution. There was little room for research on issues driven by passion, such as tragic personal stories. As one Republican relayed, “If a bill is named after somebody . . . like Sarah’s Bill, then you know research is screwed.” Where Research Can Have an Impact Policymakers turned to research more frequently on emerging issues such as opioid use, concussions, and rural Internet availability. Research also was more likely to influence issues where policymakers did not have established positions or where consensus had been reached, such as with the need for criminal justice reform. Research also appeared to flow more freely on the “million . . . technical issues . . . that’s really the majority of the [legislature’s] work.” One Republican, who worked on property tax assessment and land annexation, said technical issues don’t get a lot of media attention but still comprise about 80% of the policy agenda: “There’s no quote ‘Republican or Democratic’ theory about them and there’s no big contributor to your campaign who cares. . . It’s just like you’re stripping it down to the essence of good government. . . I think you have . . . much more ability to govern in sort of an evidence-based way.” Who Seeks Science However, research use varies by people. Some legislators told us they rely on intuition or gut instinct, whereas others factor in research. As an example, legislators face hundreds of bills each session, which makes it literally impossible to read and study each one. So, legislators specialize and develop expertise on a particular issue. They become known as the “go-to” legislator, whom colleagues turn to for advice on what positions to take. To attain and maintain a reputation as an issue expert, they often use in-depth research. Also, members of the minority party more often turn to research evidence; the “minority party has to win more of its arguments based upon facts” because it lacks access to other levers of power. Right Place, Right Time Timing also mattered. Research more often is used early on in the policy process when the issue is still a work in progress and policymakers have not yet staked out a position. Where the research was introduced also mattered. The most expertise on specific issues lies in committees, where bills are developed before hitting the floor. Regardless of the time or place, research is used in a political sphere where decisions are reached through negotiation. So, for policy purposes, the utility of research depends not only on its credibility to allies, but also to adversaries. Policymakers screen the credibility of research less by the methods and more by the source, particularly the source’s reputation as reliable and nonpartisan. Despite its value, policymakers believe that nonpartisan research is difficult to find. To understand research use in policymaking, we must think like a river. Policy issues infused with morality, ideology, or passion flow through narrow, nonnegotiable routes that restrict research use. However, research can navigate the policy landscape on issues that are new, technical, or open to consensus. Research use is facilitated when it enters through the port of a committee and frustrated when it enters downstream where it hits the rapids of unrelenting time pressures. To guide next steps, policymakers provided practical advice to those interested in communicating research to them. Legislators also identified multiple ways that research contributes to their effectiveness as policymakers and to the policy process. See the works listed below for more about these recommendations. - By Karen Bogenschneider & Bret N. Bogenschneider Karen Bogenschneider is a Rothermel-Bascom professor emeritus of Human Ecology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Her expertise is the study, teaching, and practice of evidence-based family policy. She is known for her work on the Family Impact Seminars, and is co-author of a forthcoming second edition of Evidence Based Policymaking: Envisioning a New Era of Theory, Research, and Practice. Bret N. Bogenschneider is an assistant professor of business law in the Luter School of Business at Christopher Newport University. His expertise is in tax law and policy, and he is author of the recently released How America was Tricked on Tax Policy. This post is previously published on the Society of Personality and Social Psychology; Character and Context Blog For Further Reading Bogenschneider, K., & Bogenschneider, B. N. (2020). Empirical evidence from state legislators: How, when, and who uses research. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 26(4) 413-424. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000232 Bogenschneider, K., Day, E., & Parrott, E. (2019). Revisiting theory on research use: Turning to policymakers for fresh insights. American Psychologist, 74(7), 778–793. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000460

0 Comments

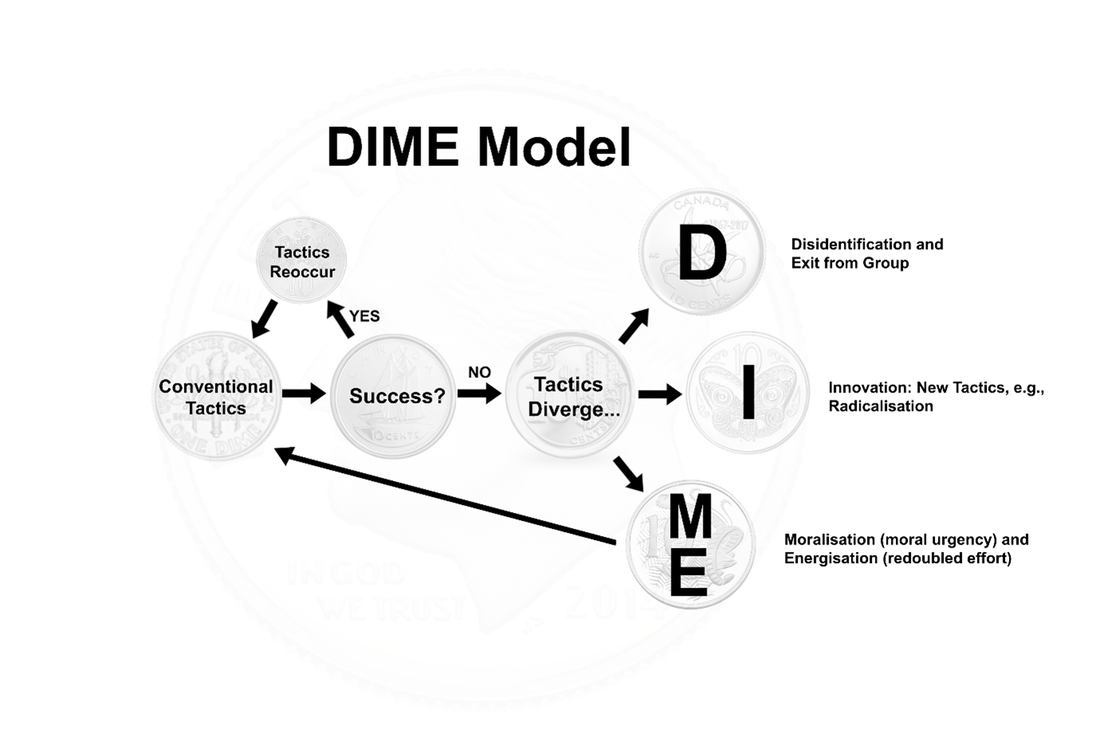

Collective action is a key process through which people try to achieve social change (e.g., School Strike 4 Climate, Black Lives Matter) or to defend the status quo. Members of social movements use a range of conventional tactics (like petitions and rallies) and radical tactics (like blockades and violence) in pursuit of their goals. In this blog post, we’re writing to introduce DIME, which seeks to model activists’ divergence in tactics. The theoretical model is published in an article on “The volatility of collective action: Theoretical analysis and empirical data”, published online here in Advances in Political Psychology. The model is named after a dime, which is a small ten cent coin in some Western currencies. In English the expressions to “stop on a dime” and “turn on a dime” both communicate an abrupt change of direction or speed. With the DIME model (Figure 1; adapted from Louis et al., 2020, p. 60), our goal was to consider the volatility of collective action, and to put forward the idea that failure diversifies social movements because the collective actors diverge onto distinct and mutually contradictory trajectories. Specifically, the DIME model proposes that after success collective actors generally persist in the original tactics. After failure, however, some actors would Disidentify (losing commitment and ultimately leaving a group). Others would seek to Innovate, leading to trajectories away from the failing tactics that could include radicalisation and deradicalisation. And a third group might double down on their pre-existing attitudes and actions, showing Moralisation, greater moral urgency and conviction, and Energisation, a desire to ramp up the pace and intensity of the existing tactics. We think these responses can all co-occur, but since they are to some extent contradictory (particularly disidentification and moralization/energization), the patterns are often masked within any one sample. They can be teased apart using person-centered analyses that look for groups of respondents with different associations among variables. Another approach could be comparing different types of participants (like people who are more and less committed to a cause) where based on past work we would expect that all three of the responses might emerge as distinct. The disidentification trajectory – getting demotivated and dropping out – has been understudied in collective action, and for groups more broadly (but see Blackwood & Louis, 2012; Becker & Tausch, 2014). A major task for leaders and committed activists is to try to reduce the likelihood of others’ disidentification by creating narratives that sustain commitment to the group in the face of failure. Inexperienced activists, those with high expectations of efficacy, and those with lower levels of identification with the cause may all be more likely to follow a disidentification or exit path. Some that drop out, furthermore, may develop hostility towards the cause they left behind. A challenge for the movement therefore is to manage the bitterness and burnout of former members. The moralization/energization path is likely to be the default path for those who were more committed to the group. In the face of obstacles, these group members will ramp up their commitment. But for how long? Attributions regarding the reason for the failure of the initial action are likely to influence the duration of persistence, we suspect: those with beliefs that the movement can grow and would be more effective if it grew may stay committed for a longer time, for example. In contrast, attributions that failures are due to decision-makers’ corruption or opponents’ intractability may lay the groundwork for taking an innovation pathway. A challenge for the leadership and movement is to understand the reasons for the movement failures as they occur, and to communicate accurate and motivating theories of change that sustain mobilisation. Finally, the innovation path as we conceive it may lead from conventional to radical action (radicalisation), or from radical back to conventional (deradicalisation). It may also lead away from political action altogether, towards more internally focused solidarity and support for ingroup members, or towards movements of creative truth-telling and art. There may be individual difference factors that promote this pathway, but it is also a direction where leadership and contestation of the group’s norms would normally take place, as group members dispute whether the innovation is called for and what new forms of action the group should support. The DIME model aims to answer the call to theorise about the volatility of collective action and the dynamic changes that so clearly occur. It also contributes to a growing body of work that is exploring the nature of radicalisation and deradicalisation. We look forward to engaging with other scholars who have a vision of work in this space. - By Professor Winnifred Louis Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you’ve probably heard that there is a crisis of confidence in the charity sector. In recent years a series of high-profile scandals have rocked the sector, including the Oxfam sexual exploitation scandal and the suicide of an elderly British donor Olive Cooke, who had received an estimated 3,000 charity appeals in the year before her death. Scholars, practitioners, and the media have lamented falling trust in charities and worried about the ramifications for the nonprofit sector. Trust is known to be an essential ingredient for fundraising success. Drops in charity confidence could therefore threaten the survival of the sector as a whole. My colleagues and I study charity scandals and trust in nonprofits. Through a series of experiments, we have demonstrated that scandals emerging within nonprofits have dire consequences for transgressing organizations. In fact, nonprofits lose trust and consumer support at faster rates after a scandal than commercial organizations do. It’s clear that scandals damage trust in particular organizations. But do highly publicized scandals also damage trust in the sector as a whole? To answer this question, we accessed global data collected as part of the Edelman Trust Barometer. Each year, Edelman survey people around the word and ask, among other things, how much they “trust NGOs in general to do what is right”. Edelman shared data from 294,176 people in 31 countries over a period of 9 consecutive years. We analyzed these data in a way that had not been done before. Specifically, we looked at trust trends after taking into account individual differences (i.e., the fact that some kinds of people are more or less trusting) and country differences (i.e. the fact that some countries are generally more or less trusting and that different countries may show different trust trends over time). Spoiler: There is no global crisis of trust in nonprofits Our analysis shows no significant decrease in trust over time. In fact, once we accounted for individual and country differences, trust in NGOs has actually increased slightly around the globe between 2011 and 2019. It’s true that some people and countries show different trends. For example, the increase in trust was sharper among men, people aged under 40 years, and people with higher education, income, and media consumption. Although some countries showed small increases and some showed small decreases in trust, none of these trends was substantial in size. In other words, there is no was no evidence that trust in NGOs has changed meaningfully in any of the 31 countries over the last decade. So why do the public still trust nonprofits despite the scandals? The short answer is we don’t know. The data allowed us to identify if trust was changing over time but not why. We have some ideas about what might be going on though. Charities, generally speaking, have reputations for being moral. We suspect that this good reputation functions as a kind of “trust bank” that buffers charities from the effects of scandals. Perhaps over time the sector makes deposits in the community trust bank through their good works in society. When scandals emerge within individual organizations, this may draw down some of the community trust that has built up over time but have very little impact on reserves of trust in the overall sector. What does this mean for nonprofit managers? If the good deeds of charities cultivate trust banks from which they can safely draw on in times of crisis—an idea that has not yet been evidenced—then a key strategy will be to ensure all successes are communicated both to the supporter base and to the wider public. Nonprofit leaders should also encourage other organizations within the sector to do the same. When the nonprofit sector works together to highlight their good works, the entire sector may benefit in the future when unexpected scandals erupt within the community. - Dr Cassandra Chapman *** This article was reposted with permission from the NVSQ Blog. Read the full article: Chapman, C. M., Hornsey, M. J., & Gillespie, N. (2020). No global crisis of trust: A longitudinal and multinational examination of public trust in nonprofits. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly. doi: 10.1177/0899764020962221 You did, so you can, and you will – how self-efficacy guides adoption of difficult behaviour.29/6/2020 How can people become more environmentally sustainable? One theory that describes how human behaviour may be influenced is behavioural spillover. Spillover is the notion that doing one behaviour triggers adoption of other behaviours. It’s the idea that engaging in certain behaviours can put you on a ‘virtuous escalator’, where you keep doing more and more. Spillover has grabbed the attention of researchers and policy makers since it offers a cost-efficient, self-sustaining form of behaviour change that when understood properly could be harnessed for fostering the adoption of desirable behaviour. Spillover as a concept is intuitive, since it ‘makes sense’ that one behaviour may influence another. Yet spillover as a phenomenon is far more elusive than intuitive, since there are a growing number of studies with mixed findings about whether or not spillover occurs. The important question within spillover research these days is “how can spillover be encouraged?” We were interested in one particular mechanism: self-efficacy. Self-efficacy is the belief that you are capable enough to be able to do a certain behaviour. We were interested in self-efficacy as a spillover mechanism since it is theorised to have a bi-directional relationship with behaviour. Self-efficacy is influenced by what you have done in the past and self-efficacy influences what you choose to do in the future (known as reciprocal determinism).

Across 2 studies with Australian participants, we explored whether self-efficacy may be a potential mechanism for fostering behavioural spillover. In the first study, information was gathered on participants’ past engagement and intended engagement in 10 water-related behaviours (i.e., behaviours that influence water use, such as water conservation/efficiency and water quality protection behaviours). A pilot study showed that 6 of these behaviours were considered ‘easy’ to do and 4 were considered ‘difficult’ to do. We also measured participants’ sense of self-efficacy towards protecting water quality and conserving water (e.g., I feel confident I can engage in ways to protect water quality). We found that the easy behaviours people have done in the past were related to their sense of self-efficacy, and this greater sense of confidence was associated with increased intentions for more difficult behaviour in the future. These findings were exciting, but two questions remained: 1) is self-efficacy a consistent spillover mechanism? E.g., can we find the effect again? And 2) can this effect lead to actual behaviour? To answers these questions, we used data collected over two occasions with Australian householders that reported whether they were participating in certain water-reducing behaviours and had installed water efficiency devices (e.g., water tank, water efficient washer). Similar to the findings of Study 1, we found that the more water reduction behaviours (i.e., easy behaviours) householders had adopted, the greater their self-efficacy, and the greater their intentions for installing water efficiency devices (i.e., difficult behaviours), in turn, the more of these water efficient devices were actually installed. In lay peoples’ terms, we found that the easy things people had been doing fed into their self-efficacy, which increased their intentions and actual adoption of more difficult behaviour. Ultimately these findings demonstrate support for the idea that self-efficacy may be a mechanism that encourages spillover. These two studies demonstrate associations between past behaviour, self-efficacy, and intended and actual future behaviour, shedding some light on a potential mechanism of spillover. Further testing in real-world settings is needed to understand if self-efficacy can be harnessed and used to inspire adoption of more impactful behaviour. What these findings do suggest is that “from little things, big things grow”! The things we do, even if they are easy and simple, help us to gain the confidence to take on more difficult behaviours in the future. - By Nita Lauren Lauren, N., Fielding, K. S., Smith, L., & Louis, W. R. (2016). You did, so you can and you will: Self-efficacy as a mediator of spillover from easy to more difficult pro-environmental behaviour. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 48, 191-199. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.10.004 Facing COVID-19, communities are trying to strike the balance between locking each other out and keeping each other safe. As government experts and political commentators examine the art of public health messaging for effective behaviour change, lessons could and should be drawn from the most devastating health emergency in recent times: the 2013-2016 Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) epidemic in western Africa. EVD had an incredibly high death rate (50%) and broke out in countries with severely under-resourced healthcare and little public health access. During the EVD epidemic, communities faced similar challenges as with COVID-19, though with even more deadly consequences. Multiagency reports show that early in 2014, EVD public health messaging was understood, but failed to motivate meaningful behavioural change. For example:

Why comprehension may not result in action During an emergency, the individual’s ability to shape what is happening to them is severely reduced. This loss of control leads to a perceived reduction in personal efficacy (an inability to produce desired effects and forestall undesired effects by their actions), leaving individuals with little motivation to act. Social psychological researcher Bandura argues that due to an increasingly interdependent world, people will turn to their communities to accomplish what they cannot individually. Perceived collective efficacy will subsequently determine how confident or discouraged they are to tackle bigger societal problems. In countries with strong emergency infrastructure, however, individuals may turn to state proxies instead of the collective. They may call an ambulance, fire services, or police to assist them in overcoming a challenge they cannot, rather than a neighbour. The proxy replaces the collective. Therefore, it may be argued that collective action during an emergency is made redundant by the state-led initiative. If this were the case with COVID-19, epidemiologists speaking from a government platform via the national broadcaster should command public compliance. Yet, in many cases they do not. Similar patterns were also borne out during the EVD epidemic. Studies confirm that the disconnect between individual comprehension of public health messaging and meaningful behavioural change, was due to a failure of national and international responders to address community practices. That is, national and international leadership overlooked potential collective solutions at the community level, with fatal consequences for those communities. In the latter part of 2014 community health workers and local journalists intervened. To confront EVD, these groups translated public health messaging through a community lens, directly addressing rumours and misinformation. Within six months of community interventions, humanitarian agencies reported significant improvements in prevention measures; over 95% of EVD patients presented to health facilities within 24 hours of experiencing symptoms. Emergency response organisations were able to leverage understanding of local explanatory models, history of previous emergencies, beliefs, practices, and politics through community health workers. Contact tracing and education campaigns were undertaken by local volunteers. Together with religious authorities, new burial practices were enacted. Especially in countries with developed health systems, the COVID-19 response has largely overlooked community responses. The focus on unified top-down policy is important, but the efficacy may be limited as during EVD. Collective efficacy is key to mobilise to save lives and keep each other safe. - By Siobhán McEvoy & Laura K Taylor Laura K. Taylor (PhD) is an Assistant Professor, School of Psychology, University College Dublin (Ireland) and Queen's University Belfast (Northern Ireland). Her research integrates peace studies with developmental and social psychology to study how to promote constructive intergroup relations and peacebuilding among children and youth in divided societies. Siobhan McEvoy is a humanitarian consultant specialising in social mobilisation and community engagement with people displaced due to conflict. Her work has included tackling misinformation during migration of refugees in southern Europe, understanding the use of Rohingya language in responding to health emergencies in refugee camps in Bangladesh and creating strategy for community mobilisation in South Sudan to prevent the spread of Ebola virus disease. Perhaps there is no worse way of welcoming the new decade of 2020 than the fear and loss caused by the rapid spread of COVID-19. Despite its relatively lower lethality rates (3.4% as of March 3, 2020) compared to previous similar pandemics, such as MERS (34%) and SARS (9.6%), as quickly and widely as the coronavirus has spread across the world, so too has the fear, anxiety, and worries about the virus. Lockdown procedure first took effect in Wuhan, the site where the infection was first identified, followed by Italy, and now countries around the world are enforcing varied levels of lockdown restrictions. After the lockdown in Italy and other places, photos and videos quickly circulated through social media, describing the miserable conditions of cities in lockdown. Some were left traumatised, while some others prepared in case a similar lockdown procedure was enforced by authorities in their country. Australia is no exception, experiencing the virus and the accompanying social media terror. It took only 64 days since the first case of COVID-19 was identified in Australia to record almost 4000 patients on 29th March 2020. Given the rapid escalation of the virus, people immediately began stockpiling items considered essential for survival including: canned foods, cooking oils, diapers, tissues and toilet paper. Tragedy of the Commons There is a classical notion called Tragedy of the Commons that perfectly describes the social dilemma experienced in our situation. William Lloyd was the first person to define this issue in 1833 to refer to a situation when shared resources that will be available should individuals use as according to their needs, become less available because people behave contrary to the common good of all users. Such a situation creates a vicious cycle: fear of scarcity encourages people to buy in a large quantity, and by monopolising or stockpiling certain resources, “panic buying” creates a scarcity of various goods that had previously existed only in the imagination of those panic buying. Even when individuals know that under optimal conditions the system can work to deliver the products, once a norm of stockpiling is established, it becomes a rational choice not to let oneself be the one left without critical resources. The collective buying not only affects the quantity of goods, but can also trigger aggressive behaviour as the resources become scarce. Why does scarcity stir up aggressiveness? Scarcity logically occurs when demand outweighs supply, which results in shortages, ignites competition for these resources, and increases their perceived value. Scarcity of the things that people consider essential is a perfect atmosphere for an instrumental aggressive behavior (behaviors intended to harm or injure another person as a means to obtain the resources) to occur. In performing aggressive action, individuals instinctively evaluate the cost and benefits of their action. In this case, hostile behavior is only performed if and when the fear caused by the absence of the resources outweighs the risk associated with fighting. One factor that is critical is whether there are social norms (rules or standards for behaviour) that regulate the aggression. Humans are more complex than basic survival instincts, and values and identities also contribute in determining individuals’ actions. In this sense, people whose values condemn violence and favor humanity, or whose groups have norms of sharing and cooperation, may never consider aggression as an option regardless of their perceived need for the resource in question. How to avoid the emergence of aggressive behaviour in a crisis?

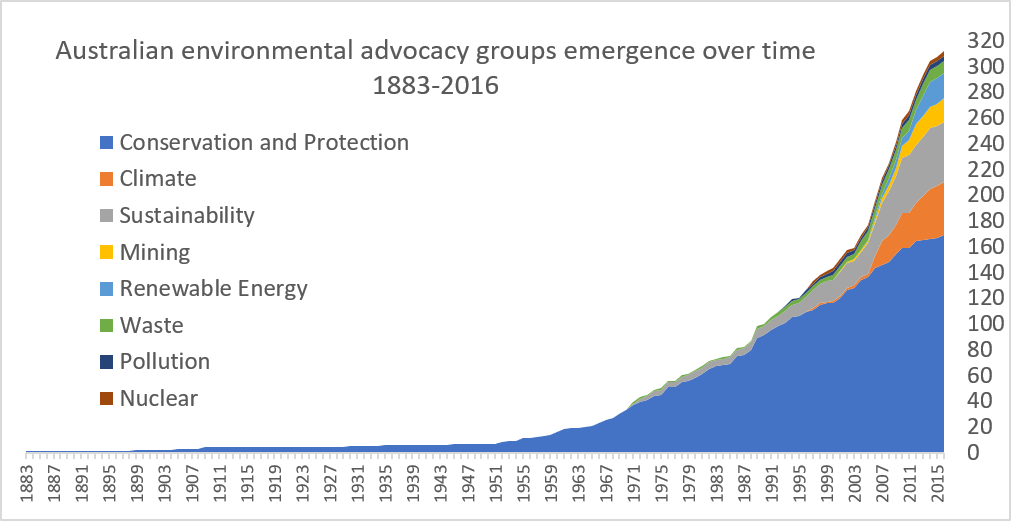

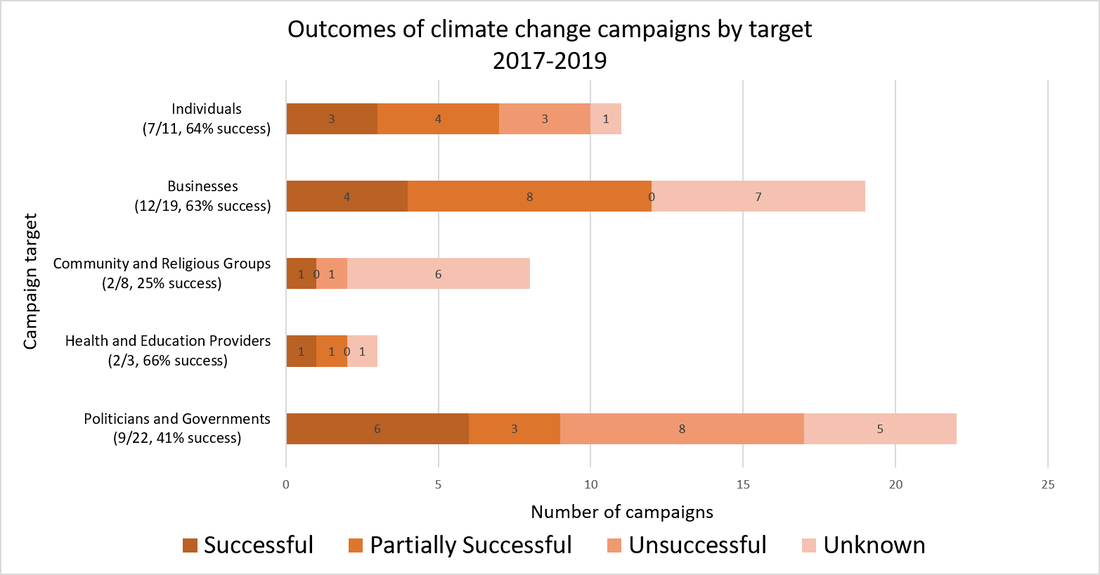

In the case of stockpiling happening around us today, aggression is activated by competition for resources that are believed to be scarce. Competition often arises from worries of not being able to survive. These worries can influence us to think of others as a threat, thus providing another reason to behave aggressively. A second, more powerful reason is then created when social media and media magnify the images of aggressive behavior, creating a perceived norm of aggression that is at odds with the reality of every-day cooperation and politeness. In response to this, I believe trust is the answer, and regaining people’s trust is our main homework. Trusting that suppliers are implementing their best strategies to ensure sustainability and fair distribution of stocks is important, but most importantly, trusting that people around us are just like us, humans with full dignity and values. Highlighting our shared identities is often the bedrock of that trust: focusing on our common faith, nationality, or humanity invokes our common agenda to come together to support each other in difficult times. As soon as we show trust and respect the system by following the advice from the authorised parties, and following what the majority of people do instead of the minority, we could show the world who we actually are: a united human species whose survival is determined by shared dignities, values, and respect more than by violence. May 2020 be best remembered not by the chaos and fear caused by the COVID-19, but by the true values that defines us as humans, whose compassion, and not aggression, is what maintains our existence. - By Eunike Mutiara Every day most of us reap the benefits of collective action undertaken in the past by others. Momentous upheavals play out over centuries as the rights of some and duties of others change in tempo with changing norms and laws. We have seen this play out through history as legal slavery is abolished, disability rights are protected, and demands for Indigenous sovereignty grow. These changes ebb and flow at the macro level, the viewpoint we use to understand changes in society at large. But how do we know what the actual forces of social change are? We must understand the meso-level dynamics of groups, communities and institutions, or investigate even deeper into the micro-level influences on social change fueled by individuals and their activities. Delving into this micro world of activism is how I spent the first year of my PhD. New technologies have enabled digital humanities researchers to gather large empirical databases to investigate the characteristics of social change at the group and individual level. I used these technologies to capture what environmental movement groups and their members are doing, where they are doing it, and what they are achieving. Our findings have been published in two journal articles. Our first paper published in Environmental Communication - The Characteristics, Activities and Goals of Environmental Organizations Engaged in Advocacy Within the Australian Environmental Movement - uses data captured through a content analysis of 497 websites to show how active environmental advocates are. With over 900 campaigns and thousands of online and offline events, they have been busy advocating for environmental care for more than a hundred years. Furthermore, most of their efforts are not radical, with activists predominantly working as volunteers in our local communities with the aim to increase awareness and understanding about more pro-environmental behaviors. But activity is one thing; outcomes are another. We wanted to know whether this activity is successfully effecting change. To investigate, we went back to the micro level to ascertain the outcomes of climate change campaigns. The causes of climate change are intractable, diffuse, and woven into the fabric of our social, political and economic systems. So how do activist groups try to stop climate change, and is any one way more successful than the others? Our findings were published in the paper ‘Understanding the outcomes of climate change campaigns in the Australian environmental movement’ in the journal Case Studies in the Environment. We identified the target and goal of 58 campaigns specifically focusing on climate change and tracked their outcomes over a 2-year period. Some of these campaigns aimed to stop new coal mines. Some of them wanted government to enact new climate policies. Our data showed that almost half of these campaigns either fully or partially achieved their goal. For example, coal mines were delayed, and climate policy was enacted. In particular, 63% of campaigns asking individuals, businesses and health and education providers to reduce their climate impact were either partially or fully successful. In total 49% of all campaigns achieved full or partial success. These campaigns each only focus on one small piece of the solution to climate change and we cannot be sure how much campaign activities directly influence outcomes. Yet our research using real-world data shows that these environmental groups are connected to, and likely playing a crucial role in driving meaningful change which will help protect the environment. These activities constitute the incremental successes and failures which together drive social change. - By Robyn Gulliver I want to start by acknowledging our group’s successes In 2019, the lab saw Tracy Schultz and Cassandra Chapman awarded their PhD theses (whoohoo!). Tracy Schultz is working grimly but heroically in the Queensland department of the environment and Cassandra Chapman spent a year as a post doc in UQ’s Business School before securing a continuing T&R position there. Well done to both! It was also great fun welcoming Morgana Lizzio-Wilson as a post doc off our collective action grant (and hopefully continuing to work on the voluntary assisted dying grant in 2020): Morgana brought lots of vital energy to the lab, and I’m very grateful. 2019 also saw many other students working through their other milestones, including Hannibal, Liberty and Robin who were successfully confirmed (huzzah!), and Gi, Zahra, Kiara, Susilo, and Robyn who pushed through mid-candidature reviews and are coming up to thesis reviews. I also welcomed a new PhD student, Eunike Mutiara, who is working with Annie Pohlman in the School of Languages and Cultures at UQ on a project in genocide studies (I am an Associate Advisor). We had big health drama, with me and Tulsi both spending a lot of time away from work due to health concerns. Here’s hoping 2020 is healthy, happy and productive for us and for the group! I also want to pass on a special thank you to our volunteers and visitors for the social change lab in 2019, including Claudia Zuniga, Vladimir Bojarskich, Hema Selvanathan, Jo Brown, Tarli Young, Sam Popple, Michaels White, Dare, and Thai, Elena Gessau-Kaiser, Lea Hartwich, and Eleanor Glenn. Thank you everyone! And here’s hoping that 2020 is equally fun and social! Other news of 2019 engagement and impact With our normal collective plethora of conference presentations and journal articles (see our publications page for the latter), I continued to have great fun this year with engagement. In the environment space, I gave a few talks to universities but also state environment departments and groups such as the WWF (World Wildlife Fund). The talks argue that environmental scholars, leaders and advocates need to develop an understanding of the group processes underpinning polarisation and stalemates, because this is the new frontier of obstacles that we are facing. I reckon many established tactics of advocacy don’t actually work as desired to create a more sustainable world. We need to focus on those that avoid polarisation and stalemates, and instead grow the centre and empower conservative environmentalists. We should use evidence about effective persuasion in conflict to try to improve the outcomes of our advocacy and activism. As the year turns and the bush fires burn, as the feedback loops become more grimly clear in the oceans, ice caps, and rain forest, and as the global outlook looks worse and worse, I feel there is more appetite for new approaches among those environmental scientists, policy makers, and activists who are not drowning in despair and fury. J To mitigate despair and fury, I draw attention to new work by Robyn Gulliver coming out re what activists are doing and what successes they are obtaining. I also see a continued and increasing need for climate grief and anxiety work and I draw attention to the excellent Australian Psychological Society resources on this topic. Looking at radicalisation and extremism: thanks to the networks from our conference at UQ last year on Trajectories of Radicalisation and Deradicalisation, I was invited to a groovy conference on online radicalisation at Flinders organised by Claire Smith and others. I reconnected with many scholars there, plus meeting heaps more at the conference and at the DSTO (the defence research group) in Adelaide. I am looking forward to connecting more widely - the interdisciplinary, mixed-methods engagement is exhilarating. It was also excellent at the conference to see the strong representation from Indonesian scholars like Hamdi Muluk, Mirra Milla and their colleagues and students. There is a lot to learn from their experience and wisdom, and I am excited to visit Indonesia this year. Also on extremism, as part of my sabbatical, I visited the conflict centre at Bielefeld led by Andreas Zwick, with Arin Ayanian and others. It was truly impressive to see their interdisciplinary international assembly of conflict and radicalisation researchers, including refugee scholars sharing their expertise. I wish there were more of a consistent practice of translating the German-language output though eh. (Is it crazy to imagine a crude google translate version posted on ResearchGate, or at a uni page?) J I also visited Harvey Whitehouse’s group at Oxford, and greatly enjoyed the opportunity to give a talk at the Centre for the Study of Social Cohesion and to meet some of his brilliant students and post docs. And at St Andrews, Ken Mavor and Steve Reicher put together a gripping one day symposium on collective action: it is exciting to see the new Scottish networks that are coming together on this topic. On the sabbatical so far, I also visited Joanne Smith at Exeter, Linda Steg and Martijn van Zomeren at Groningen, Catherine Amiot at UQAM, Richard Lalonde at York, Jorida Cila and Becky Choma at Ryerson, and earlier Steve Wright and Michael Schmidt at Simon Fraser. It is very fun to spend time with these folks and their students and colleagues, and I look forward to my 2020 trips, which are listed below. Just so people know, right now as well as trying to publish the work from the DIME grant on collective action (cough cough), I am trying to work up new lines of work on norms (of course!), (in)effective advocacy and intergroup persuasion, and religion and the environment. I welcome new riffing and contacts on any of these. In other news, our lab has continued to work to take up open science practices in 2019 and to grapple with the sad reality – not new, but newly salient! – that sooo many hypotheses are disconfirmed and so many findings fail to replicate. We are seeking further consistency in pre-registration, online data sharing, transparency re analyses, and commitment to open access. Looking at articles, though, it still seems extremely rare to see acknowledgement of null findings and unexpected findings permitted, and I think this is still the great target for reviewers and editors to work on in order to propel us forward as a field. Socialchangelab.net in 2020 Within the lab, Kiara Minto has been carrying the baton passed on by Cassandra Chapman, who started the blog and website in 2018, and Zahra Mirnajafi, who also worked on it in 2019. Thank you to Kiara and Zahra for all your great work last year with our inhouse writers, our guest bloggers, and the site! I also am still active for work on Twitter, and I hope that you will follow @WlouisUQ and @socialchangelab if you are on Twitter yourself. In the meantime, we welcome each new reader of the blogs and the lab with enthusiasm, and hope to see the trend continue in 2020. What the new year holds In 2020, for face to face networking, if all goes well, I’ll be at SASP in April in Auckland, and at SPSSI in June in the USA. Please email me if you’d like to meet up. I’ll also be travelling extensively on the sabbatical – to Chile, Indonesia, New Zealand, and within Australia to Melbourne, Sydney and Adelaide. I hope people will contact me for meetings and talks if interested. Due to the sabbatical until July, I won’t be taking on new PhD students or honours students this year, but welcome expressions of interest for volunteer RAs and visitors from July onward. I’m not sure that I have as much energy as normal, what with all the travel and health dramas, but I am focusing almost exclusively on writing, talks and fun riffing until the sabbatical ends in few months, so let’s not let the time go to waste. J In Semester 2 2020, I’ll be teaching Attitudes and Social Cognition, a great third year social psychology elective, so I’m looking forward to that too. All the best from our team, Winnifred Louis Protest is a common approach to the pursuit of societal change and a legal and protected procedure under the democratic system. Mobilising people to come together and express their opinion on social issues can, in some cases, push the government to create new policies. It can also attract the broader public to become engaged with particular movements (e.g., animal rights, marriage equality, clean and transparent political processes, etc.). However, some protests, especially when they involve a huge number of people are seen as a threat to public order. In many countries (e.g., Egypt, Hong Kong, Turkey, Ukraine, and Indonesia), this perceived threat to public order became the justification for handling public protest with a repressive strategy in the hope that people would withdraw their involvement in the protest. Repression is not only about the physical violence, but also the narratives produced by the government against protestors. For example, this September saw massive student protests in Indonesia, against a new act allegedly weakening the Independent Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK). In response to these protests, a repressive approach was employed by the police and authorities, not only against the protestors, but also the ministry of higher education, research, and technology, intimidating university leaders for letting their students join the protest. Despite being used by several governments, social psychology studies have revealed that repressive approaches in handling public protests are not always effective. Instead of stopping the protest by activating feelings of fear, repressive or even violent strategies employed by the authorities can drive the action to become more sustainable and garner increased participation and support for the movement. When is repression is not effective? The repressive approach exploits the power to intimidate, press, threaten or even injure. Authorities may take this approach to deal with protest actions, especially when the protest is focused on responding to political issues and perceived to threaten the interests of the political elites. Evidence shows that repressive narratives or violence conducted by the authorities can increase perceived risks in a protest’s participation. Other than that, repression can also lead to the feeling of fear and being oppressed. According to the authority’s perspective, the fear is expected to reduce or even stop the intention to participate in the following protests. Indeed, fear can be a deterrent to protesters, and violence and imprisonment can drive them off the street. However, repressive acts from the authorities are also able to strengthen the participants’ engagement with the action. Violence and repression can undermine the perceived legitimacy of the state, not just in the eyes of protestors, but in the broader community. In addition, the shared experience as victims of oppression can grow the sense of familial ties amongst protestors, as shared anxiety or fear can bring people together and strengthen the bonds of protestors. To put it simply, the previous ties that might be based on the same demands or interests are replaced by a form of kinship ties, adding a new emotional intensity to previous perceptions of solidarity. This sense of fusion or family ties creates a feeling of agency for the group, manifested in a strong tendency from every individual within the group to do something more significant on behalf of the group.The participants will be more motivated to protect their own, even risking their own life to become a shield for their fellow protestors. In the more extreme context, when the kinship bond is built amongst the protestors, and the real threats appear from the authority (e.g., police), then the tendency to make a counterattack will rise and the protest might develop into a riot. The riot is caused not just by protestors’ escalation of tactics, but by the mutual radicalisation of the police and security forces, who may cease to see the crowds as citizens worthy of protection. This pattern can be observed in the protest events in Hong Kong. Following the repressive approaches from the police, the protestors’ solidarity seems to be even greater. The individuals who do not know each other personally, through their participation in repressed protests, even become sau zuk (Cantonese term to express a very strong tie, etymologically means ‘hand and feet’) with each other. It also appears that the broader relationship between the community and the state has become more polarised and oppositional. In conclusion, activists’ efforts to create an expected social change are of course part of long-term processes. People mobilisating to raise public awareness or to encourage authorities to create more favorable policies often experience a backlash from the government, in the form of stigmatisation or even violence. In many cases, especially in a less democratic country, this repressive approach is employed out of a desire to stabilise the situation. However, an important point to consider is that this approach is often not effective. Instead of stopping their actions, the protestors experiencing collective fear and anxiety may strengthen their feelings of kinship ties and escalate their action’s intensity; the police and state actors may radicalise away from the protection of citizens to commit human rights abuses; and the broader community may come to feel the state itself is less legitimate as an authority. These are not trivial risks for a government to run. - By Susilo Wibisono When reflecting on what social change and social movements look like, images of activists protesting and engaging in other acts of civil resistance likely spring to mind for most people. However, this isn’t the only way to be a change agent. There are a myriad of ways that people can aide social change without engaging in ‘traditional’ forms of activism. In fact, we can only maximise the impact and potency of social movements if we diversify our tactics and have people ‘fighting the good fight’ in different ways. Below, I outline five common change agent roles and their effectiveness in different domains of the social change process to highlight the varied and equally valuable ways we can all contribute. The Activist The term activist can generally be understood as a person participating in collective action to further a cause or issue. Here, I focus on people who operate outside of formal systems or institutions to call public attention to injustice and agitate for social change using conventional and, in some cases, more radical tactics (e.g. Extinction Rebellion protesters blocking off bridges and main roads). When conducted appropriately, these actions can increase public support and discussion of the social issue. However, these approaches can also reinforce stereotypes that activists are ‘extreme’ which, in turn, may deter collective action participation among observers. The Insider Although activists can advocate for change outside the system, oftentimes social change messages are better received from ‘insiders’ or people who belong to the same groups or institutions that activists are trying to influence. As criticisms are trusted more when coming from ingroup members, insiders can make social change messages more palatable to the target group and may, in some cases, be able to communicate activists’ messages and concerns in terms that the ingroup can understand and be swayed by. The Scholar The Scholar’s role is twofold: to conduct rigorous and ethical research about social issues (e.g. the prevalence and impact of discrimination, the existence of anthropogenic climate change); and share this knowledge to inform public understanding of and discussions about these issues. Scholars can be academics at universities, members of research organisations (e.g. OurWatch), or, in some cases, organisations that share data about the prevalence and impact of social problems (e.g. Children by Choice publishing reports about the prevalence of Domestic Violence among their clients seeking terminations). Scholars’ ability to uniquely access and share this information can help to inform the general public’s understanding of social problems, fight misinformation, convince relevant stakeholders about the importance of an issue, and proffer evidence-based solutions. Indeed, social justice research can be used to successfully challenge and dismantle institutional prejudice and foster transformative social change by informing public policy and interventions. The Teacher An oft-overlooked role in social change is that of the teacher: a person who can foster civic engagement through formal education (e.g. primary, secondary, and/or tertiary education) or informal education (e.g. service-learning opportunities). Formal, classroom based educational interventions promote engagement with political issues and voting, while service-learning increases interest and participation in community-based action. Further, educational interventions can also be used to reduce prejudice toward disadvantaged groups. Thus, taking an active role in shaping people’s understanding of politics and social issues can positively influence their attitudes and political participation. The Constituent Constituents, or the general public, are often the numerical majority in social movements. They can include people who are sympathetic to but not committed to participating in actions for social change, or people who disagree with and resist social change messages. Unsurprisingly, constituents can greatly sway the progress of social movements, in that the attitudes and values they choose to adopt or reject influence the outcomes of state and federal elections, the types of laws and policies that governments and industries support, and broader norms in society. Thus, constituents have the power to elect leaders who support social change, call out unfair treatment and subvert anti-egalitarian norms, and support organisations and brands that make ethical choices (e.g. cruelty free cosmetics). Perhaps most importantly, other changes agents must make a considered effort to ensure that constituents have the information and support they need to make informed decisions and use their civic, relational, and economic powers effectively. Moving Forward Although the number and nature of these roles will likely vary between movements and socio-political contexts, they represent the diverse yet equally important forms of change agent work that can enhance the impact and effectiveness of social movements. The question now is: what role(s) do you play? How can you harness your unique skills and forms of influence to aid social change? Regardless of your answer, remember that just because you haven’t attended a protest or blocked oncoming traffic doesn’t mean that you aren’t a change agent. - By Morgana Lizzio-Wilson Disruptive protests gain media attention. For many people, this media attention might be the first time they learn of a particular social or environmental movement. his tactic and resulting media coverage often prompt predictable responses from the public and officials. Why, some ask, are protestors blocking roads instead of standing on the pavement educating people? Why protest if they don’t have a solution? But herein lurks a pervasive misconception of what activism actually is. Acts of civil disobedience enable awareness of a movement to bubble to the surface of daily life because they are newsworthy. However, this media attention can mask the years of relentless campaigning which builds the scaffolding to sustain these moments of shock. This scaffold is the groundwork done by the foot soldiers of a movement. Work done day after day, year after year, labouring at the often unseen toil that is the bread and butter of activism: recruiting volunteers, educating people and creating solutions. These tactics aren’t newsworthy. And sometimes to activists, they may feel like failure, creating the justification for the emergence of radical action. Does that mean that this toil was futile? Or, as argued by Extinction Rebellion, that tactics are now only just beginning? Coordinated acts of civil disobedience do not emerge spontaneously from an empty well. Take the American civil rights movement. Yes, Rosa Park’s determination to hold her bus seat created an iconic moment which helped galvanise the movement towards its goals. However, Rosa Parks was a long-term activist who, for decades, fought relentlessly against school segregation, wrongful convictions of black men, and anti-voter registration practices. Many other people had, in fact, held bus seats before her. She was one of thousands, many of whom, like her, were on the verge of exhaustion after perceiving that their years of activism had produced little change. We could look at any moment of newsworthy radical action and find parallels. Take the Salt March, an iconic moment of disobedience is now inextricably linked to the success of the Indian Independence movement. Organised as a defiant act against British rule in India, it was however, just one of the many tactics used in the 90 long years of struggle. Here in Australia, recent acts of civil disobedience for climate change action have emerged from a rich and vibrant foundation of environmentalism. Thousands of groups have been running thousands of campaigns across an array of issues. Activists have engaged in radical action against mining, logging and other destructive environmental practices for many years, using a diverse range of tactics for their cause. What were these tactics? Building groups, training volunteers, handing out flyers, organising workshops, visiting politicians, contacting polluting companies, developing policy frameworks. These tactics can successfully generate change. Almost half of the campaigns focussed on climate change achieved their goals, without the use of civil disobedience.

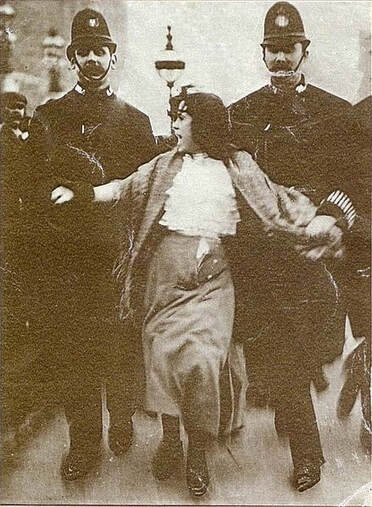

As social change researchers we look to understand the potential of tactics to generate change. But when we research activism, it is important to look beyond the headlines. Civil disobedience is not where ‘tactics begin’. As a movement works to raise awareness, create sympathy, motivate intentions to act, and ensure implementation, civil disobedience may instead be the end of the beginning. - By Robin Gulliver “Tell the truth and act as if the truth is real” – so goes the slogan of Extinction Rebellion (XR), a new international movement started in London in October 2018. The statement points to a discrepancy between the dire state of our environment and the lack of a real sense of emergency. While the majority of Australians’ understanding of the urgent need for action against climate change is reflected in their various every-day behaviours, there is still a lack of engagement in collective action for the environment. Despite the rise in individuals’ environmentally friendly behaviours, emissions continue to rise year after year. With 82% of all government subsidy still concentrated in ‘Clean Coal’, it’s clear that public policy still doesn't go far enough. While it might be more appealing to focus on improving our every-day behaviour as individuals, some argue that the pervasive messaging to get us to live our ‘best green life’ is actually a distraction designed to keep us content and away from collective action. However, there is a recent collective awakening about the need for systemic change over just changes in individual behaviour. These desperate times see the rise of more desperate measures of collective action such as non-violent civil resistance. Its practices and successes can be traced back to the Suffragettes, the American Civil Rights Movement, and LGBTQ movements. The specifics and strategies of civil resistance movements vary depending on their purpose and contextual factors. In this post, we’ll focus on civil resistance in the context of climate change action. The key principles remain similar across the movements:

Relevant audiences. Disruption is more effective in capital cities, as these are typically where national and international media are based. Just as labor strikes are effective against companies, closing down capital cities may be effective against governments. The inconvenience and disruption to the local populace and businesses is unavoidable. This can be harmful to the movement, so it’s important to inform the public about the urgency of the situation and the rationale behind the disruption. Prolonged disruption should be prewarned so emergency services can be rerouted.

Given the disruptive nature of civil resistance, public opinions can be quite divided. But if the sizes of the recent School Climate Strikes are anything to go by, the public’s appetite for drastic changes is growing rapidly, and this may come with corresponding greater support, or at least acceptance, of civil disobedience for climate change action. Environmental movements have to work to ensure that the political capital from mass mobilization for action isn’t wasted, as policy makers attempt to turn the conversation away from addressing climate change towards the law-breaking. Allies, policy makers, and the public have to be continually reminded that the story is about the science, the urgency of change, and the mass support for that change. Meanwhile, it’s up to the civil disobedience movements to galvanize support by informing the public about the movement’s rationale and considerations, and being inclusive of allies with varying political persuasions and beliefs. Regardless of whether you support civil disobedience or prefer more moderate activism, if there is a time to want more from our political system, the time is now. - Hannibal Thai The grass is not always greener in my neighbor’s garden… At least, that’s what people seem to think. In fact, when asked about others’ opinions toward sexual minorities’ issues, people tend to overestimate the level of intolerance in their society regardless of their personal views. In Switzerland, for example, residents thought that most other residents, including their neighbors, were intolerant toward same-sex marriage and same-sex parenting. Yet, this was not the case; Swiss residents were actually much more tolerant than what people thought (Eisner, Spini, & Sommet, 2019; Eisner, Turner-Zwinkels, Hässler, & Spini, 2019). You wouldn’t be surprised to hear that this perception of intolerance might impact on sexual and gender minorities’ well-being. To illustrate, perceptions of an intolerant climate toward sexual and gender minorities might raise expectations of rejection and, therefore, lead to concealment of one’s sexual orientation/gender identity and internalization of stigma. Moreover, perceptions of an intolerant climate might also affect social change processes themselves. Indeed, if you perceive that others in your society are intolerant of sexual and gender minorities, you might be discouraged from engaging in support for social change: “People aren’t ready for social change, thus, a social movement won’t be successful. So, let’s wait a little bit longer before pushing toward greater equality for sexual and gender minorities”. On the other hand, the intolerance you perceive might make you angry. This may lead you to believe that social change cannot be achieved without action: “This situation makes me so angry, we need to engage now because the situation is not getting better”. Hence, perceptions of intolerance could discourage or encourage support for social change. What did we do? While perceived climate might be relevant in all social movements, perception of others’ intolerance might particularly impact countries in which there are striking legal disparities. In Switzerland (and this might surprise you) sexual and gender minorities still suffer from many legal discriminations, such as being denied the right to marry and adopt. The legal discrimination goes so far that a single person can adopt a child, but as soon as you are in a registered same-sex partnership, you are not allowed to adopt children anymore. Importantly, while both sexual and gender minorities face many legal inequalities, the legal challenges of both groups are different. The present research was tailored to sexual minorities (e.g. homo-, bi-, pansexual people) since up-coming public voting regarding same-sex marriage affects sexual minorities. We tested the basic question of whether perceiving intolerant others discourages and/or encourages support for social change toward greater equality for sexual minorities in Switzerland. We gathered answers in our online questionnaire from sexual minorities (1220 participants) and cis-heterosexuals [1] (239 participants). What did we find? Perceiving others to be intolerant actually has a paradoxical impact on one’s support for social change:

What does this mean? Our research shows that the following detrimental effects of perception of an intolerant climate on support for social change must be key considerations when mobilizing for social change:

- Léïla Eisner & Tabea Hässler

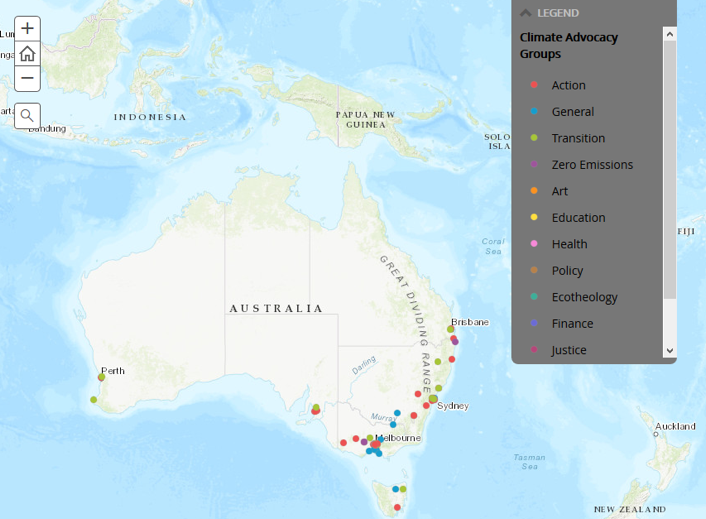

This blog post is based on: Eisner, L., Spini, D., & Sommet, N., (2019). A Contingent Perspective on Pluralistic Ignorance: When the Attitude Object Matters. International Journal of Public Opinion Research. https://doi.org/10.1093/ijpor/edz004 Eisner, L., Turner-Zwinkels, F., Hässler, T., & Spini, D., (2019). Pluralistic Ignorance of Societal Norms about Sexual Minorities. Manuscript under review; Eisner, L., Hässler, T., & Settersten, R. (2019). It’s time, act up for equality: Perceived societal norms and support for social change in the sexual minority context. Manuscript in preparation. [1] The term cis-heterosexuals denotes heterosexual individuals whose gender identity corresponds to their assigned sex. Who Runs The World? …Girls?: Why Female Leaders Struggle to Mobilise Individuals Toward Equality1/7/2019 Have you ever noticed that women are typically the ones spearheading gender equality movements? Think of the suffragettes, the #MeToo, and #TimesUp movements, the March for Women; All fronted by women – but at what cost? Research increasingly shows that relying solely on female leaders is not enough to achieve equality. Perhaps in response to this, there’s been a recent upsurge in male-led initiatives, such as the HeForShe movement, and the Male Champions of Change initiative. Both of these call on men to use their privilege and power to place gender equality on the agenda. These types of initiatives aren’t just companies taking a stab at something new – they’re backed by social psychological research. For example, two recent studies looking at how leader gender affected individuals’ responses to calls for equality found that men and women were more likely to follow a male leader into action (Hardacre & Subasic, 2018; Subasic et al., 2018). Importantly, the only change between the study conditions was the leader’s name and pronouns (e.g., from “Margaret” to “Matthew”). Below, we talk about some of the reasons why female leaders struggle to mobilise people toward equality. “Think manager, think male”: Leadership prototype embodies masculine attributes In our heads, we hold a 'prototype' of particular categories and roles – a fuzzy set of characteristics, attitudes, and behaviours that define certain groups and occupations. For example, if you were to think of a leader, you might think confident, assertive, and even male. Turns out this “think manager, think male” mindset is pervasive. Numerous leadership theories emphasise the desirability of stereotypically masculine traits in leaders. In fact, female leaders are frequently seen as ineffective because individuals’ ideas of effective leadership overlap with agentic male stereotypes (assertive, dominant), rather than communal female stereotypes (warm, nurturing). Even when female leaders do adopt masculine behaviours (such as those seen as typical of leaders), they face backlash because they’re seen as “violating” their traditional caring stereotype. This signifies a Catch-22 situation whereby female leaders are “damned if they do and doomed if they don’t!” Female leaders face accusations of self-interest, while male leaders are seen as having something to lose. It’s also difficult for female leaders of gender equality movements not to appear self-interested and overly invested in their cause (with good reason, given that it IS in their group’s best interests to challenge the status quo!). Essentially, women’s efforts at reducing inequality can be seen as furthering the interests of themselves and their group, and the more women are viewed as trying to benefit their own group, the more cynicism and dismissal they encounter. This can undermine women’s efforts at social change because acts of self-interest are less convincing and influential than acts that seem to oppose one’s best interests. In contrast, because many view gender equality as a zero-sum game, when men challenge gender inequality they’re seen as having something to lose – namely the rights and privilege that accompany their membership of a high-status group. This ultimately affords men greater legitimacy and influence, and therefore greater ability to mobilise followers. Male leaders possess a shared identity with men and women, while female leaders only share an identity with women. Possessing a shared identity with those you are trying to mobilise is at the crux of effective leadership, because those considered “us” are considered more influential than “them”. Herein lies another problem for female leaders. In gender equality contexts, male and female leaders both share a cause with women engaged in gender equality movements whilst men benefit from an additional shared social identity with men.. Meanwhile, no such shared identity yet exists for female leaders looking to mobilise a male audience. Instead, they’re seen as outgroup members by men in terms of their gender group membership, but also in terms of shared cause because gender equality is often seen as a women’s issue and of no benefit to men. Conclusion Paradoxically, by virtue of their gender and the privileges it permits, male leaders seem to have the ability to undertake gender equality leadership roles and mobilise men and women more effectively than female leaders. Research suggests that, among other reasons, this is due to leadership prototypes typically comprising masculine attributes, female leaders’ inability to escape accusations of self-interest, and male leaders’ possession of a shared identity with both male and female followers. It will be interesting to see how long the male ally advantage persists: in the longer term, effective feminist leadership will presumably eliminate the ironic inequality. - Guest post by Stephanie Hardacre (University of Newcastle). Activists are time and resource poor. They create social change by making quick decisions in stressful conditions, and often suffer disproportionately for their efforts. Given the urgency of our social and environmental challenges, linking activists with the latest research on topics ranging from how to engage in effective communication, to tactical decision making, to activist self-care, is more important than ever. Yet this research is mostly hidden behind paywalls or it is time consuming to acquire and apply. Thankfully, digital technologies offer a new opportunity to bridge the activist-researcher. Throughout my time here in the Social Change Lab, I’ve experimented with piloting effective research dissemination. This has lead me to the development of my website, www.earthactivists.com.au. This website began as a communication vehicle for various projects created during my time as a fellow in the University of Queensland Digital Research Fellowship program. The website is based on an initial dataset of 497 Australian environmental groups and 901 environmental campaigns. Mapped through the Esri ArcGIS online platform, the data and associated map will allow activists to easily view campaigns across all environmental issues, compare the data available on them, and track the campaign outcomes over time. Combined with archives collected on past environmental campaigns, one goal of the project is to create an open and accessible ‘treasure chest’ of information on Australia’s rich and diverse environmental movement. Open data can inform what type of activism is more likely to succeed; for example, data collected on over 100 years of protests demonstrates the surprising success rate of non-violent civil resistance as opposed to violence insurgencies. But it can also help enable stronger and more connected activists, reducing the ‘activist fatigue’ experienced through isolation and burnout. To this end, the website hosts stories of women fighting climate change. It also provides insights from experienced environmental campaigners on the highs and lows of activism, how they define success, and how they prioritise and acquire resources for their work. This website, still in its nascent stage, has been informed by international examples of accessible and open data on social change movements. One of the most influential of these examples is the Nonviolent and Violent Campaigns and Outcomes Data Project (NAVCO). This publically available dataset, initiated by Erica Chenoweth, has generated findings of international significance about the importance of non-violence civil resistance, and initiated a new research direction in civil resistance. Another successful open data initiative is that of the Environmental Justice Atlas (ejatlas.com). Centred on a global map of large scale environmental civil resistance campaigns, the project aims to both serve as a tool for informing activism and advocacy, and to foster increased academic research on the topic. Containing information on 2,100 environmental justice case studies, this project has international collaborators both contributing to new case studies and utilising existing studies for their activism and research. These examples demonstrate the new ways digital technology can be used as a bridge between activists and researchers. We have such a rich history of activists and activism around the globe. Collecting and sharing detailed empirical data about social and environmental collective action can help celebrate the work of those who fought for social and environmental justice in the past. But equally importantly, it can help inform how we can generate the urgent action we need to secure our future. In this time of crisis, bringing activists and researchers together is one more important than ever.

- Robyn Gulliver This blog post is the third summarising a special issue of PAC:JPP on the role of social movements in bringing about (or failing to bring about!) political and social transformation. I co-edited the special issue with Cristina Montiel, and it is available online to those with access (or by contacting the papers’ authors or via ResearchGate). Our intro summarising all articles is also online ‘open access’ here, along with the first two blog posts, dealing with tipping points or breakthroughs in conflict and the non-linear nature of social transformation and the wildly varying timescales. Some of these themes are also dealt with in a 2018 chapter by our group *. The overall aim of the special issue was to explore how social movements engage in, respond to, or challenge violence, both in terms of direct or physical violence and structural violence, injustice, and inequality. As well as the six papers summarised previously, there were four fascinating additional pieces by Montiel, Christie, Bretherton, and van Zomeren. Together the authors take up important questions about who acts, what changes, and how social transformation is achieved and researched, which I review below. Who can participate in the scholarship of transformation? Montiel’s (2018) piece “Peace Psychologists and Social Transformation: A Global South Perspective,” identifies barriers to full participation in the scholarship of peace. These barriers often include a relative lack of resources, and exposure to military, police, and non-state violence and trauma. In publishing, scholars and universities in the Global South face a difficult political environment in which both their silence and their speech may affect their careers and even their lives. More routinely, selection bias by journals to privilege the theoretical and methodological choices and agendas of the Global North marginalises the research questions that are most pressing, or most unfamiliar to WEIRD readers (Western, educated, industrialised, rich, democratic; Heinrich et al., 2010). In the short term, Montiel calls for professional bodies to open schemes for developing academics from the Global South; and for peace psychologists to co-design projects and conduct analyses and writing with southern scholars to allow a wider range of voices and ownership of the project. What is it that changes in social transformation? Van Zomeren’s (2018) piece “In search of a bigger picture: A cultural-relational perspective on social transformation and violence”, takes up his selvations theory as a springboard for understanding social transformation. He conceives the self as akin to a subjective vibration within a web of relationships (a selvation), which would both influence and be influenced by changing societies. Drawing on his earlier work on culture and collective action (e.g., van Zomeren & Louis, 2017), he suggests that the central challenge of the social psychology of social transformation is keeping the micro, meso, and macro-level variables in the same frame, and allowing emergent relationships within theoretical models. In the van Zomeren model, the decision-making self is embedded within relationships, with the regulation of those relationships a central goal of the actor. Thus relational norms for violence (or peace) become proximal predictors of change – which in turn rest on wider social norms and expectations of opponents’ actions (see also Blackwood & Louis, 2017). Violence may affirm or contradict the relationship models of the actors creating social change, which manifests as changing relationships with others: movement co-actors, targets, and the broader community. Christie and Bretherton, below, also echo the contention that it would be useful for scholars and practitioners to consider more deeply how social change involves changing relationships and the self. Five Components of Social Transformation Christie (2018) presents an analysis of effective social transformation movements, arguing that there are five components that campaigners and scholars must engage. A systemic approach is the foundation of social transformation, he proposes: transformation entails the creative construction and destruction of existing relationships and the development of more or less just and violent new ones. Sustainability is a second component: both the outcomes of a movement and its processes will last longer over time or less so. Momentary failures (and successes) are common; it is also the case that in the face of countervailing forces and counter-mobilisation, to sustain a positive status quo may require constant renewal and refreshment of social movement support. Third, a movement must also have the capacity to scale up, which often requires new skills, leadership, and institutional support – or more broadly, the ideological and organisational foundation to build new alliances and engage new topics and opportunities without compromising its values and direction. The fourth component of socially transformative movements is the inclusive involvement of those who are more powerless and marginalised: without active outreach and proactive inclusion, many movements re-invent old hierarchies and affirm old power structures. Finally, Christie closes with an interesting reflection on the metrics of social transformation, and the different conclusions that one might draw in mobilising to achieve greater lifespan, wealth, well-being, and/or cultural peace. Social Transformation: A How-To For Activists